James Adair’s biographical data is ambiguous at best and mostly non-existent. It is speculated he was born around 1709, in Antrim, Ireland. By the 1730s, Adair lived and traded with the Catawba in 1735; however, the Catawba’s struggles with alcohol and pressure from neighboring indigenous communities minimized their trading power. Adair moved farther west, solidifying relationships with the Cherokee in 1736. With the French in Louisiana and the Spanish in Florida straining English Carolinian trade and threatening the existence of the colony, South Carolina’s governor, William Bull, engaged Adair around 1738 to encourage the Chickasaw to settle in New Windsor on the Savannah River to fortify the colony’s defenses. After decades among the Chickasaw, Adair came to refer to himself as an “English Chickasaw” and “English Warrior.”

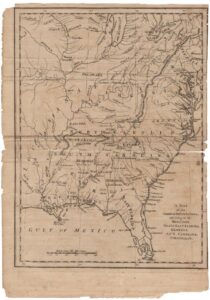

Map contained and referenced in Adair’s A History of the American Indians (courtesy, North Carolina Maps, State Library of North Carolina).

Adair claims he resided and transacted with Native American communities in the Southeast United States for four decades. During this time, he also participated in South Carolina’s political scene. However, A History of the American Indians (1775) established his legacy. Published in London on the eve of revolution and categorized as an “ethnohistory,” Adair’s text argues that Native Americans descended from Jews and were a lost “tribe of Israel.” The argument represented a form of colonial “othering” that began with the arrival of the Spanish in the Americas. Spain, and later, England, used these arguments to elevate their status over indigenous populations to justify imperial endeavors of genocide and property theft. Sources say that the argument lasted into the seventeenth century, but as Adair’s text shows, they continued to nearly the nineteenth century, at least. It is clear in reading Adair’s text that he found and curated facts to prove his point, not to investigate a hypothesis without bias. Notably, Adair had connections with, and received endorsements from, some of the most prominent politicians of the time, including Benjamin Franklin.

The excerpts below lie within the nearly four hundred pages that comprise Adair’s text and highlight Adair’s specific observations of Florida (divided into East and West Florida at the time of Adair’s writing) and its indigenous inhabitants in the 1700s. This selection does not include portions of Adair’s work equating Native Americans with Jews for the problematic reasons noted above and because these arguments do not substantially address Florida’s Native American populations. It does, however, include a discussion of cannibalism, mostly debunking the argument that Native American societies, or some of them, were cannibals, because this is not a common colonial position and because the excerpt directly addresses indigenous populations of “Cape-Florida” and their interactions with Muskogee society. This discussion includes references to “Cape-Florida Indian” rituals of eating human hearts and drinking from human skulls, but the editor does not endorse Adair’s viewpoints by including them here and cautions that: (1) Adair may have misinterpreted his observations; or (2) Adair may be engaging in another form of “othering” in his text.

It is estimated James Adair died circa 1783 in North Carolina.

All spellings, punctuation, and grammatical styles, including the spellings of names of Native American societies, are as found in the original text.

Edited by Jerry L. Rumph, Jr., University of South Florida

Further Reading

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians, Particularly Those Nations adjoining to the Mississippi, East and West Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, and Virginia: Containing an Account of their Origin, Language, Manners, Religious and Civil Customs, Laws, Form of Government, Punishments, Conduct in War and Domestic Life, Their Habits, Diet, Agriculture, Manufactures, Diseases and Method of Cure, and Other Particulars, sufficient to render it a Complete Indian System. With Observations of former Historians, the Conduct of our Colony Governors, Superintendents, Missionaries, &C. Also an Appendix, Containing a Description of the Floridas, and the Mississippi Lands, with their Productions—The Benefits of Colonising Georgiana, and civilizing the Indians—and the way to make all the Colonies more valuable to the Mother Country. With a new Map of the Country referred to in the History, edited by Kathryn E. Holland Braund. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Hudson, Charles. “James Adair as Anthropologist.” Ethnohistory 24: 4 (1977): 311–28.

