In 1696, the English Quaker Jonathan Dickinson (1663-1722) set off on a commercial venture from Port Royal, Jamaica for Philadelphia. His companions included his wife, their six-month-old son, commander Joseph Kirle, the mariners, ten slaves, and other passengers and merchants. Before

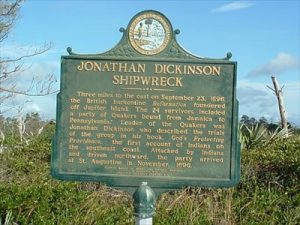

Waymark at the entrance of Jonathan Dickinson State Park, located in Martin County, Florida. Text reads: “Three miles to the east on Sept. 23, 1696, the British barkentine Reformation foundered off Jupiter Island. The 24 survivors included a party of Quakers bound from Jamaica to Pennsylvania. Leader of the Quakers was Jonathan Dickinson who described the trials of the group in his book, “God’s Protecting Providence”, the first account of Indians on the southeast coast. Attacked by Indians and driven northward, the party arrived at St. Augustine in November, 1696.”

reaching Philadelphia, Dickinson’s ship, the Reformation, encountered harsh weather and wrecked off the coast of present day Palm Beach island on the south side of present-day Jupiter Inlet. In the storm, the Reformation was separated from its accompanying fleet. Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal, first printed in 1699 and originally titled God’s Protecting Providence, Man’s Surest Help and Defense, In Times of the Greatest Difficulty, and most Eminent Danger, […] From the cruel Devouring Jaws of the Inhumane Canibals of Florida, is a narrative of shipwreck and captivity. Though originally written as a report to the Spanish governor, the account was published by the members of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, who believed the narrative exemplified God’s guidance, intervention, and deliverance.

Dickinson and his companions spent more than seven months in captivity, suffering throughout from hunger, cold, and sickness, before arriving in Philadelphia. Many readers view Robert Barrow’s death at the end of the narrative as martyrdom. The following selection begins when the shipwrecked Reformation first struck the coast of Florida.

Edited by Mikaela Perron, University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Further Reading

Andrews, Charles M., and Jonathan Dickinson. “God’s Protecting Providence: A Journal by Jonathan Dickinson.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 21.2 (1942): 107-26. Web.

Dickinson, Jonathan. Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal or, God’s Protecting Providence. Eds. Evangeline Walker Andrews and Charles McLean Andrews. New Haven, New Haven: Yale U P, 1945. Print.

Voigt, Lisa. Writing Captivity in the Early Modern Atlantic: Circulations of Knowledge and Authority in the Iberian and English Imperial Worlds. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the U North Carolina P, 2009. Print.

Jonathan Dickinson. God’s Protecting Providence, man’s surest help and defence, in times of the greatest difficulty, and most eminent danger: evidenced in the remarkable deliverance of Robert Barrow, with divers other persons, from the devouring waves of the sea; amongst which they suffered shipwrack: and also, from the cruel, devouring jaws of the inhumane canibals of Florida [1700]. From Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal, edited by Evangeline Walker Andrews and Charles McLean Andrews. New Haven: Yale U P, 1945.

The 7 Month, 23; the 4 day of the week.

About one o’clock in the morning we felt our vessel strike some few strokes, and then she floated again for five or six minutes before she ran fast aground, where she beat violently at first. The wind was violent and it was very dark, that our mariners could see no land; the seas broke over us that we were in a quarter of an hour floating in the cabin: we endeavored to get a candle lighted, which in a little time was accomplished. By this time we felt the vessel not to strike so often but several of her timbers were broken and some plank started. The seas continued breaking over us and no land to be seen; we concluded to keep in the vessel as long as she would hold together. About the third hour this morning we supposed we saw the land at some considerable distance, and at this time we found the water began to run out of the vessel. And at daylight we perceived we were upon the shore, on a beach lying in the breach of the sea which at times as the surges of the sea reversed was dry. In taking a view of our vessel, we found that the violence of the weather had forced many sorts of the seabirds on board of our vessel, some of which were by force of the wind blown into and under our hen-cubs and many remained alive. Our hogs and sheep were washed away and swam on shore, except one of the hogs which remained in the vessel. We rejoiced at this our preservation from the raging seas; but at the same instant feared the sad consequences that followed: yet having hopes still we got our sick and lame on shore, also our provisions, with spars and sails to make a tent. I went with one Negro to view the land and seek the most convenient place for that purpose; but the wilderness country looked very dismal, having no trees, but only sand hills covered with shrubby palmetto, the stalks of which were prickly, that there was no walking amongst them. I espied a place almost a furlong within that beach being a bottom; to this place I with my Negro soon cut a passage, the storm and rain continuing. Thither I got my wife and sick child being six months and twelve days old, also Robert Barrow an aged man, who had been sick about five or six months, our master, who some days past broke his leg, and my kinsman Benjamin Allen, who had been very ill with a violent fever most part of the voyage: these with others we got to the place under the shelter of some few bushes which broke some of the wind, but kept none of the rain from them; I got a fire made. The most of our people were getting provisions ashore; our chests, trunks and the rest of our clothing were all very wet and cold.

