William Bartram (1739-1823) was born on the Schuylkill River in Kingsessing, Pennsylvania, was the son of revered botanist John Bartram, and is often called America’s first native-born naturalist. William accompanied his father in 1765 on an expedition to East Florida, and with the support of the London physician John Fothergill, explored the present-day southeastern United States from 1773 to 1777. The latter, four-year journey became the basis for the book by which William Bartram is principally known: Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians (1791).

William Bartram (1739-1823) was born on the Schuylkill River in Kingsessing, Pennsylvania, was the son of revered botanist John Bartram, and is often called America’s first native-born naturalist. William accompanied his father in 1765 on an expedition to East Florida, and with the support of the London physician John Fothergill, explored the present-day southeastern United States from 1773 to 1777. The latter, four-year journey became the basis for the book by which William Bartram is principally known: Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians (1791).

Early reviews of Travels were mixed, and noted an appreciation for its scientific data but found fault with its effusive style. It has proven to be highly influential, however, and was read by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Henry David Thoreau, Francois de Chateaubriand, and others. Today the book stands as a standard reference on the natural history of the early United States, and is regarded as touchstone in the tradition of American environmental writing.

Edited by Gail Busjahn, University of South Florida St.Petersburg

Further Reading

Hallock, Thomas and Nancy E. Hoffmann (eds). William Bartram: The Search for Nature’s Design. Athens: U Georgia P, 2010. Print.

Harper, Frances The Travels of William Bartram Naturalist Edition.Athens. U Georgia P, 1998. Print.

McGee, Judith. The Art and Science of William Bartram. State College: Pennsylvania State U P, 2007. Print.

Slaughter, Thomas P. The Natures of John and William Bartram. New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 1996. Print.

William Bartram. Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians. Philadelphia: James and Johnson, 1791

Part Two: Chapter Five

Being desirous of continuing my travels and observations higher up the river and having an invitation from a gentleman who was an agent for and resident at a large plantation, the property of an English gentleman, about sixty miles higher up, I resolved to pursue my researches to that place. Having engaged in my service a young Indian, the nephew to the White Captain agreed to assist me in working my vessel up as high as a certain bluff where I was by agreement to land him on the west or Indian shore, whence he designed to go in quest of the camp of his relation, the White Trader.

Provisions and all necessaries being procured, and the morning pleasant, we went on board and stood up the river. We passed for several miles on the left, by islands of high swamp land that were exceedingly fertile, their banks for a good distance from the water, much higher than the interior part, and sufficiently so to build upon, and be out of the reach of inundations. They consist of a loose black mud, with a mixture of sand, shells and dissolved vegetables. The opposite Indian coast is a perpendicular bluff; ten or twelve feet high, consisting of a black sandy earth, mixed with a large proportion of shells, chiefly various species of fresh water Cochlea and Mytuli. Near the river, on this high shore, grew Corypha palma, Magnolia grandiflora, Live Oak, Callicarpa, Myrica cerifera, spinifex, and the beautiful evergreen shrub called Wild lime or Tallow nut. This last shrub grows six or eight feet high, many erect rising from a root; [115] the leaves are lanciolate and intire, two or three inches in length and one in breadth, of a deep green color, and polished. At the foot of each leaf grows a stiff, sharp thorn; the flowers are small and in clusters, of a greenish yellow color, and sweetly scented; they are succeeded by a large oval fruit, of the consistency and taste of an ordinary plumb, of a fine yellow color when ripe, a soft sweet pulp covers a nut which has a thin shell, enclosing a white kernel somewhat of the consistency and taste of the sweet almond, but more oily and very much like hard tallow, which induced my father when he first observed it, to call it the Tallow nut.

At the upper end of this bluff is a fine orange grove. Here my Indian companion requested me set him on shore. Being already tired of rowing under a fervid sun, and having for some time intimated a dislike to his situation, I readily complied with his desire, knowing the impossibility of compelling an Indian against his own inclinations, or even prevailing upon him by reasonable arguments when labor is in the question. Before my vessel reached the shore, he sprang out of her and landed. When uttering a thrill and terrible whoop, he bounded off like a roebuck, and I lost sight of him. I at first apprehended that as he took his gun with him, he intended to hunt for some game and return to me in the evening. The day being excessively hot and sultry, I concluded to take up my quarters here until next morning.

The Indian, not returning this morning, I sat sail alone. The coasts on each side had much the same appearance as already described. The palm trees here seem to be of a different species from the Cabbage tree; their strait trunks are sixty, eighty or ninety [116] feet high, with a beautiful taper of a bright ash color, until within six or seven feet of the top where it is a fine green color crowned with an orb of rich green plumed leaves. I have measured the stem of these plumes fifteen feet in length, besides the plume, which is nearly of the same length.

The little lake, which is an expansion of the river, now appeared in view; on the East side are extensive marshes, and on the other high forests and orange groves, and then a bay, lined with vast cypress swamps, both coasts gradually approaching each other, to the opening of the river again, which is in this place about three hundred yards wide. Evening now drawing on, I was anxious to reach some high bank of the river, where I intended to lodge, and agreeably to my wishes, I soon after discovered on the West shore, a little promontory, at the turning of the river, contracting it here to about one hundred and fifty yards in width. This promontory is a peninsula, containing about three acres of high ground and is one entire orange grove, with a few Live Oaks, Magnolias and palms. Upon doubling the point, I arrived at the landing, which is a circular harbor at the foot of the bluff, the top of which is about twelve feet high; the right wing forming the West coast of the little lake, and the left stretching up the river many miles, and encompassing a vast space of low grassy marshes. From this promontory, looking Eastward across the river we behold a landscape of low country, unparalleled as I think. On the left is the East coast of the little lake which I had just passed and from the orange bluff at the lower end the high forests begin, and increase in breadth from the shore of the lake, making [117] a circular sweep to the right, and contain many hundred thousand acres of meadow. This grand sweep of high forests encircles, as I apprehend, at least twenty miles of these green fields, interspersed with hommocks or islets of evergreen trees where the sovereign Magnolia and lordly palm stand conspicuous. The islets are high shelly knolls, on the sides of creeks or branches of the river which wind about and drain off the super-abundant waters that cover these meadows during the winter season.

The evening was temperately cool and calm. The crocodiles began to roar and appear in uncommon numbers along the shores and in the river. I fixed my camp in an open plain, near the utmost projection of the promontory, under the shelter of a large Live Oak, which stood on the highest part of the ground and but a few yards from my boat. From this open high situation, I had a free prospect of the river, which was a matter of no trivial consideration to me. Having good reason to dread the subtle attacks of the alligators, who were crowding about my harbor and having collected a good quantity of wood for the purpose of keeping up a light and smoke during the night, I began to think of preparing my supper. When upon examining my stores, I found but a scanty provision, I there upon determined, as the most expeditious way of supplying my necessities, to take my bob and try for some trout. About one hundred yards above my harbor, began a cove or bay of the river, out of which opened a large lagoon. The mouth or entrance from the river to it was narrow, but the waters soon after spread and formed a little lake extending into the marshes. Its entrance and shores within [118] I observed to be verged with floating lawns of the Pistia and Nymphea and other aquatic plants; these I knew were excellent haunts for trout.