Jowit, Claire. “Radical Identities? Native Americans, Jews, and the English Commonwealth.” The Seventeenth Century 10:1 (1995): 101-19.

Smith, Maud Thomas. “Adair, James Robert” (1979).

There is not the least trace among their ancient traditions, of their deserving the hateful name of cannibals, as our credulous writers have carefully copied from each other. Their taste is so opposite to that of the Anthrophagi, that they always over-dress their meat whether roasted or boiled.

The Muskoghe who have been at war, time out of mind, against the Indians of Cape-Florida, and at length reduced them to thirty men, who removed to the Havannah along with the Spaniards; affirm, they could never be informed by their captives, of the least inclination they ever had of eating human flesh, only the heart of the enemy—which they all do, sympathetically (blood for blood) in order to inspire them with courage; and yet the constant losses they suffered, might have highly provoked them to exceed their natural barbarity. To eat the heart of an enemy will in their opinion, like eating other things, before mentioned, communicate and give greater heart against the enemy. They also think that the vigorous faculties of the mind are derived from the brain, on which account, I have seen some of their heroes drink out of a human skull; they imagine, they only imbibe the good qualities it formerly contained.

When speaking to the Archimagus[1] concerning the Hottentots, those heterogeneous animals according to the Portuguese and Dutch accounts, he asked me, whether they builded and planted—and what sort of food they chiefly lived upon. I told him, I was informed that they dwelt in small nasty huts, and lived chiefly on sheep’s guts and crickets. He laughed, and said there was no credit to be given to the far-distant writers of those old books, because they might not have understood the language and customs of the people; but that those, whom our books reported to live on such nasty food, (if they did not deceive us) might have been forced to it for the want of better, to keep them from dying; or by the like occasion, they might have learned that ugly custom, and could not quit it when they were free from want, as the Choktah eat horse-flesh, though they have plenty of venison

[.…]

As this branch of the general subject cannot be illustrated but by well-known facts, I shall exemplify it with the late and long-continued conduct of the northern Indians, and those of Cape Florida, whom our navigators have reported to be cannibals. The Muskohge, who have been bitter enemies to the Cape Florida Indians, time immemorial, affirm their manners, tempers and appetites, to be the very same as those of the neighboring Indian nations. And the Florida captives who were sold in Carolina, have told me, that the Spaniards of St. Augustine and St. Mark’s garrisons, not only hired and paid them for murdering our seamen, who were so unfortunate as to be shipwrecked on their dangerous coast, but that they delivered up to the savages of our people they did not like, to be put to the fiery torture. From their bigoted persecuting spirit, we may conclude the victims to have been those who would not worship their images and crucifixes. The Spaniards no doubt could easily influence this decayed small tribe to such a practice, as they depended upon them for the necessaries of life: and though they could never settle out of their garrisons in West-Florida, on account of the jealous temper of the neighboring unconquered Indians, yet the Cape-Floridans were only Spanish mercenaries, shedding blood for their maintenance. A seduced Indian is certainly less faulty than the apostate Christian who instigated him; when an Indian sheds human blood, it does not proceed from wantonness, or the view of doing evil, but solely to put the law of retaliation in force, to return one injury for another; but, if he has received no ill, and has no suspicion of the kind, he usually offers no damage to those who fall in his power, but is moved with compassion, in proportion to what they seem to have undergone. Such as they devote to the fire, they flatter with the hope of being redeemed, as long as they can, to prevent the giving them any previous anxiety or grief, which their law of blood does not require.