About the eighth or ninth hour came two Indian men (being naked except a small piece of platted work of straws which just hid their private parts, and fastened behind with a horsetail in likeness made of a sort of silk-grass) from the southward, running fiercely and foaming at the mouth having no weapons except their knives: and forthwith not making any stop; violently seized the two first of our men they met with who were carrying corn from the vessel to the top of the bank, where I stood to receive it and put it into a cask. They used no violence for the men resisted not, but taking them under the arm brought them towards me. Their countenance was very furious and bloody. They had their hair tied in a roll behind in which stuck two bones shaped one like a broad arrow, the other a spearhead. The rest of our men followed from the vessel, asking me what they should do whether they should get their guns to kill these two; but I persuaded them otherwise desiring them to be quiet, showing their inability to defend us from what would follow; but to put our trust in the Lord who was able to defend to the uttermost. I walked towards the place where our sick and lame were, the two Indian men following me. I told them the Indians were come and coming upon us. And while these two (letting the men loose) stood with a wild, furious countenance, looking upon us I bethought myself to give them some tobacco and pipes, which they greedily snatched from me, and making a snuffing noise like a wild beast, turned their backs upon us and run away.

We communed together and considered our condition, being amongst a barbarous people such as were generally accounted man-eaters, believing those two were gone to alarm their people. We sat ourselves down, expecting cruelty and hard death, except it should please the Almighty God to work wonderfully for our deliverance. In this deep concernment some of us were not left without hopes; blessed be the name of the Lord in Whom we trusted.

As we were under a deep exercise and concernment, a motion arose from one of us that if we should put ourselves under the denomination of the Spaniards (it being known that that nation had some influence on them) and one of us named Solomon Cresson speaking the Spanish language well, it was hoped this might be a means for our delivery, to which the most of the company assented.

Within two or three hours after the departure of the two Indians, some of our people being near the beach or strand returned and said the Indians were coming in a very great number all running and shouting. About this time the storm was much abated, the rain ceased, and the sun appeared which had been hid from us many days. The Indians went all to the vessel, taking forth whatever they could lay hold on, except rum, sugar, molasses, beef and pork.

But their Casseekey (for so they call their king) with about thirty more came down to us in a furious manner, having a dismal aspect and foaming at the mouth. Their weapons were large Spanish knives, except their Casseekey’s who had a bagganet that belonged to the master of our vessel: they rushed in upon us and cried Nickaleer Nickaleer. We understood them not at first: they repeating it over unto us often. At last they cried Epainia or Spaniard, by which we understood them that at first they meant English; but they were answered to the latter in Spanish yea to which they replied, No Spainia No, but all cried out, Nickaleer, Nickaleer. We sitting on our chests, boxes and trunks, and some on the ground, the Indians surrounded us. We stirred nor moved not; but sat all or most of us very calm and still, some of us in a good frame of spirit, being freely given up to the will of God.

Whilst we were thus sitting, as a people almost unconcerned, these bloody minded creatures placed themselves each behind one kicking and throwing away the bushes that were nigh or under their feet; the Casseekey had placed himself behind me, standing on the chest which I sat upon, they all having their arms extended with their knives in their hands, ready to execute their bloody design, some taking hold of some of us by the heads with their knees set against our shoulders. In this posture they seemed to wait for the Casseekey to begin. They were high in words which we understood not. But on a sudden it pleased the Lord to work wonderfully for our preservation, and instantly all these savage men were struck dumb, and like men amazed the space of a quarter of an hour, in which time their countenances fell, and they looked like another people. They quitted their places they had taken behind us, and came in amongst us requiring to have all our chests, trunks and boxes unlocked; which being done, they divided all that was in them. Our money the Casseekey took unto himself, privately hiding in the bushes. Then they went to pulling off our clothes, leaving each of us only a pair of breeches, or an old coat, except my wife and child, Robert Barrow and our master, from whom they took but little this day.

Having thus done, they asked us again, Nickaleer, Nickaleer? But we answered by saying Pennsylvania.

We began to enquire after St. Augustine, also would talk of St. Lucie, which was a town that lay about a degree to the northward. But they cunningly would seem to persuade us that they both lay to the southward. We signified to them that they lay to the northward. And we would talk of the Havana that lay to the southward. These places they had heard of and knew which way they lay.

At length the Casseekey told us how long it was to St. Lucie by days’ travel; but cared not to hear us mention St. Augustine. They would signify by signs we should go to the southward. We answered that we must go to the northward for Augustine. When they found they could not otherwise persuade us, they signified that we should go to the southward for the Havana, and that it was but a little way.

We gave them to understand that we came that way and were for the northward; all which took place with them. We perceived that the Casseekey’s heart was tendered towards us; for he kept mostly with us and would the remaining part of this day keep off the petty robbers which would have had our few rags from us. Sometime before night we had a shower of rain, whereupon the Casseekey made signs for us to build some shelter; upon which we got our tent up and some leaves to lie upon.