The verges and islets of the lagoon were elegantly embellished with flowering plants and shrubs; the laughing coots with wings half spread were tripping over the little coves and hiding themselves in the tufts of grass. Young broods of the painted summer teal, skimming the still surface of the waters, and following the watchful parent unconscious of danger, were frequently surprised by the voracious trout, and he in turn, as often by the subtle, greedy alligator. Behold him rushing forth from the flags and reeds. His enormous body swells. His plaited tail brandished high, floats upon the lake. The waters like a cataract descend from his opening jaws. Clouds of smoke issue from his dilated nostrils. The earth trembles with his thunder. When immediately from the opposite coast of the lagoon, emerges from the deep his rival champion. They suddenly dart upon each other. The boiling surface of the lake marks their rapid course and a terrific conflict commences. They now sink to the bottom folded together in horrid wreaths. The water becomes thick and discolored. Again they rise, their jaws clap together, re-echoing through the deep surrounding forests. Again they sink when the contest ends at the muddy bottom of the lake, and the vanquished makes a hazardous escape, hiding himself in the muddy turbulent waters and sedge on a distant shore. The proud victor exulting, returns to the place of action. The shores and forests resound his dreadful roar, together with the triumphing shouts of the plaited tribes around, witnesses of the horrid combat. [119]

My apprehensions were highly alarmed after being a spectator of so dreadful a battle; it was obvious that every delay would but tend to increase my dangers and difficulties, as the sun was near setting, and the alligators gathered around my harbor from all quarters. From these considerations I concluded to be expeditious in my trip to the lagoon in order to take some fish. Not thinking it prudent to take my fusee with me, lest I might lose it overboard in case of a battle, which I had every reason to dread before my return, I therefore furnished myself with a club for my defense and went on board. Penetrating the first line of those that surrounded my harbor, they gave way. However, being pursued by several very large ones, I kept strictly on the watch, and paddled with all my might towards the entrance of the lagoon, hoping to be sheltered there from the multitude of my assailants. But ere I had halfway reached the place, I was attacked on all sides, several endeavoring to overset the canoe. My situation now became precarious to the last degree: two very large ones attacked me closely, at the same instant, rushing up with their heads and part of their bodies above the water, roaring terribly and belching floods of water over me. They struck their jaws together so close to my ears, as almost to stun me, and I expected every moment to be dragged out of the boat and instantly devoured, but I applied my weapons so effectually about me, though at random, that I was so successful as to beat them off a little; when, finding that they designed to renew the battle, I made for the shore. As the only means left me for my preservation, for, by keeping close to it, I should have my enemies on one side of me only, whereas I was before surrounded by them, and there was a probability, if pushed [120] to the last extremity, of saving myself, by jumping out of the canoe on shore, as it is easy to out-walk them on land, although comparatively as swift as lightning in the water. I found this last expedient alone could fully answer my expectations, for as soon as I gained the shore they drew off and kept aloof. This was a happy relief, as my confidence was, in some degree, recovered by it. On recollecting myself, I discovered that I had almost reached the entrance of the lagoon, and determined to venture in, if possible to take a few fish and then return to my harbor while day-light continued; for I could now, with caution and resolution, make my way with safety along shore. Indeed there was no other way to regain my camp without leaving my boat and making my retreat through the marshes and reeds, which if I could even effect, would have been in a manner throwing myself away, for then there would have been no hopes of ever recovering my bark, and returning in safety to any settlements of men. I accordingly proceeded and made good my entrance into the lagoon, though not without opposition from the alligators who formed a line across the entrance, but did not pursue me into it. Nor was I molested by any there, though there were some very large ones in a cove at the upper end. I soon caught more trout than I had present occasion for, and the air was too hot and sultry to admit of their being kept for many hours, even though salted or barbecued. I now prepared for my return to camp, which I succeeded in with but little trouble, by keeping close to the shore, yet I was opposed upon re-entering the river out of the lagoon, and pursued near to my landing (though not closely attacked) particularly by an old daring one, about twelve feet in length,[121] who kept close after me. When I stepped on shore and turned about, in order to draw up my canoe, he rushed up near my feet and lay there for some time. Looking me in the face, his head and shoulders out of water; I resolved he should pay for his temerity, and having a heavy load in my fusee, I ran to my camp, and returning with my piece, found him with his foot on the gunwale of the boat. In search of fish, on my coming up he withdrew sullenly and slowly into the water, but soon returned and placed himself in his former position looking at me and seeming neither fearful or any way disturbed. I soon dispatched him by lodging the contents of my gun in his head, and then proceeded to cleanse and prepare my fish for supper, and accordingly took them out of the boat, laid them down on the sand close to the water, and began to scale them, when, raising my head, I saw before me, through the clear water, the head and shoulders of a very large alligator, moving slowly towards me. I instantly stepped back, when with a sweep of his tail, he brushed off several of my fish. It was certainly most providential that I looked up at that instant, as the monster would probably, in less than a minute, have seized and dragged me into the river. This incredible boldness of the animal disturbed me greatly. Supposing there could now be no reasonable safety for me during the night, but by keeping continually on the watch; I therefore, as soon as I had prepared the fish, proceeded to secure myself and my effects in the best manner I could. In the first place, I hauled my bark upon the shore, almost clear out of the water, to prevent their oversetting or sinking. After this, every moveable was taken out and carried to my camp, [122] which was but a few yards off. Then arranging some dry wood in such order as was the most convenient, I cleared the ground round about it, that there might be no impediment in my way, in case of an attack in the night, either from the water or the land. For I discovered by this time, that this small isthmus, from its remote situation and fruitfulness, was resorted to by bears and wolves. Having prepared myself in the best manner I could, I charged my gun and proceeded to reconnoiter my camp and the adjacent grounds; when I discovered that the peninsula and grove, at the distance of about two hundred yards from my encampment, on the land side, were invested by a cypress swamp. Covered with water, which below was jointed to the shore of the little lake, and above to the marshes surrounding the lagoon so that I was confined to an islet exceedingly circumscribed, and I found there was no other retreat for me, in case of an attack, but by either ascending one of the large oaks, or pushing off with my boat.

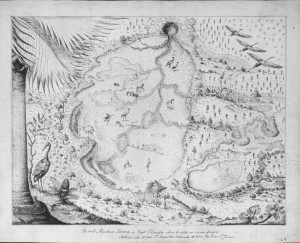

It was by this time dusk and the alligators had nearly ceased their roar, when I was again alarmed by a tumultuous noise that seemed to be in my harbor, and therefore engaged my immediate attention. Returning to my camp I found it undisturbed, and then continued on to the extreme point of the promontory, where I saw a scene, new and surprising, which at first threw my senses into such a tumult that it was some time before I could comprehend what was the matter. However, I soon accounted for the prodigious assemblage of crocodiles at this place, which exceeded every thing of the kind I had ever heard of.

How shall I express myself so as to convey an [123] adequate idea of it to the reader, and at the same time avoid raising suspicions of my want of veracity? Should I say, that the river (in this place) from shore to shore, and perhaps near half a mile above and below me, appeared to be one solid bank of fish of various kinds pushing through this narrow pass of St. Juans into the little lake? On their return down the river the alligators were in such incredible numbers, and so close together from shore to shore, that it would have been easy to have walked across on their heads, had the animals been harmless. What expressions can sufficiently declare the shocking scene that for some minutes continued, whilst this mighty army of fish were forcing the pass? During this attempt, thousands, I may say hundreds of thousands of them were caught and swallowed by the devouring alligators. I have seen an alligator take up out of the water several great fish at a time, and just squeeze them betwixt his jaws, while the tails of the great trout flapped about his eyes and lips, ere he had swallowed them. The horrid noise of their closing jaws, their plunging amidst the broken banks of fish, and rising with their prey some feet upright above the water; the floods of water and blood rushing out of their mouths, and the clouds of vapor issuing from their wide nostrils, were truly frightful. This scene continued at intervals during the night, as the fish came to the pass. After this sight, shocking and tremendous as it was, I found myself somewhat easier and more reconciled to my situation, being convinced that their extraordinary assemblage here, was owing to this annual feast of fish, and that they were so well employed in their own element, that I had little occasion to fear their paying me a visit. [124]

It being now almost night, I returned to my camp, where I had left my fish broiling and my kettle of rice stewing, and having with me, oil, pepper and salt, and excellent oranges hanging in abundance over my head (a valuable substitute for vinegar) I sat down and regaled myself cheerfully. Having finished my repast, I re-kindled my fire for light, and whilst I was revising the notes of my past day’s journey, I was suddenly roused with a noise behind me toward the main land; I sprang up on my feet, and listening, I distinctly heard some creature wading in the water of the isthmus. I seized my gun and went cautiously from my camp, directing my steps towards the noise. When I had advanced about thirty yards, I halted behind a coppice of orange trees, and soon perceived two very large bears which had made their way through the water, and had landed in the grove about one hundred yards distance from me and were advancing towards me. I waited until they were within thirty yards of me; they there began to snuff and look towards my camp. I snapped my piece, but it flashed on which they both turned about and galloped off plunging through the water and swamp, never halting as I suppose, until they reached fast land. As I could hear them leaping and plunging a long time, they did not presume to return again, nor was I molested by any other creature, except being occasionally awakened by the whooping of owls, screaming of bitterns, or the wood-rats running amongst the leaves.