Though the lands of West-Florida, for a considerable distance from the sea-shore, are very low, sour, wet, and unhealthy, yet it abounds with valuable timber for ship-building, which could not well be expended in the long space of many centuries. This is a very material article to so great a maritime power, as Great Britain, especially as it can be got with little expence and trouble. The French were said to deal pretty much that way; and the Spaniards, it is likely, will now resume it, as the bounty of our late ministry has allowed the French to transfer New-Orleans to them, and by that means they are able to disturb the British colonies at pleasure. It cannot fail of proving a constant bone of contention: a few troops could soon have taken it during the late war, for it was incapable of making any considerable resistance…. If it be allowed that the first discoverers and possessors of a foreign waste country, have a just title to it, the French by giving up New Orleans to Great Britain, would have only ceded to her, possessions, which they had no right to keep; for Col. Wood was the first discoverer of the Mississippi,[2] who stands on public record, and the chief part of ten years he employed in searching its course. This spirited attempt he began in the year 1654, and ended 1664…. [W]hereas the French did not discover it till the year 1699, when they gave it the name of Colbert’s-river, in honour of their favourite minister, and the whole country they called Louisiana, which may soon be exchanged for Philippiana—till the Americans give it another and more desirable name.

[.…]

If British subjects could settle West-Florida in security, it would in a few years become very valuable to Great Britain: and they would soon have as much profit, as they could desire, to reward their labour. Here, five hundred families would in all probability, be more beneficial to our mother-country, than the whole colony of North Carolina: besides innumerable branches toward Ohio and Monongahela….

As all the Florida Indians are grown jealous of us, since we settled E. and W. Florida, and are unacquainted with the great power of the Spaniards in South America, and have the French to polish their rough Indian politics, Louisiana is likely to prove more beneficial to them, than it did to the French….

From North-Carolina to the Mississippi, the land near the sea, is, in general, low and sandy; and it is very much so in the two colonies of Florida, to a considerable extent from the sea-shore, when the lands appear fertile, level, and diversified with hills. Trees indicate the goodness or badness of land. Pine-trees grow on sandy, barren ground, which produces long coarse grass; the adjacent low lands abound with canes, reads, or bay and laurel of various sorts, which are shaded with large expanding trees—they compose an evergreen thicket, mostly impenetrable to the beams of the sun, where the horses, deer, and cattle, chiefly feed during the winter: and the panthers, bears, wolves, wild cats, and foxes resort there, both for the sake of prey, and a cover from the hunters.

[….]

Any European state, except Great Britain, would at once improve their acquisitions, taken and purchased by an immense quantity of blood and treasure, and turn them to the public benefit. At the end of the late war, the ministry, and their adherents, held up East and West Florida before ethe eyes of the public, as greatly superior to those West-India islands, which Spain and France were to receive back in exchange. The islands however are rich, and annually add to the wealth and strength of those respective powers: while East Florida, is the only place of that extensive and valuable tract ceded to us, that we have any way improved; and this is little more than a negative good to our other colonies, in preventing their negroes from sheltering in that dreary country, under the protection of Fort St. Augustine. The province is a large peninsula, consisting chiefly of sandy barrens; level sour ground, abounding with tussucks; here and there is some light mixt land; but a number of low swamps, with very unwholesome water in general. In proportion as it is cleared, and a free circulation of air is produced, to dispel the noxious vapours that float over the surface of this low country, it may become more healthful; though any where out of the influence of the sea air, the inhabitants will be liable to fevers and agues. The favourable accounts of our military officers gave of the pure wholesome air of St. Augustine, are very just, when they compare it with the sand burning Pensacola and the lower stagnated Mobille: St. Augustine stands on a pleasant hill, at the conflux of two salt water rivers, overlooking the land from three angles of the castle, and down the sound, to the ocean. Their relation of the natural advantages of this country, could extend no farther than their marches reached. I formerly went volunteer, about six hundred miles through the country, with a great body of Indians against this place; and we ranged the woods to a great extent. The tracts we did not reach, we got full information of, by several of the Muskohge then with us, who had a thorough knowledge, on account of the long continued excursions they made through the country in quest of the Florida Indians; and even after they drove them into the islands of Florida, to live on fish, among clouds of musketoes. The method these Indians took to keep off those tormenting insects, as their safety would not allow them to make a fire, lest the smoke should guide their watchful enemies to surprise them, was, by anointing their bodies with rank fish oil, mixed with the juice or ashes of indigo. This perfume, and its effluvia, kept off from them every kind of insect. The Indians likewise informed me, that when they went to war against the Floridians, they carried their cypress bark canoes from the head of St. John’s black river, only about half a mile, when they launched them again into a deep river, which led down to a multitude of islands to the N.W. of Cape Florida.