About this time our vessel lay dry on shore and the Indians gathered themselves together men and women, some hundreds in numbers. Having got all the goods out of the vessel and covered the bay for a large distance, opened all the stuffs and linens and spread them to dry, they would touch no sort of strong drink, sugar, nor molasses, but left it in the vessel. They shouted and made great noises in the time of plunder. Night coming on the Casseekey put those chests and trunks which he had reserved for himself into our tent; which pleased us, and gave an expectation of his company for he was now become a defender of us from the rage of others. The Casseekey went down to the waterside amongst his people and returned with three old coats that were wet and torn, which he gave us; one whereof I had. We made a fire at each end of our tent and laid ourselves down, it being dark: but hearing hideous noises and fearing that they were not satisfied, we expected them upon us. The chief Indian (or Casseekey) lay in the tent upon his chests. And about midnight we heard a company of Indians coming from the vessel towards us, making terrible shouts, and coming fiercely up to the tent, the Casseekey called to them; which caused them to stand. It seemed, they had killed a hog and brought him: So the Casseekey asked us, if we would eat the hog? Solomon Cresson, by our desire answered him, that we used not to eat at that time of the night: whereupon they threw the hog down before the tent, and the Casseekey sent them away. They went shouting to the sea-shore, where there were some hundreds of them revelling about our wreck.

The 7 month, 25; the 6 day of the week.

This morning having purposed to endeavor for liberty to pass to the northward, Solomon opened the matter to the Casseekey; who answered we must go to his town to the southward.

This occasioned us to press him more urgently to let us go to St. Lucie (this place having a Spanish name supposed to have found it under the government of that nation, whence we might expect relief). But the Casseekey told us that it was about two or three days’ journey thither and that when we came there, we should have our throats and scalps cut and be shot, burnt and eaten. We thought that information was but to divert us; so that we were more earnest to go but he sternly denied us, saying, we must go to his town.

About eight o’clock this morning the Casseekey came into our tent and set himself amongst us, asking the old question, Nickaleer, Nickaleer? directing his speech to one particular of us, who in simplicity answered, yes. Which caused the Casseekey to ask the said person, if another person which he pointed to, was Nickaleer? He answered, yes. Then he said, Totus (or all) Nickaleer, and went from amongst us. Returning in a short time with some of his men with him, and afresh they went greedily to stripping my wife and child, Robert Barrow and our master who had escaped it till now. Thus were we left almost naked, till the feud was something abated and then we got somewhat from them which displeased some of them. We then cut our tents in pieces, and got the most of our clothing out of it: which the Indians perceiving, took the remains from us. We men had most of us breeches and pieces of canvas, and all our company interceded for my wife that all was not taken from her. About noon the Indians having removed all their plunder off the bay, and many of them gone, a guard was provided armed with bows and arrows, with whom we were summoned to march and a burden provided for everyone to carry that was any ways able. Our master with his broken leg was helped along by his Negro Ben. My wife was forced to carry her child, they not suffering any of us to relieve her. But if any of us offered to lay down our burden, we were threatened to be shot. Thus were we forced along the beach bare-footed.

We had saved one of the master’s quadrants, and seamen’s calendar, with two other books. As we walked along the bay (the time suiting) our mate Richard Limpeney took an observation, and we found ourselves to be in the latitude of twenty-seven degrees and eight minutes. Some of the Indians were offended at it: when he held up his quadrant to observe, one would draw an arrow to shoot him; but it pleased God hitherto to prevent them from shedding any of our blood.

One passage I have omitted. Two of our mariners named Thomas Fownes and Richard Limpeney went forth this morning from our tent down to the bay where the Indians were, and viewing of them at some distance, an Indian man came running upon them, with his knife in his hand, and took hold of Thomas Fownes to stab him; but the said Thomas fell on his knees, using a Spanish ceremony, and begged not to kill him; whereupon the Indian desisted, and bid him be gone to the place from which he came. The said Thomas at his return acquainted us how narrowly he had escaped.

After we had traveled about five miles along the deep sand, the sun being extreme hot, we came to an inlet. On the other side was the Indian town, being little wigwams made of small poles stuck in the ground, which they bended one to another, making an arch, and covered them with thatch of small palmetto-leaves. Here we were commanded to sit down, and the Casseekey came to us, who with his hand scratched a hole in the sand about a foot deep, and came to water, which he made signs for us to come and drink. We, being extreme thirsty, did; but the water was almost salt. Whilst we sat here, we saw great fires making on the other side of the inlet, which some of us thought was preparing for us. After an hour’s time being spent here at length came an Indian with a small canoe from the other side and I with my wife and child and Robert Barrow were ordered to go in. The same canoe was but just wide enough for us to sit down in. Over we were carried, and being landed, the man made signs for us to walk to the wigwams, which we did; but the young Indians would seem to be frighted and fly from us. We were directed to a wigwam, which afterwards we understood to be the Casseekey’s. It was about man-high to the top. Herein was the Casseekey’s wife and some old women sitting on a cabin made of sticks about a foot high covered with a mat; they made signs for us to sit down on the ground; which we did, the Casseekey’s wife having a young child sucking at her breast gave it to another woman, and would have my child; which my wife was very loath to suffer; but she would not be denied, took our child and suckled it at her breast viewing and feeling it from top to toe; at length returned it to my wife, and by this time was another parcel of our people come over; and sitting down by the wigwam side our Indian brought a fish boiled on a small palmetto leaf and set it down amongst us, making signs for us to eat; but our exercise was too great for us to have any inclination to receive food. At length all our people were brought over, and afterwards came the Casseekey. As soon as he came to his wigwam he set himself to work, got some stakes and stuck them in a row joining to his wigwam and tied some sticks whereon were these small palmettos, tied and fastened them to the stakes about three foot high; and laid two or three mats made of reeds down by this shelter; which, it seems, he made for us to break the wind off us; and ordered us to lie down there; which we did, as many as the mats would hold; the rest lay on the ground by us. The Casseekey went into his wigwam and seated himself on his cabin cross-legged having a basket of palmetto berries brought him, which he eat very greedily: after which came some Indians unto him and talked much. Night came on; the moon being up, an Indian, who performeth their ceremonies stood out, looking full at the moon making a hideous noise, and crying out acting like a mad man for the space of half an hour; all the Indians being silent till he had done: after which they all made fearful noise some like the barking of a dog, wolf, and other strange sounds. After this, one gets a log and sets himself down, holding the stick or log upright on the ground, and several others getting about him, made a hideous noise, singing to our amazement; at length their women joined consort, making the noise more terrible. This they continued till midnight. Towards morning was great dews: our fire being expended, we were extreme cold.