The wood-rat is a very curious animal. They are not half the size of the domestic rat, are of a dark brown or black color, their tail slender and shorter in proportion, and covered thinly with short hair. They are [125] singular with respect to their ingenuity and great labor in the construction of their habitations, which are conical pyramids about three or four feet high, constructed with dry branches which they collect with great labor and perseverance and pile up without any apparent order; yet they are so interwoven with one another, that it would take a bear or wild-cat some time to pull one of these castles to pieces, and allow the animals sufficient time to secure a retreat with their young.

The noise of the crocodiles kept me awake the greater part of the night. When I arose in the morning, contrary to my expectations, there was perfect peace. Very few of them were to be seen, and those that were, were asleep on the shore, yet I was not able to suppress my fears and apprehensions of being attacked by them in the future. Indeed yesterday’s combat with them, notwithstanding, I came off in a manner victorious, or at least made a safe retreat, and it had left a sufficient impression on my mind to dampen my courage. It seemed too much for one of my strength, being alone in a very small boat, to encounter such collected danger. To pursue my voyage up the river and be obliged every evening to pass such dangerous defiles, appeared to me as perilous as running the gauntlet betwixt two rows of Indians armed with knives and fire brands. I however resolved to continue my voyage one day longer, if I possibly could with safety, and then return down the river, should I find the like difficulties to oppose. Accordingly I got everything on board, charged my gun, and set sail cautiously along shore. As I passed by Battle Lagoon, I began to tremble and keep a good look out, when suddenly a huge alligator rushed out of the reeds, and [126] with a tremendous roar, came up, and darted as swift as an arrow under my boat. Emerging upright on my lea quarter, with open jaws, and belching water and smoke that fell upon me like rain in a hurricane, I laid soundly about his head with my club and beat him off. After plunging and darting about my boat, he went off on a strait line through the water, seemingly with the rapidity of lightning, and entered the cape of the lagoon. I now employed my time to the very best advantage in paddling close along shore, but could not forbear looking now and then behind me, and presently perceived one of them coming up again; the water of the river hereabouts, was shoal and very clear. The monster came up with the usual roar and menaces and passed close by the side of my boat when I could distinctly see a young brood of alligators to the number of one hundred or more following after her in a long train. They kept close together in a column without straggling off to the one side or the other. The young appeared to be of an equal size, about fifteen inches in length, almost black, with pale yellow transverse waved clouds or blotches, much like rattle snakes in color. I now lost sight of my enemy again.

Still keeping close along shore on turning a point or projection of the riverbank, at once I beheld a great number of hillocks or small pyramids resembling haycocks, ranged like an encampment along the banks. They stood fifteen or twenty yards distance from the water on a high marsh about four feet perpendicular above the water. I knew them to be the nests of the crocodile, having had a description of them before, and now expected a furious and general attack, as I saw several large crocodiles [127] swimming abreast of these buildings. These nests being so great a curiosity to me, I was determined at all events immediately to land and examine them. Accordingly I ran my bark on shore at one of their landing places, which was a sort of nick or little dock from which ascended a sloping path or road up to the edge of the meadow where their nests were. Most of them were deserted, and the great thick whitish egg-shells lay broken and scattered upon the ground round about them.

The nests or hillocks are of the form of an obtuse cone, four feet high and four or five feet in diameter at their bases. They are constructed with mud, grass and herbage. At first they lay a floor of this kind of tempered mortar on the ground, upon which they deposit a layer of eggs, and upon this a stratum of mortar seven or eight inches in thickness, and then another layer of eggs, and in this manner one stratum upon another, nearly to the top. I believe they commonly lay from one to two hundred eggs in a nest; these are hatched I suppose by the heat of the sun, and perhaps the vegetable substances mixed with the earth, being acted upon by the sun, may cause a small degree of fermentation, and so increase the heat in those hillocks. The ground for several acres about these nests showed evident marks of a continual resort of alligators. The grass was everywhere beaten down, hardly a blade or straw was left standing; whereas, all about at a distance, it was five or six feet high and as thick as it could grow together. The female, as I imagine, carefully watches her own nest of eggs until they are all hatched, or perhaps while she is attending her own brood, she takes under her care and protection, as many as the can get at one time, either [128] from her own particular nest or others. But certain it is, the young are not left to shift for themselves. Having had frequent opportunities of seeing the female alligator leading about the shores her train of young ones just like a hen does her brood of chickens; she is equally assiduous and courageous in defending the young, which are under her care providing for their subsistence. When the alligator is basking upon the warm banks with her brood around her, you may hear the young ones continually whining and barking, like young puppies. I believe but few of a brood live to the years of full growth and magnitude, as the old feed on the young as long as they can make prey of them.

The alligator when full grown is a very large and terrible creature of prodigious strength, activity and swiftness in the water. I have seen them twenty feet in length, and some are supposed to be twenty-two or twenty-three feet. Their body is as large as that of a horse; their shape exactly resembles that of a lizard, except their tail which is flat or uniform, being compressed on each side, and gradually diminishing from the abdomen to the extremity. The whole body is covered with horny plates or squammae, impenetrable when on the body of the live animal, even to a rifle ball, except about their head and just behind their fore-legs or arms, where it is said they are only vulnerable. The head of a full grown one is about three feet and the mouth opens nearly the fame length. The eyes are small in proportion and seem sunk deep in the head by means of the prominence of the brows. The nostrils are large, inflated and prominent on the top so that the head in the water resembles, at a distance, a great [129] chunk of wood floating about. Only the upper jaw moves, which they raise almost perpendicular, so as to form a right angle with the lower one. In the fore part of the upper jaw, on each side, just under the nostrils, are two very large, thick, strong teeth or tusks, not very sharp, but rather the shape of a cone. These are as white as the finest polished ivory and are not covered by any skin or lips, and always in sight, which gives the creature a frightful appearance. In the lower jaw are holes opposite to these teeth to receive them; when they clap their jaws together it causes a surprising noise, like that which is made by forcing a heavy plank with violence upon the ground, and may be heard at a great distance.

But what is yet more surprising to a stranger, is the incredible loud and terrifying roar, which they are capable of making, especially in the spring season, their breeding time; it most resembles very heavy distant thunder, not only shaking the air and waters, but causing the earth to tremble. When hundreds and thousands are roaring at the same time, you can scarcely be persuaded, but that the whole globe is violently and dangerously agitated.

An old champion who is perhaps absolute sovereign of a little lake or lagoon (when fifty less than himself are obliged to content themselves with swelling and roaring in little coves round about) darts forth from the reedy coverts all at once on the surface of the waters in a right line; at first seemingly as rapid as lightning, but gradually more slowly until he arrives at the center of the lake, when he stops now swells himself by drawing in wind and water through his mouth, which causes a loud [130] sonorous rattling in the throat for near a minute, but it is immediately forced out again through his mouth and nostrils, with a loud noise, brandishing his tail in the air, and the vapor ascending from his nostrils like smoke. At other times, when swollen to an extent ready to burst, his head and tail lifted up, he spins or twirls round on the surface of the water. He acts his part like an Indian chief when rehearsing his feats of war, and then retiring, the exhibition is continued by others who dare to step forth, and strive to excel each other, to gain the attention of the favorite female.

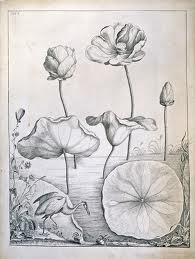

Having gratified my curiosity at this general breeding place and nursery of crocodiles, I continued my voyage up the river without being greatly disturbed by them. In my way I observed islets or floating fields of the bright green Pistia, decorated with other amphibious plants, as Senecio Jacobea, Persicaria amphibia, Coreopsis bidens, Hydrocotile fluitans, and many others of less note.