The 7 month, 26; the 7 day of the week.

This morning the Casseekey looking on us with a mild aspect, sent his son with his striking staff to the inlet to strike fish for us; which was performed with great dexterity; for some of us walked down with him, and though we looked very earnestly when he threw his staff from him could not see a fish at which time he saw it, and brought it on shore on the end of his staff. Sometimes he would run swiftly pursuing a fish, and seldom missed when he darted at him. In two hours’ time he got as many fish as would serve twenty men: there were others also fishing at the same time, so that fish was plenty: but the sense of our conditions stayed our hungry stomachs: for some amongst us thought they would feed us to feed themselves.

The Casseekey went this morning towards our vessel; in his absence the other Indians looked very untowardly upon us, which created a jealousy of their cruelty yet to come.

This afternoon we saw a great fire nigh the place of our vessel; whereupon we concluded that our vessel and our boat were burnt: whereupon we were almost confirmed that they designed to destroy us. About sunsetting the Casseekey came home: we spake to him; he answered us and seemed very affable; which we liked well. Night drawing on and the wind shifting northward, we removed our shelter, and added the mats to it to break the wind off us, which blowed cold, and laid ourselves on the sand. About an hour within night came a parcel of Indians from the southward being all armed with bows and arrows and coming near our tent some of us espied them whereupon they squatted down. This seemed a fresh motive of danger, and we awakened those of us that were fallen asleep, and bid them prepare, for things seemed dangerous, we supposing they were come to forward our destruction or to carry us to the southward. They sat thus a considerable time; at length they distributed themselves to the wigwams. Thus would danger often appear unto us, and almost swallow us up; but at times we should be set over it, having a secret hope that God would work our deliverance, having preserved us from so many perils.

Sometime before night Robert Barrow was exhorting us to be patient and in a godly manner did he expound that text of scripture: Because thou hast kept the word of my patience &c. Rev., 3 Chap., 10 ver., after which he ended with a most fervent prayer desiring of the Lord that whereas He had suffered us to be cast amongst a barbarous and heathenish people, if that it was His blessed will, he would preserve and deliver us from amongst them, that our names might not be buried in oblivion; and that he might lay his body amongst faithful friends: and at the close of his prayer, he seemed to have an assurance that his petition would be granted. In all which some of us were livingly refreshed and strengthened.

The 7 month, 27; the 1 day of the week.

This morning we again used our endeavors with the Casseekey, that we might go to the northward for Augustine. His answer was, [we should go to the southward: for if we went to the northward,] we should be all killed; but at length we prevailed, and he said, on the morrow we should go. Hereupon he took three Negro men (one of Joseph Kirle’s and two of mine) and with a canoe went up the sound.

This day the Indians were busy with what they had taken out of our vessel, and would have employed all of us to do, some one thing, some another for them; but we not knowing the consequence endeavored to shun it, and would deny their demands.

But some of our men did answer their desires in making and sewing some cloth together, stringing our beds, mending of locks, of the chests, &c. Whatever they thought was amiss they would be putting upon us to mend, still we wholly refused. At which time I heard a saying that came from one of the chief Indians, thus “English Son of a Bitch,” which words startled me; for I do believe they had had some of our nation in their possession, of whom they had heard such an expression: I passed away from the wigwam with much trouble.

This day being the first day of the week, we having a large Bible and a book of Robert Barclay’s, some one or other was often reading in them. But being most of us sat together, Robert Barrow desired our people to wait upon the Lord: in which time Robert had a word in season unto us, and afterwards went to prayer, all the Indians coming about us, and some younger sort would be mocking; but not to our disturbance. The elder sort stood very modestly the whole time. After prayer ended, they all withdrew quietly: but some of them (especially the Casseekey’s eldest son) would take great delight in our reading, and would take the Bible or other book, and give to one or other to read; the sound of which pleased them, for they would sit quietly and very attentively to hear us.

The Casseekey having been gone most part of the day with three Negroes (about the third hour in the afternoon we saw two of our Negroes) in our boat coming over the bar into the inlet. We rejoiced to see our boat, for we thought she had been burnt. Our Negroes told us, they went up sound with the Casseekey and landed near the place where our tent had been: the chief business was to remove the money from one place to another, and bury it. This old man would trust our people, but not his own. After that was done, they went to the place where our vessel was burnt; they launched our boat, in which the old Casseekey put his chests, wherein was our linen and other of our trade: also they got a small rundlet which they filled with wine out of a quarter cask that was left and brought sugar out of the wreck which was not consumed with the fire. But this time came the Casseekey and other Negro in the canoe. He told us, on the morrow we should go with our boat: this was cheerful news unto us. All the time some Indians had been out, and brought home some oysters, and the Casseekey gave us some, bidding us take what we had a mind to. A little before night the Casseekey opened his chests and boxes; and his wife came and took what was in them from him: but he seemed very generous to my wife and child, and gave her several things which were useful to her and our child.

Our boat was very leaky; so we got her into a creek to sink her, that the water might swell her.

The 7 month, 28; the 2 day of the week.

This morning we waited an opportunity to get leave to depart, which was granted us: whereupon we asked for such things as they did not make use of; viz. a great glass, wherein was five or six pound of butter; some sugar; the rundlet of wine: and some balls of chocolate: all which was granted us; also a bowl to heave water out of the boat. But the Casseekey would have a Negro boy of mine, named Caesar, to which I could not tell what to say; but he was resolved on it. We got down to the waterside, and sent all our people over that were to travel: and Joseph Kirle, Robert Barrow, I, my wife and child with two of our mariners went in the boat, and rowed along shore northwards; but the Casseekey would have us to have gone with our boat up the sound. We supposed the sound was a great river; and therefore were not willing to take his advice, having no knowledge; but his counsel was good, as we found afterwards; for the conveniency of passage.

The Casseekey and some other Indians went with our people towards our wreck, we rowing along shore, and our boat very leaky, that one person had employ enough to heave out the water.

Just before we left the Indian town, several Indians were for taking the little clothes and rags we had got; but calling out to the Casseekey, he would cause them to let us alone.

Solomon Cresson was mightily in one Indian’s favor, who would hardly stir from his wigwam, but Solomon must be with him, and go arm in arm; which Indian amongst his plunder had a morning gown, which he put on Solomon, and Solomon had worn it most of the time we were there; but when the time of our departure came an Indian unrobed him, and left only a pair of breeches, and seemed very angry.

It was high noon when we left our wreck (she being burnt down to her floor timbers which lay in the sand) we setting forward, some in the boat, the rest traveled along shore; and a little before sun-setting, our people came up with abundance of small fish that had been forced on shore, as we may suppose, by the storm that drove us ashore (they lying far from the water, being much tainted), covered the shore for nigh a mile in length: of which our people gathered as many as they could carry. About sun-setting we put on shore to refresh ourselves, and take a small respite; also to take my kinsman Benjamin Allen into our boat: for this afternoon in his travel he was taken with a fever and ague, and we had much trouble to get him along, he having been sick nigh unto death (being first taken the day before we left Bluefields Road) until about a week before we were cast away.

One of my Negroes had saved a tinder-box and flint, and we had reserved two knives, by which means we got a fire, though with much difficulty, for our tinder was bad, and all the wood salt-water-soaken: which being accomplished, we broiled all our fish, feeding heartily of some of them, and the rest we kept not knowing when we should be thus furnished again; for which some of us were truly thankful to the God of all our mercies.

Having a large fire many of us got under the lee of it, and others buried themselves in the sand, in hopes to get a little sleep, that we might be somewhat refreshed, and thereby be the better enabled some to travel and some to row the remaining part of the night: but the sand flies and the mosquitoes were so extreme thick that it was impossible. The moon shining, we launched our boat I and my wife and child, the master, Robert Barrow, my kinsman Allen, Solomon Cresson, Joseph Buckley and the master’s Negro went in our boat; the rest traveled along shore. About midnight, or a little after, our people came by an Indian town; the Indians came out in a great number, but offered no violence more than endeavoring to take from them what little they had: but making some small resistance, the Indians were put by their purpose. They were very desirous to have us come on shore, and would hail us; but our people would have us keep off. We were got among a parcel [of] breakers, and so had much ado to get out to sea.

The 7 month, 29; the 3 day of the week.

This morning about sun-rising we stood in for the land, and looked out for our people, but could not see them, therefore we lay by for the space of two hours and at length saw them coming along with a great many Indians with them. When they came abreast with us, the Indians wafted us ashore; but we refused, perceiving they were wickedly bent; they would be ever and anon snatching one thing or another: at which time our people would point to us in the boat; but perceiving they could not get us ashore, in some few hours left them.