The swamps on the banks and island of the river are generally three or four feet above the surface of the water, and very level. The timber large and growing thinly more so than what is observed to be in the swamps below Lake George; the black rich earth is covered with moderately tall, and very succulent tender grass, which when chewed is sweet and agreeable to the taste, some what like young sugarcane. It is a jointed decumbent grass, sending out radiculae at the joints into the earth, and so spreads itself, by creeping over its surface.

The large timber trees, which possess the low lands, are Acer rubrum, Ac. nigundo, Ac. glaucum, Ulmus sylvatica, Fraxinus excelsior, Frax. aquatica, Ulmus [131] suberifer, Gleditsia monosperma, Gledit. triacanthus, Diospyros Virginica, Nyssa aquatica, Nyssa sylvatica, Juglans cinerea, Quercus dentata, Quercus phillos, Hopea tinctoria, Corypha palma, Morus rubra, and many more. The Palm grows on the edges of the banks, where they are raised higher than the adjacent level ground by the accumulation of sand, river-shells, &c. I passed along several miles by those rich swamps, the channels of the river, which encircle the several fertile islands I had passed, now uniting, formed one deep channel near three hundred yards over. The banks of the river on each side began to rise and present shelly bluffs, adorned by beautiful orange groves, laurels and Live Oaks. And now appeared in sight, a tree that claimed my whole attention: it was the Carica Papaya, both male and female, which were in flower, and the latter both in flower and fruit, some of which were ripe, as large and of the form of a pear and of a most charming appearance.

This admirable tree is certainly the most beautiful of any vegetable production I know of; the towering Laurel Magnolia, and exalted Palm, indeed exceed it in grandeur and magnificence, but not in elegance, delicacy and gracefulness. It rises erect, with a perfectly strait tapering them to the height of fifteen or twenty feet, which is smooth and polished, of a bright ash color, resembling leaf silver, curiously inscribed with the footsteps of the fallen leaves, and these vestiges, are placed in a very regular uniform imbricated order, which has a fine effect, as if the little column were elegantly carved all over. Its perfectly spherical top is formed of very large lobe-sinuate leaves supported on very long footstalks. The lower leaves are the largest as well as their petioles the longest, and make [132]a graceful sweep or flourish, like the long S on the branches of a sconce candlestick. The ripe and green fruit are placed round about the stem or trunk, from the lowermost leaves where the ripe fruit are. Upwards almost to the top the heart or inmost pithy part of the trunks is in a manner hollow, or at best consists of very thin porous medullae or membranes. The tree very seldom branches or divides into limbs, I believe never unless the top is by accident broken off when very young. I saw one, which had two tops or heads, the stem of which divided near the earth. It is always green, ornamented at the same time with flowers and fruit, which like figs come out singly from the trunk or stem.

After resting and refreshing myself in these delightful shades, I left them with reluctance, embarking again after the fervid heats of the meridian sun were abated. For some time I passed by broken ridges of shelly high land, covered with groves of Live Oak, palm, Olea Americana, and orange trees; frequently observing floating islets and green fields of the Pistia near the shores of the river and lagoons.

Here is in this river and in the waters all over Florida, a very curious and handsome bird, the people call them Snake Birds. I think I have seen paintings of them on the Chinese screens and other India pictures. They seem to be a species of cormorant or loon (Colymbus cauda elongata) but far more beautiful and delicately formed than any other species that I have ever seen. The head and neck of this bird are extremely small and slender, the latter very long indeed, almost out of all proportion. The bill long, strait and slender, tapering [133] from its ball to a sharp point, all the upper side, the abdomen and thighs, are as black and glossy as a raven’s, covered with feathers so firm and elastic, that they in some degree resemble fish-scales. The breast and upper part of the belly are covered with feathers of a cream color. The tail is very long, of a deep black, and tipped with a silvery white, and when spread, represent an unfurled fan. They delight to sit in little peaceable communities on the dry limbs of trees, hanging over the still waters, with their wings and tails expanded. I suppose to cool and air themselves, when at the same time they behold their images in the watery mirror; at such times, when we approach them, they drop off the limbs into the water as if dead, and for a minute or two are not to be seen; when on a sudden at a vast distance, their long slender head and neck only appear, and have very much the appearance of a snake, and no other part of them are to be seen when swimming in the water, except some the tip end of their tail. In the heat of the day they are seen in great numbers, sailing very high in the air, over lakes and rivers.

I doubt not but if this bird had been an inhabitant of the Tiber in Ovid’s days, it would have furnished him with a subject, for some beautiful and entertaining metamorphoses. I believe they feed entirely on fish, for their flesh smells and tastes intolerably strong of it. It is scarcely to be eaten unless constrained by insufferable hunger.

I had now swamps and marshes on both sides of me, and evening coming on a pace, I began to look out for high land to camp on, but the extensive marshes seemed to have no bounds; and it was almost dark when I found a tolerable suitable place, [134] and at last was constrained to take up on a narrow strip of high shelly bank, on the West side. Great numbers of crocodiles were in sight on both shores. I ran my boat on shore at a perpendicular bank four or five feet above the water, just by the roots and under the spreading limbs of a great Live Oak. This appeared to have been an ancient camping place by Indians and strolling adventurers, from ash heaps and old rotten fire brands, and chunks, scattered about on the surface of the ground; but was now evidently the harbor and landing place of some sovereign alligator; there led up from it a deep beaten path or road, and was a convenient ascent.

I did not approve of my intended habitation from these circumstances; and no sooner had I landed and moored my canoe to the roots of the tree, than I saw a huge crocodile rising up from the bottom close by me, who, when he perceived that I saw him, plunged down again under my vessel. This determined me to be on my guard, and in time to provide against a troublesome night, I took out of my boat every moveable, which I carried upon the bank, then chose my lodging close to my canoe, under the spreading oak; as hereabouts only, the ground was open and clear of high grass and bushes, and consequently I had some room to stir and look round about. I then proceeded to collect firewood, which I found difficult to procure. Here were standing a few orange trees. As for provisions, I had saved one or two barbecued trout, the remains of my last evening’s collection in tolerable good order.

Though the sultry heats of the day had injured them; yet by stewing them up afresh with the lively juice of oranges, they served well enough for my supper. Having by this time but little relish or appetite [135] for my victuals; for constant watching at night against the attacks of alligators, stinging of mosquitoes and sultry heats of the day; together, with the fatigues of working my bark, had almost deprived me of every desire but that of ending my troubles as speedy as possible. I had the good fortune to collect together a sufficiency of dry sticks to keep up a light and smoke, which I laid by me, and then spread my skins and blankets upon the ground, kindled up a little fire and supped before it was quite dark. The evening was however, extremely pleasant, a brisk cool breeze sprang up, and the skies were perfectly serene, the stars twinkling with uncommon brilliancy. I stretched myself along before my fire. Having the river, my little harbor and the stern of my vessel in view, and now through fatigue and weariness I fell asleep. But this happy temporary release from cares and troubles I enjoyed but a few moments, when I was awakened and greatly surprised, by the terrifying screams of Owls in the deep swamps around me. What increased my extreme misery was the difficulty of getting quite awake, and yet hearing at the same time such screaming and shouting, which increased and spread every way for miles around, in dreadful peals vibrating through the dark extensive forests, meadows and lakes. I could not after this surprise recover the former peaceable state and tranquility of mind and repose, during the long night, and I believe it was happy for me that I was awakened, for at that moment the crocodile was dashing my canoe against roots of the tree, endeavoring to get into her for the fish, which I however prevented. Another time in the night I believe I narrowly escaped being dragged into the river by him, for when again through excessive fatigue I had fallen [136] asleep, but was again awakened by the screaming owl, I found the monster on the top of the bank, his head towards me not above two yards distant, when starting up and seizing my fuzee well loaded, which I always kept under my head in the night time, he drew back and plunged into the water. After this I roused up my fire, and kept a light during the remaining part of the night. Being determined not to be caught napping so again, indeed the mosquitoes alone would have been abundantly sufficient to keep any creature awake that possessed their perfect senses, but I was overcome, and stupefied with incessant watching and labor. As soon as I discovered the first signs of day-light, I arose, got all my effects and implements on board and set sail. Proceeding upwards, hoping to give the mosquitoes the slip, who were now, by the cool morning dews and breezes, driven to their shelter and hiding places; I was mistaken however in these conjectures, for great numbers of them, which had concealed themselves in my boat, as soon as the sun arose, began to revive, and sting me on my legs which obliged me to land in order to get bushes to beat them out of their quarters.