This day noon Joseph Kirle having his quadrant and calendar, took an observation, being in latitude 27 deg. 45 min. About one o’clock we saw two Indians with bows and arrows running to meet our people; who when they saw them, at first they made a halt and afterwards retreated: at which the Indians let fly an arrow; which narrowly escaped one of them. Whereupon they stopped; the Indians looked strangely on them; but our people set forwards, and the Indians with them until they came to the Indian town. We saw our people go into the wigwams, but stayed a very short time; for the Indians were for taking those pieces of canvas they had from them. They got some water and set forward again; the two Indians still followed them. About this time we saw a sail to the eastward, and we supposing it at first to be a brigantine, agreed to follow her; but in a small time we made it to be a canoe or boat with two masts and sails. She stood in for the shore; but as soon as they espied us she bore away; and when she saw we made not after her, she stood ashore again for the Indian town; hereupon a jealousy got amongst us that she might go on shore and get strong with men, and then come after us; whereupon we rowed very hard and kept an offing for some hours; but finding they came not out, we stood towards the shore again. This day was extreme hot and we had no water since we left the Indian town to the southward of our wreck, called by the name of Hoe-Bay; therefore we were desirous to get on shore, but when we endeavored it, we could not; for the seas swelling very much, and came rolling from the eastward: so that the seas run very hollow, and broke almost a mile from the shore. Our master said it was impossible to get on shore alive: but I being under some exercise was desirous to be on shore, and thereupon did express myself to the rest of our people; they stated the danger; all which I was as sensible of as they, yet I could not rest but insisted on going ashore. The master and men said we should not save our lives; but I gained so far, that they attempted and were got within half a mile of the shore; but the seas came on us so large and hollow that one sea had liked to have overwhelmed us: we just got atop of it before it broke. There was then no persuading them to go further, but we stood off, and designed to keep off all night, our people being very weary and the sun setting; we divided one half to get some sleep, the other to watch and keep the boat’s head to the sea. The weather looked as though it would be bad, and the sea increased; whereupon I began afresh to persuade them to go on shore. All were desirous, but thought it impossible. At length we resolved to venture; and so committing ourselves to the protection of the Almighty God, we stood in for the shore, and made signs to our people that we designed it. And it pleased God to order it so that we went on shore, as though there had been a lane made through the breakers, and were carried to the top of the bank, where we got aged Robert Barrow, my wife and child out of the boat, before ever a sea came to fill us; which did, as soon as they were got out: but we got our boat up from the wash of the sea.

The two Indians were for taking off our clothes, (which would not cover our bodies) but we not being willing to yield, they would snatch a piece from one and a bit from another, and run away with that, and then come again and do the like. These two Indians took away what was given to my wife and child which we knew not how to help, but exercised patience.

We inquired how far it was from St. Lucie (one of them speaking a little Spanish) and by signs we understood it was not far. They made signs that when we came there we should be put to most cruel death but we hoped otherwise.

At this place within the land, and over the sound our people said, before it was dark, they saw two or three houses, which looked white, though they were plastered with lime; which put us in hopes that there were Spaniards there; so we set forward as the Indians directed for St. Lucie. They made signs that we should come to an inlet of the sea, and on the other side was St. Lucie. We traveled about four miles and came to the inlet, but saw no settlement on the other side; so we concluded to lie there all night. We saw the track of a large bear and other wild beasts; whereupon we set to work to get wood and then a fire. Abundance of mosquitoes and sand-flies hindered our rest, to remedy which we digged holes in the sand, got some grass and laid it therein to lie upon, in order to cover ourselves from the flies, which most of us did; but it being extreme cold, and firing scarce, we had little comfort.

About midnight we sent our people to see if they could get off our boat, and bring it into the inlet, that we might get over to the other side. They went and launched her, but the sea was so rough that there was no possibility of getting her off, for she was soon filled, and put to swim, and they, boat and all, were driven on shore again.

Whilst our people were gone for the boat, we espied some Indians in a canoe with their torch a-fishing: we sent for Solomon (who was gone to launch the boat) expecting they would come, seeing fires, and we should not tell what to say to them; but they did not. Here we lay watching, for no rest could be taken.

The 7 month, 30; the 2 day of the week.

This morning by break of day we saw a small canoe from the other side put off shore with two Indians, in her going up the river (or sound) a-fishing. We hailed them in Spanish, and as soon as they heard and saw us, they made to the shore with all speed, and away to their town they run. We perceiving they were shy of us, began to doubt of their amity which we had so much depended on; whereupon we counseled our people how to deport themselves, especially our Negroes. About sun-rising we saw the Indians coming, running a very great number with their bows and arrows to the inlet; where having five or six canoes, they got into them as many as those canoes could hold. Others took the water, and swam over unto us; they came in the greatest rage that possibly a barbarous people could. Solomon began to speak Spanish to them; but they answered not, till they came ashore some distance from us; and then coming running upon us, they cried out, Nickaleer, Nickaleer. We sat all still expecting death, and that in a most barbarous manner. They that did speak unto them could not be heard: but they rushed violently on us rending and tearing those few clothes we had: they that had breeches had so many about them, that they hardly touched the ground till they were shaken out of them. They tore all from my wife, and espying her hair-lace, some were going to cut it hair and (all) away to get it, but, like greedy dogs, another snatched and tore it off. As for our poor young child, they snatched from it what little it had, as though they would have shaken and torn it, limb from limb. After they had taken all from us but our lives, they began to talk one to another, vehemently foaming at mouth, like wild boars, and taking their bows and arrows with other weapons, cried out Nickaleer, Nickaleer. Solomon spake in Spanish to them, and said we were Spaniards; but they would not hear him, and continued crying out Nickaleer, Nickaleer, withal drawing their arrows to the head. But suddenly we perceived them to look about and listen, and then desisted to prosecute their bloody design. One of them took a pair of breeches and gave it to my wife. We brought our great Bible and a large book of Robert Barclay’s to this place. And being all stripped as naked as we were born, and endeavoring to hide our nakedness; these cannibals took the books, and tearing out the leaves would give each of us a leaf to cover us; which we took from them: at which time they would deride and smite us; and instantly another of them would snatch away what the other gave us, smiting and deriding us withal.

Robert Barrow with myself, wife and child were ordered to go in to a canoe to be carried to the other side of the inlet, being a furlong over, four Indians being in the canoe to paddle. When we came to the other side within a canoe’s length or two of the shore, a number of Indians with their bows and arrows came running into the water, some to their knees, some deeper, having their bows and arrows drawn up, crying out Nickaleer, Nickaleer; which they continued without ceasing. The Indians that brought us over leaped out of the canoe, and swam ashore, fearing they should be shot; but in this juncture it pleased God to tender the hearts of some of them towards us; especially the Casseekey his wife, and some of the chiefest amongst them, who were made instruments to intercede for us, and stop the rage of the multitude, who seemed not to be satisfied without our blood. The Casseekey ordered some to swim, and fetch the canoe ashore; which being done, his wife came in a compassionate manner and took my wife out of the canoe, ordering her to follow her, which we did some distance from the inlet-side, and stood till all our people were brought over, which in a little time was done. But the rage of some was still great, thirsting to shed our blood, and a mighty strife there was amongst them: some would kill us, others would prevent it. And thus one Indian was striving with another. All being got over, [we] were to walk along the seashore to their town: in this passage we most of us felt the rage of some of them, either by striking or stoning, and divers arrows were shot: but those that were for preserving us would watch those that were for destroying us: and when some of them would go to shoot, others of them would catch hold of their bows or arm. It was so ordered that not one of us was touched with their arrows; several of us were knocked down, and some tumbled into the sea. We dared not help one another; but help we had by some of them being made instrumental to help us. My wife received several blows, and an Indian came and took hold of her hair, and was going either to throat or something like it, having his knife nigh her throat; but I looked at him, making a sign that he should not, so he desisted: at which time another Indian came with a handful of sea-sand and filled our poor child’s mouth. By this time the Casseekey’s wife came to my wife seeing her oppressed, and they pulled the sand out of our child’s mouth, and kept by my wife until we got into the Casseekey’s house, which was about forty foot long and twenty-five foot wide, covered with palmetto leaves both top and sides. There was a range of cabins, or a barbecue on one side and two ends. At the entering on one side of the house a passage was made of benches on each side leading to the cabins. On these benches sat the chief Indians, and at the upper end of the cabin was the Casseekey seated. A kind of debate was held amongst them for an hour’s time. After which Solomon and some others were called to the Casseekey; and were seated on the cabin; where the Casseekey talked to Solomon in the Spanish language, but could not hold a discourse. In a little time some raw deer skins were brought in and given to my wife and Negro women, and to us men such as the Indian men wear, being a piece of platwork of straws wrought of divers colors and of a triangular figure, with a belt of four fingers broad of the same wrought together, which goeth about the waist and the angle of the other having a thing to it, coming between the legs, and strings to the end of the belt; all three meeting together are fastened behind with a horsetail, or a bunch of silk-grass exactly resembling it, of a flaxen color, this being all the apparel or covering that the men wear; and thus they clothed us. A place was appointed for us, mats being laid on the floor of the house, where we were ordered to lie down. But the place was extremely nasty; for all the stones of the berries which they eat and all the nastiness that’s made amongst them lay on their floor, that the place swarmed with abundance of many sorts of creeping things; as a large black hairy spider, which hath two claws like a crab; scorpions; and a numberless number of small bugs. On these mats we lay, these vermin crawling over our naked bodies. To brush them off was like driving off mosquitoes from one where they are extreme thick. The Indians were seated as aforesaid, the Casseekey at the upper end of them, and the range of cabins was filled with men, women and children, beholding us. At length we heard a woman or two cry, according to their manner, and that very sorrowfully, one of which I took to be the Casseekey’s wife which occasioned some of [us] to think that something extraordinary was to be done to us. We heard a strange sort of a noise which was not like unto a noise made by a man; but we could not understand what nor where it was; for sometimes it sounded to be in one part of the house, sometimes in another, to which we had an ear. And indeed our ears and eyes could perceive or hear nothing but what was strange and dismal; and death seemed [to have] surrounded us. But time discovered this noise unto us. The occasion of it was thus: In one part of this house where the fire was kept, was an Indian man, having a pot on the fire wherein he was making a drink of the leaves of a shrub (which we understood afterwards by the Spaniard, is called casseena), boiling the said leaves, after they had parched them in a pot; then with a gourd having a long neck and at the top of it a small hole which the top of one’s finger could cover, and at the side of it a round hole of two inches diameter, they take the liquor out of the pot and put it into a deep round bowl, which being almost filled containeth nigh three gallons. With this gourd they brew the liquor and make it froth very much. It looketh of a deep brown color. In the brewing of this liquor was this noise made which we thought strange; for the pressing of this gourd gently down into the liquor, and the air which it contained being forced out of the little hole at top occasioned a sound; and according to the time and motion given would be various. This drink when made, and cooled to sup, was in a conch-shell first carried to the Casseekey, who threw part of it on the ground, and the rest he drank up, and then would make a loud He-m; and afterwards the cup passed to the rest of the Casseekey’s associates, as aforesaid, but no other man, woman nor child must touch or taste of this sort of drink; of which they sat sipping, chatting and smoking tobacco, or some other herb instead thereof, for the most part of the day.