It is very pleasing to observe the banks of the river ornamented w ith hanging garlands, composed of varieties of climbing vegetables, both shrubs and plants, forming perpendicular green walls, with projecting jambs, pilasters and deep apartments, twenty or thirty feet high and compleatly covered, with Glycine frutescens, Glyc. apios, Vitis labrusca, Vitis vulpina, Rajana, Hedera quinquifolia, Hedera arborea, Eupatorium scandens, Bignonia crucigera, and various species of Convolvulus, particularly an amazing tall climber of this [137] genus, or perhaps an Ipomea. This has a very large white flower, as big as a small funnel, its tube is five or six inches in length and not thicker than a pipe stem. The leaves are also very large, oblong and chordate, sometimes dentate or angled, near the insertion of the foot-stalk. They are of a thin texture, and of a deep green color. It is exceedingly curious to behold the Wild Squash[1] climbing over the lofty limbs of the trees, their yellow fruit somewhat of the size and figure of a large orange, pendant from the extremities of the limbs over the water.

ith hanging garlands, composed of varieties of climbing vegetables, both shrubs and plants, forming perpendicular green walls, with projecting jambs, pilasters and deep apartments, twenty or thirty feet high and compleatly covered, with Glycine frutescens, Glyc. apios, Vitis labrusca, Vitis vulpina, Rajana, Hedera quinquifolia, Hedera arborea, Eupatorium scandens, Bignonia crucigera, and various species of Convolvulus, particularly an amazing tall climber of this [137] genus, or perhaps an Ipomea. This has a very large white flower, as big as a small funnel, its tube is five or six inches in length and not thicker than a pipe stem. The leaves are also very large, oblong and chordate, sometimes dentate or angled, near the insertion of the foot-stalk. They are of a thin texture, and of a deep green color. It is exceedingly curious to behold the Wild Squash[1] climbing over the lofty limbs of the trees, their yellow fruit somewhat of the size and figure of a large orange, pendant from the extremities of the limbs over the water.

Towards noon, the sultry heat being intolerable, I put into shore at a middling high bank five or six feet above the surface of the river. This low sandy testaceous ridge along the river side was but narrow, the surface light, black and exceedingly fertile, producing very large venerable Live Oaks, Palms and grand Magnolias, scattered and planted by nature. There being no underwood to prevent the play of the breezes from the river, afforded a desirable retreat from the sun’s heat; immediately back of this narrow ridge, was deep wet swamps, where stood some astonishingly tall and spreading Cypress trees; and now being weary and drowsy, I was induced to indulge and listen to the dictates of reason and invitations to repose, which consenting to, after securing my boat and reconnoitering the ground, I spread my blanket under the oaks near my boat, on which I extended myself, where falling to sleep, I instantaneously passed away the sultry hours of noon. What a blissful tranquil repose! Undisturbed I awoke, refreshed and strengthened; I cheerfully stepped on board again and continued to ascend the river. [138]

…. I put in at an ancient landing place, which is a sloping ascent to a level grassy plain, an old Indian field. As I intended to make my most considerable collections at this place, I proceeded immediately to fix my encampment but a few yards from my safe harbor, where I securely fastened my boat to a Live Oak which overshadowed my port.

After collecting a good quantity of firewood, as it was about the middle of the afternoon, I resolved to reconnoiter the ground about my encampment. Having penetrated the groves next to me, I came to the open forests, consisting of exceedingly [161] tall strait Pines (Pinus Palustris) that stood at a considerable distance from each other, through which appeared at N. W. an almost unlimited plain of grassy savannas, embellished with a chain of shallow ponds, as far as the sight could reach. Here is a species of Magnolia that associates with the Gordonia lasianthus; it is a tall tree, sixty or eighty feet in height. The trunk is strait, its head terminating in the form of a sharp cone, the leaves are oblong, lanciolate, of a fine deep green, and glaucous beneath; the flowers are large, perfectly white and extremely fragrant. With respect to its flowers and leaves, it differs very little from the Magnolia glauca. The silvery whiteness of the leaves of this tree, had a striking and pleasing effect on the sight, as it stood amidst the dark green of the Quercus dentata, Nyssa sylvatica, Nys. aquatica, Gordonia lasianthus and many others of the same hue. The tall aspiring Gordonia Lasianthus, which now stood in my view in all its splendor, is every way deserving of our admiration. Its thick foliage, of a dark green color, is flowered over with large milk-white fragrant blossoms, on long slender elastic peduncles, at the extremities of its numerous branches, from the bosom of the leaves, and renewed every morning; and that in such incredible profusion, that the tree appears silvered over with them, and the ground beneath covered with the fallen flowers. It at the same time continually pushes forth new twigs, with young buds on them and in the winter and spring the third year’s leaves, now partly concealed by the new and perfect ones, are gradually changing color, from green to golden yellow, from that to a scarlet, from scarlet to crimson, and lastly to a brownish purple, and then fall [162] to the ground. So that the Gordonia Lasianthus may be said to change and renew its garments every morning throughout the year and every day appears with unfading luster. And moreover, after the general flowering is past, there is a thin succession of scattering blossoms to be seen on some parts of the tree, almost every day throughout the remaining months until the floral season returns again. Its natural situation when growing is on the edges of shallow ponds, or low wet grounds on rivers, in a sandy soil. The nearest to the water of any other tree, so that in drought seasons its long serpentine roots which run near or upon the surface of the earth, may reach into the water. When the tree has arrived to the period of perfect magnitude, it is sixty, eighty or a hundred feet high, forming a pyramidal head. The wood of old trees when sawn into plank, is deservedly admired in cabinet-work or furniture. It has a cinnamon colored ground, marbled and veined with many colors; the inner bark is used for dying a reddish or sorrel color. It imparts this color to wool, cotton, linen and dressed deer skins, and is highly esteemed by tanners.

The Zamia pumila, the Erythryna corallodendrum and the Cactus opuntia grow here in great abundance and perfection. The first grows in the open pine forests, in tufts or clumps; a large conical strobili disclosing its large coral red fruit, which appears singularly beautiful amidst the deep green fern-like pinnate leaves. The Erythryna Corallodendrum is six or eight feet high; its prickly limbs stride and wreathe about with singular freedom, and its spikes of crimson flowers have a fine effect amidst the delicate foliage. [163] The Cactus Opuntia is very tall, erect and large, and strong enough to bear the weight of a man. Some are seven or eight feet high. The whole plant or tree seems to be formed of great oval compressed leaves or articulations. Those near the earth continually increase, magnify and indurate as the tree advances in years, and at length lose the bright green color and glossy surface of their youth, acquiring a ligneous quality, with a whitish scabrous cortex. Every part of the plant is nearly destitute of aculeate, or those fascicles of barbed bristles, which are in such plenty on the common, dwarf Indian Fig. The Cochineal insect were feeding on the leaves. The female of this insect is very large and fleshy, covered with a fine white silk or cottony web, which feels always moist or dewy, and seems designed by nature to protect them from the violent heat of the sun. The male is very small in comparison to the female, and are very few in number. They each have two oblong pellucid wings. The large polypetalous flowers are produced on the edges of the last year’s leaves, are of a fine splendid yellow, and are succeeded by very large pear shaped fruit of a dark livid purple when ripe. Its pulp is charged with a juice of a fine transparent crimson color, and has a cool pleasant taste, somewhat like that of a pomegranate. Soon after eating this fruit urine becomes of the same crimson color, which very much surprises and affrights a stranger, but is attended with no other ill consequence. On the contrary, it is esteemed wholesome, though powerfully diuretic.