About noon was some fish brought us on small palmetto leaves, being boiled with scales, head and gills, and nothing taken from them but the guts; but our troubles and exercise were such that we cared not for food.

In the evening, we being laid on the place aforesaid the Indians made a drum of a skin, covering therewith the deep bowl in which they brewed their drink, beating thereon with a stick, and having a couple of rattles made of a small gourd put on a stick with small stones in it, shaking it, they began to set up a most hideous howling, very irksome to us, and some time after came some of their young women, some singing, some dancing. This was continued till midnight, after which they went to sleep.

The 8 month, 1; the 5 day of the week.

This day the Casseekey looking on us pleasantly, made presents to some of us, especially to my wife; he gave her a parcel of shellfish, which are known by the name of clams; one or two he roasted and gave her, showing that she must serve the rest SO, and eat them. The Indian women would take our child and suckle it, for its mother’s milk was almost gone that it could not get a meal: and our child, which had been at death’s door from the time of its birth until we were cast away, began now to be cheerful, and have an appetite to food. It had no covering but a small piece of raw deer skin; not a shred of linen or woollen to put on it.

About the tenth hour we observed the Indians to be on a sudden motion, most of the principal of them betook themselves to their houses: the Casseekey went to dressing his head and painting himself, and so also did the rest. When they had done, they came into the Casseekey’s house, and seated themselves in order. In a small time after came an Indian with some small attendance into the house, making a ceremonious motion, and seated himself by the Casseekey, the persons that came with him seated themselves amongst the others. After some small pause the Casseekey began a discourse, which held nigh an hour. After which the strange Indian and his companions went forth to the waterside, unto their canoe lying in the sound, and returned presently with such presents as they had brought, delivering them unto the Casseekey, and those sitting by giving an applause. The presents were some few bunches of the herb they make their drink of, and another herb which they use instead of tobacco, and some platted balls stuffed with moss to lay their heads on instead of pillows. The ceremony being ended, they all seated themselves again, and went to drinking casseena, smoking and talking during the strangers’ stay.

About noon some fish was brought us: hunger was grown strong upon [us], and the quantity given was not much more than each a mouthful; which we ate. The Casseekey ordered the master Joseph Kirle, Solomon Cresson, my wife and me, to sit upon their cabin to eat our fish; and they gave us some of their berries to eat. We tasted them, but not one amongst us could suffer them to stay in our mouths; for we could compare the taste of them to nothing else, but rotten cheese steeped in tobacco. Some time after we had eaten, some of the Indians asked us, if we were Spaniards. Solomon answered them, yes. Then some of the Indians would point to those whose hair was black, or of a deep brown, and say such a one was a Spaniard of the Havana, and such of Augustine: but those whose hair was of a light color they were doubtful of; some would say they were no Spaniards.

About the third hour in the afternoon the strangers went away, and some small time after they having satisfied themselves that most of us were Spaniards, told us that we should be sent for to the next town; and they told us that there was a Nickaleer off, and we understood them “Englishmen off Bristol,” also the number six men and a woman: and that they were to be put to death before we should get thither. We were silent, although much concerned to hear that report. They also told us that a messenger would come for us to direct us to the next town, thence to Augustine.

Night coming on they betook themselves to their accustomed singing and dancing. About the tenth or twelfth hour in the night before the singing and dancing was ended, came in a stranger armed with bow and arrows: the Casseekey and his companions entertained him with half an hour’s discourse, which ended, we were on a sudden ordered to get up and hurried away with this stranger, they not giving us time to see if we were all together; and a troop of young Indian men and boys followed us for about four miles, all which way they pelted us with stones; at length they all left us except two and our guide; but we missed Solomon Cresson, and Joseph Kirle’s boy, and Negro Ben; which was no small trouble to us.

We had not traveled above five miles before our guide caused to stop; and at some small distance was an Indian town, which I suppose our guide belonged to. Four Indians came thence with fire and water for him, and with palmetto leaves they made a blast of fire. Here we stayed nigh two hours: the flies were very thick and the night very cold, so that our naked bodies were not able to endure it but with grief. At length we left this place; the whole night following were troubled with these two young Indians, who at times would be abusing one or other of us, singling them out and asking if they were not Nickaleer or English? If they said, nay, then they would hit them a blow or more with a truncheon, which they had; and said, they were. We traveled all night without stopping from the aforesaid place.