On the left hand of those open forests and savannas, as we turn our eyes Southward, South-west and West, we behold an endless wild desert, the upper stratum of the earth of which is a fine white sand, with small pebbles, and at some distance appears entirely covered with low trees and shrubs of [164] various kinds, and of equal height, as dwarf Sweet Bay (Laurus Borbonia) Olea Americana, Morus rubra, Myrica cerifera, Ptelea, Æsculus pavia, Quercus Ilex, Q. glandifer, Q. maritima, foliis obcunciformibus obsolete tribobis minoribus, Q. pumila, Rhamnus frangula, Halesia diptera, & Tetraptera, Cassine, Ilex aquifolium, Callicarpa Johnsonia, Erythryna corallodendrum, Hibiscus spinifex, Zanthoxilon, Hopea tinctoria, Sideroxilum, with a multitude of other shrubs, many of which are new to me, and some of them admirably beautiful and singular. One of them particularly engaged my notice, which, from its fructification I take to be a species of Cacalia. It is an evergreen shrub, about six or eight feet high, the leaves are generally somewhat uniform, fleshly and of a pale whitish green, both surfaces being covered with a hoary pubescence and vesicular, that when pressed feels clammy, and emits an agreeable scent. The ascendant branches terminate with large tufts or corymbs of rose-colored flowers, of the same agreeable scent. These cluster of flowers, at a distance, look like a large Carnation or fringed Poppy flower (Syngenesia Polyg. Oqul. Linn.) Cacalia heterophylla, foliis cuniformibus, carnosis, papil. viscidis.

Here is also another species of the same genus, but it does not grow quite so large; the leaves are smaller, of a yet duller green color, and the flowers are of a pale rose; they are both valuable evergreens. The trees and shrubs which cover these extensive wilds, are about five or six feet high, and seem to be kept down by the annual firing of the deserts, rather than the barrenness of the soil, as I saw a few large Live Oaks, Mulberry trees and Hickories, [165] which evidently have withstood the devouring flames. These adjoining wild plains, forests and savannas, are situated lower than the hilly groves on the banks of the lake and river, but what should be the natural cause of it I cannot even pretend to conjecture, unless one may suppose that those high hills, which we call bluffs, on the banks of this great river and its lakes, and which support those magnificent groves and high forests, and are generally composed of shell and sand, were thrown up to their present height by the winds and waves, when the bed of the river was nearer the level of the present surface of the earth; but then, to rest upon such a supposition, would be admitting that the waters were heretofore in greater quantities than at this time, or that their present channels and receptacles are worn deeper into the earth.

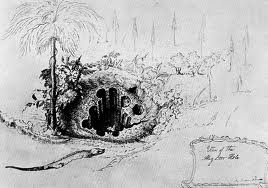

I now directed my steps towards my encampment, in a different direction. I seated myself upon a swelling green knoll, at the head of the crystal basin. Near me, on the left, was a point or projection of an entire grove of the aromatic Illisium Floridanum. On my right and all around behind me, was a fruitful orange grove, with Palms and Magnolias interspersed in front. Just under my feet was the enchanting and amazing crystal fountain, which incessantly threw up, from dark, rocky caverns below, tons of water every minute, forming a basin, capacious enough for large shallops to ride in, and a creek of four or five feet depth of water, and near twenty yards over, which meanders six miles through green meadows, pouring its limpid waters into the great Lake George, where they seem to remain pure and unmixed. About twenty yards from the upper edge of the basin,[166] and directly opposite to the mouth or outlet to the creek, is a continual and amazing ebullition, where the waters are thrown up in such abundance and amazing force, as to jet and swell up two or three feet above the common surface. White sand and small particles of shells are thrown up with the waters, near to the top, when they diverge from the center, subside with the expanding flood, and gently sink again, forming a large rim or funnel round about the aperture or mouth of the fountain, which is a vast perforation through a bed of rocks, the ragged points of which are projected out on every side. Thus far I know to be matter of real fact, and I have related it as near as I could conceive or express myself. But there are yet remaining scenes inexpressibly admirable and pleasing.

Behold, for instance, a vast circular expanse before you, the waters of which are so extremely clear as to be absolutely diaphanous or transparent as the ether. The margin of the basin ornamented with a great variety of fruitful and floriferous trees, shrub and plants, the pendant golden orange dancing on the surface of the pellucid waters, the balmy air vibrates the melody of the merry birds, tenants of the encircling aromatic grove.

At the same instant innumerable bands of fish are seen, some clothed in the most brilliant colors; the voracious crocodile stretched along at full length, as the great trunk of a tree in size, the devouring garfish, inimical trout, and all the varieties of gilded painted bream, the barbed catfish, dreaded sting-ray, skate and flounder, spotted bass, sheep’s head and ominous drum; all in their separate bands and communities, with free and unsuspicious intercourse performing their evolutions. There are no signs of enmity, no attempt to devour each other. The different bands seem peaceably and complaisantly to move a little aside, as it were to make room for others to pass by.

But behold yet something far more admirable. See whole armies descending into an abyss, into the mouth of the bubbling fountain, they disappear! Are they gone forever? Is it real? I raise my eyes with terror and astonishment–I look down again to the fountain with anxiety, when behold them as it were emerging from the blue ether of another world, apparently at a vast distance, at their first appearance, no bigger than flies or minnows, now gradually enlarging, their brilliant colors begin to paint the fluid.

Now they come forward rapidly, and instantly emerge, with the elastic expanding column of chrystaline waters, into the circular basin or funnel. See now how gently they rise, some upright, others obliquely, or seem to lay as it were on their sides, suffering themselves to be gently lifted or born up, by the expanding fluid towards the surface, sailing or floating like butterflies in the cerulean ether. Then again they as gently descend, diverge and move off; when they rally, form again and rejoin their kindred tribes.

This amazing and delightful scene, though real, appears at first but as a piece of excellent painting. There seems no medium, you imagine the picture to be within a few inches of your eyes, and that you may without the least difficulty touch any one of the fish, or put your singer upon the crocodile’s eye, when it really is twenty or thirty feet under water. [168]

Although this paradise of fish may seem to exhibit a just representation of the peaceable and happy state of nature, which existed before the fall, yet in reality it is a mere representation. For the nature of the fish is the same as if they were in lake George or the river; but here the water or element in which they live and move, is so perfectly clear and transparent. It places them all on an equality with regard to their ability to injure or escape from one another; (as all river fish of prey, or such as feed upon each other, as well as the unwieldy crocodile, take their prey by surprise; secreting themselves under covert or in ambush, until an opportunity offers, when they rush suddenly upon them:) but here is no covert, no ambush, here the trout freely passes by the very nose of the alligator and laughs in his face, and the bream by the trout.

But what is really surprising, that the consciousness of each other’s safety or some other latent cause should so absolutely alter their conduct. For here is not the least attempt made to injure or disturb one another.

The sun passing below the horizon, and night approaching, I arose from my seat, and proceeding on arrived at my camp, kindled my fire, supped and reposed peaceably. And rising early employed the fore part of the day in collecting specimens of growing roots and seeds. In the afternoon, I left these Ellisian springs and the aromatic graves, and briskly descended the pellucid little river, re-entering the great lake. The wind being gentle and fair for Mount Royal, I hoisted sail and successfully crossing the N. West Bay, about nine miles, came to at Rocky Point, the West Cape or promontory, as we enter the river descending towards Mount Royal. [169]

These are horizontal slabs or flat masses of rocks, rising out of the lake two or three feet above its surface, and seem an aggregate composition or concrete of sand, shells and calcareous cement; of a dark grey or dusky color. This stone is hard and firm enough for buildings, and serve very well for light hand mill-stones, and when calcified affords a coarse lime. They lay in vast horizontal masses upon one another, from one to two or three feet in thickness, and are easily separated and broke to any size or form, for the purpose of building. Rocky Point is an airy cool and delightful situation, commanding a most ample and pleasing prospect of the lake and its environs, but here being no wood, I re-embarked and sailed down a little farther to the island in the bay, where I went on shore at a magnificent grove of magnolias and oranges, desirous of augmenting my collections. Arising early the next morning, and after ranging the groves and savannas, I returned, embarked again, and descending, called at Mount Royal, where I enlarged my collections; and bidding adieu to the gentleman and lady, who resided here, and who treated me with great hospitality on my ascent up the river; arrived in the evening at the lower trading house. [170]

Chapter Six

On my return from my voyage to the upper store, I understood the trading company designed for Cuscowilla; that they had been very active in their preparations, and would be ready to set off in a few days. I therefore availed myself of the little time allowed me to secure and preserve my collections against the arrival of the trading schooner, which was hourly expected, that every thing might be in readiness to be shipped on board her in case she should load again and return for Savanna during my absence.

Every necessary being now in readiness, early on a fine morning we proceeded. Attended by four men under the conduct of an old trader whom Mr. M’Latche had delegated to treat with the Cowkeeper and other chiefs of Cuscowilla on the subject of re-establishing the trade, &c. agreeable to the late treaty of St. Augustine, we began.

For the first four or five miles we travelled Westward, over a perfectly level plain which appeared before and on each side of us as a charming green meadow, thinly planted with low spreading Pine trees (P. palustri.) The upper stratum of the earth is fine white chrystaline sand. The very upper surface of which being mixed or incorporated with the ashes of burnt vegetables, renders it of sufficient strength or fertility to clothe itself perfectly, with a very great variety of grasses, herbage and remarkably low shrubs, together with a very dwarf species of Palmetto (Corypha pumila stipit. serratis.) [171]

Of the low shrubs many were new to me and of a very pleasing appearance, particularly a species of Annona (Annona incarna, floribus grandioribus paniculatis;) this grows three, four or five feet high, the leaves somewhat uniform or broad lanciolate, attenuating down to the petiole, of a pale or light green color, covered with a pubescence or short fine down. The flowers are very large, perfectly white and sweetly scented, many connected together on large loose panicles or spikes; the fruit of the size and form of a small cucumber, the skin or exterior surface somewhat rimose or scabrous, containing a yellow pulp of the consistence of a hard custard, and very delicious, wholesome food. This seems a variety, if not the same that I first remarked, growing on the Alatamaha near Fort Barrington, Charlotia and many other places in Georgia and East-Florida; and I observed here in plenty, the very dwarf decumbent Annona, with narrow leaves, and various flowers already noticed at Alatamaha (Annona pigmea.) Here is also abundance of the beautiful little dwarf Kalmea ciliata, already described. The white berried Empetrum, a very pretty evergreen, grows here on somewhat higher and drier knolls, in large patches or clumps, associated with Olea Americana, several species of dwarf Querci (Oaks) Vaccinium, Gordonia lasianthus, Andromeda ferruginia and a very curious and beautiful shrub which seems allied to the Rhododendron, Cassine, Rhamnus frangula, Andromeda nitida, &c. which being of dark green foliage, diversifies and enlivens the landscape. But what appears very extraordinary, is to behold here, depressed and degraded, the glorious pyramidal Magnolia grandiflora, associated amongst these vile dwarfs, and even some of them rising above it though not five feet high; yet still [172] showing large, beautiful and expansive white fragrant blossoms, and great heavy cones on slender procumbent branches, some even lying on the earth. The ravages of fire keep them down, as is evident from the vast excrescent tuberous roots, covering several feet of ground, from which these slender shoots spring.

In such clumps and coverts are to be seen several kinds of birds, particularly a species of jay; they are generally of an azure blue color, have no crest or tuft of feathers on the head. Nor are they as large as the great crested blue jay of Virginia, but are equally clamorous (pica glandaria cerulea non crestata.) The towee birds (fringilla erythrophthalma) are very numerous, as are a species of bluish grey butcher bird (lanius.) Here were also lizards and snakes. The lizards were of that species called in Carolina, scorpions. They are from five to six inches in length, of a slender form; the tail in particular is very long and small. They are of a yellowish clay color, varied with longitudinal lines or stripes of a dusky brown color, from head to tail; they are wholly covered with very small squamae, vibrate their tail, and dart forth and brandish their forked tongue after the manner of serpents, when they are surprised or in pursuit of their prey, which are scarabei, locustae, musci, and other insects, but I do not learn that their bite is poisonous, yet I have observed cats to be sick soon after eating them. After passing over this extensive level, hard, wet savanna, we crossed a fine brook or rivulet; the water cool and pleasant; its banks adorned with varieties of trees and shrubs, particularly the delicate Cyrilla racemifiora, Chionanthus, Clethra, Nyssa sylvatica, Andromeda nitida, Andromeda formosissima. Here were great quantities of a very [173] large and beautiful Filex osmunda, growing in great tufts or clumps. After leaving the rivulet we passed over a wet, hard, level glade or down, covered with a fine short grass, with abundance of low saw Palmetto, and a few shrubby Pine trees, Quercus nigra, Quercus sinuata or scarlet Oak: then the path descends to a wet bay-gale; the ground a hard, fine white sand, covered with black slush, which continued above two miles, when it gently rises the higher sand hills, and directly after passes through a fine grove of young long leaved Pines. The soil seemed here, loose, brown, coarse, sandy loam, though fertile. The ascent of the hill, ornamented with a variety and profusion of herbacious plants and grasses, particularly Amaryllis atamasco, Clitoria, Phlox, Ipomea, Convolvulus, Verbena corymbosa, Rucllia, Viola, &c. A magnificent grove of stately Pines, succeeding to the expansive wild plains we had a long time traversed, had a pleasing effect, rousing the faculties of the mind, awakening the imagination by its sublimity, and arresting every active inquisitive idea, by the variety of the scenery and the solemn symphony of the steady Western breezes, playing incessantly, rising and falling through the thick and wavy foliage.

The Pine groves passed, we immediately find ourselves on the entrance of the expansive airy Pine forests, on parallel chains of low swelling mounds, called the Sand Hills, their ascent so easy, as to be almost imperceptible to the progressive traveller, yet at a distant view, before us in some degree exhibit the appearance of the mountainous swell of the ocean immediately after a tempest. Yet, as we approach them, they insensibly disappear, and seem to be lost, and we should be ready to conclude [174] all to be a visionary scene, were it not for the sparkling ponds and lakes, which at the same time gleam through the open forests, before us and on every side, retaining them on the eye, until we come up with them. At last the imagination remains flattered and dubious, by their uniformity, being mostly circular or elliptical, and almost surrounded with expansive green meadows. Always a picturesque dark grove of Live Oak, Magnolia, Gordonia and the fragrant orange, encircling a rocky shaded grotto, of transparent water, on some border of the pond or lake; which, without the aid of any poetic fable, one might naturally suppose to be the sacred abode or temporary residence of the guardian spirit but is actually the possession and retreat of a thundering absolute crocodile.

Arrived early in the evening at the Halfway pond, where we encamped and stayed all night, this lake spreads itself in a spacious meadow, beneath a chain of elevated sand hills, the sheet of water at this time was about three miles in circumference. The upper end, and just under the hills, are surrounded by a crescent of dark groves, with a rocky grotto. Near this place, was a sloping green bank, terminating by a point of flat rocks, which shaded into the lake, and formed one point of the crescent that partly surrounded the vast grotto or basin of transparent waters, which is called by the traders a sink hole; a singular kind of vortex or conduit, to the subterranean receptacles of the waters; but though the waters of these ponds in the summer and dry seasons, evidently tend towards these sinks, yet it is so slow and gradual, as to be almost imperceptible. There is always a [175] meandering channel winding through the savannas or meadows, which receives the waters spread over them, by several lateral smaller branches, slowly conveying them along into the lake, and finally into the basin, and with them nations of the finny tribes.

Just by the little cape of flat rocks, we fixed our encampment, where I enjoyed a comprehensive and varied scene, the verdant meadows spread abroad, charmingly decorated by green points of grassy lawns and dark promontories of wood-land, projecting into the green plains.

Behold now at still evening, the sun yet streaking the embroidered savannas, armies of fish pursuing their pilgrimage to the grand pellucid fountain, and when here arrived, all quiet and peaceable, encircle the little cerulean hemisphere, descend into the dark caverns of the earth; where probably they are separated from each other, by innumerable paths, or secret rocky avenues. After encountering various obstacles, and beholding new and unthought of scenes of pleasure and disgust, after many days absence from the surface of the world, emerge again from the dreary vaults, and appear exulting in gladness, and sporting in the transparent waters of some far distant lake.

The various kinds of fish and amphibious animals, that inhabit these inland lakes and waters, may be mentioned here, as many of them here assembled, pass and re-pass in the lucid grotto. First the crocodile alligator; great brown spotted garr, accoutred in an impenetrable coat of mail; this admirable animal may be termed a cannibal amongst fish, as fish are his prey. When fully grown [176] he is from five to six feet in length, and of proportional thickness, of a dusky brown color, spotted with black. The Indians make use of their sharp teeth to scratch or bleed themselves with, and their pointed scales to arm their arrows. This fish is sometimes eaten, and to prepare them for food, they cover them whole in hot embers, where they bake them, the skin with the scales easily peel off, leaving the meat white and tender.

The mud fish is large, thick or round, but two feet in length; his meat white and tender, but soft and tastes of the mud, and is not much esteemed. The great devouring trout and catfish are in abundance; the golden bream or sunfish, the red bellied bream, the silver or white bream, the great yellow and great black or blue bream, also abound here. The last of these mentioned, is a large, beautiful and delicious fish; when full grown they are nine inches in length, and five to six inches in breadth; the whole body is of a dull blue or Indigo color, marked with transverse lists or zones of a darker color, scatteringly powdered with sky blue, gold and red specks; fins and tail of a dark purple or livid flesh color; the ultimate angel of the branchiostega forming a spatula. The extreme end of which is broad and circular, terminating like the feather of the peacock’s train, and having a brilliant spot or eye like it, being delicately painted with a fringed border of a fire color.

The great yellow or particolored bream is in form and proportion much like the fore-mentioned, but larger, from a foot to fifteen inches in length; the upper part of his body (i.e.) his back from head to tail, is of a dark clay and dusky color, with transverse dashes or blotches, of reddish [177] dull purple, or bluish, according to different exposures to light. The sides and belly of a bright pale yellow, the belly faintly stained with vermillion red, insensibly blended with the yellow on the sides, and all garnished with fiery, blue, green, gold and silver specks on the scales. The branchiostega is of a yellowish clay or straw color, the lower edge or border next the opening of the gills, is near a quarter of an inch in breadth, of a sea green or marine blue, the ulterior angle protrudes backwards to a considerable length, in the form of a spatula or feather, the extreme end dilated and circular, of a deep black or crow color, reflecting green and blue, and bordered round with fiery red, somewhat like red sealing wax, representing a brilliant ruby on the side of the fish; the fins reddish and edged with a dove color. They are deservedly esteemed a most excellent fish.

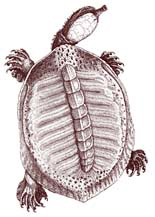

Here are, as well as in all the rivers, lakes and ponds of East Florida, the great soft shelled tortoise[2]. They are very large when full grown, from twenty to thirty and forty pounds in weight, extremely fat and delicious, but if eaten to excess they are apt to purge people not accustomed to eat their meat.

They are flat and very thin, two and a half feet in length, and eighteen inches in breadth across the back; in form, appearance and texture, very much resembling the sea turtle. The whole back shell, except the vertebrae or ridge, which is not at all prominent, and ribs on each side, are soft or cartilaginous, and easily reduced to a jelly when boiled. The anterior and posterior extremities of the back shell, appear to be embossed with round, [178] horny warts or tubercles. The belly or nether shell is but small and semi-cartilagenous, except a narrow cross bar connecting it at each end with the back shell, which is hard and osseous. The head is large and clubbed, of nearly an oval form, the upper mandible; however, is protruded forward, and truncated, somewhat resembling a swine’s snout, where at the extreme end the nostrils are placed. On each side of the root or base of this proboscis are the eyes, which are large; the upper beak is hooked and sharp, like a hawk’s bill; the lips and corners of the mouth large, tumid, wrinkled and barbed with long, pointed warts, which he can project and contract at pleasure. This gives the creature a frightful and disagreeable countenance. They bury themselves in the slushy bottoms of rivers and ponds, under the roots of flags and other aquatic herbage, leaving a hole or aperture just sufficient for their head to play through; in such places they withdraw themselves when hungry, and there seize their prey by surprise, darting out their heads as quick as lightning, upon the unwary animal that unfortunately strolls within their reach. They can extend their neck to a surprising length, which enables them to seize young fowl swimming on the surface of the water above them, which they instantly drag down. They are seen to raise their heads above the surface of the water, in the depths of the lakes and rivers, and blow, causing a faint puffing noise, somewhat like a porpoise. This is probably for pastime, or to charge themselves with a proper supply of fresh air. They are carnivorous, feeding on any animal they can seize, particularly young ducks, frogs and fish.

We had a large and fat one served up for our [179] supper. At first I apprehended we had made a very extravagant waste, not being able to consume one half of its flesh, though excellently well cooked. My companions; however, had no regard, being in the midst of plenty and variety, at any time within our reach, and to be obtained with little or no trouble or fatigue on our part. When herds of deer were feeding in the green meadows before us; there were flocks of turkeys, walking in the groves around us, and myriads of fish, of the greatest variety and delicacy, sporting in the chrystaline floods before our eyes. The vultures and ravens, crouched on the crooked limbs of the lofty pines, at a little distance from us, sharpening their beaks, in low debate, waited to regale themselves on the offal, after our departure from camp.

At the return of the morning, by the powerful influence of light; the pulse of nature becomes more active, and the universal vibration of life insensibly and irresistibly moves the wondrous machine. How cheerful and gay all nature appears. Hark! The musical savanna cranes, ere the chirping sparrow flirts from his grassy couch, or the glorious sun gilds the tops of the pines, spread their expansive wings, leave their lofty roosts, and repair to the ample plains. From Half-way Pond, we proceed Westward, through the high forests of Cuscowilla.

The appearance of the earth for five or six miles presented nearly the same scenes as heretofore. Now the sand ridges become higher, and their bases proportionally more extensive; the savannas [180] and ponds more expansive; the summit of the ridges more gravelly; here and there are heaps or piles of rocks, emerging out of the sand and gravel. These rocks are the same sort of concrete of sand and shells as noticed on St. Juan’s and the great lake. The vegetable productions nearly the same as already mentioned.

We gently descend again over sand ridges, cross a rapid brook rippling over the gravelly bed, hurrying the transparent waters into a vast and beautiful lake through a fine fruitful orange grove which magnificently adorns the banks of the lake to a great distance on each side of the capes of the creek. This is a fine situation for a capital town. These waters are tributary to St. Juan’s.

We alighted to refresh ourselves, and adjust our packs. Here are evident signs and traces of a powerful settlement of the ancients. We set off again and continued travelling over a magnificent pine forest, the ridges low, but their bases extensive, with proportional plains. The steady breezes gently and continually rising and falling fill the high lonesome forests with an awful reverential harmony, inexpressibly sublime, and not to be enjoyed any where, but in these native wild Indian regions.

Crossing another large deep creek of St. Juan’s, the country is a vast level plain, and the soil good for the distance of four or five miles, though light and sandy, producing a forest of stately pines and laurels, with some others; and a vast profusion of herbage, such as Rudbeckia, Helianthus, Silphium, Polymnia, Ruellia, Verbena, Rhexea, Convolvus, Sophora, Glycine, Vitia, Clitorea, Ipomea, Urtica, Salvia graviolens, Viola and many more. How cheerful and social is the rural converse of the various tribes of tree frogs, whilst they look to heaven for prolific showers!