As this colony is incontestably much better situated for trade than West Florida, or the Mississippi lands, it is surprising that Britain does not improve the opportunity which offers, by adding to these unhealthy low grounds a sufficient quantity of waste high land to enable the settlers, and their families, to raise those staples she wants. The Muskohge who claim it, might be offered, and they would accept, what it seems to be worth in its wild state. Justice to ourselves and neighbours, condemns the shortening the planter’s days, by confining their industrious families to unhealthy low lands, when nature invites them to come out, to enjoy her bountiful gifts of health and wealth, where only savage beasts prey on one another, and the bloodier two-footed savages, ramble about to prey on them, or whatsoever falls in their way. Under these, and other pressing circumstances of a similar nature, does this part of America now labour… As most of these colonies abound with frugal and industrious people, who are increasing very fast, and every year crowding more closely together on exhausted land, our rulers ought not to allow so mischievous and dangerous a body as the Muskohge to ingross this vast forest, mostly for wild beasts. This haughty nation is directly in the way of our valuable southern colonies, and will check them from rising to half the height of perfection, which the favourableness of the soil and climate allow, unless we give them sever correction, or drive them over the Mississippi, the first time they renew their acts of hostility against us, without sufficient retaliation. At present, West Florida is nothing but an expence to the public.—The name amuses indeed, at a distance; but were it duly extended and settled, it would become very valuable to Great Britain; and Pensacola harbour would be then serviceable also in a time of war with Spain, being in the gulph of Florida, and near to Cuba. Mobille is a black trifle. Its garrison, and that at Pensacola, cannot be properly supplied by their French neighbours though at a most exorbitant price: and, on account of our own passive conduct, the Msukohge will not allow the inhabitants of Georgia to drive cattle to those places for the use of the soldiers. Neither can the northern merchant-men supply them with salt and fresh provisions, but at a very unequal hazard; for the gulph stream would oblige them to sail along the Cuba shore, where they would be likely to be seized by the Spanish guarda costas, as have many fine American vessels on the false pretence of smuggling, and which, by a strange kind of policy, they have been allowed to keep as legal prizes. In brief, unless Great Britain enlarges both East and West Florida to a proper extent, and adopts other encouraging measures, for raising those staple commodities which she purchases from foreigners, the sagacious public must be convinced, that the opportunity of adding to her annual expences, by paying troops, and maintaining garrisons, to guard a narrow slip of barren sand=hills, and a tract of low grave-yards, is not an equivalent for those valuable improved islands our enemies received in exchange for them….

The two Floridas, and this, which to the great loss of the nation, lie shamefully neglected, are the only places in the British empire, from whence she can receive a sufficient supply of those staples she wants. The prosperity, and even the welfare of Great Britain, depends on sundry accounts, in a high degree, on improving these valuable and dear bought acquisitions; and we hope her eyes will be opened soon, and her hands stretched out to do it—she will provide for the necessities of her own poor at home, by the very means that would employ a multitude of useless people in agriculture here, and bring the savages into a probably way of being civilized, and becoming christians, by contracting their circle of three thousand miles, and turning them from a lonely hunt of wild beasts, to the various good purposes of society. Should Great Britain duly exert herself as the value of this place requires, by the assistance of our old Chikkasah allies, the other Indian nations would be forced to pursue their true interest, by living peaceably with us; and be soon enticed to become very serviceable both to our planters, and the enlargement of trade….

The prodigious number of fertile hills lying near some of the large streams, and among the numberless smaller branches of the Mississippi, from 33 to 37 degrees N.L. (and likewise in the two Floridas) are well adapted by nature, for producing different sorts of wine, as any place whatever. The high lands naturally abound with a variety of wine grapes: if therefore these extensive lands were settled, and planters met with due encouragement, Great Britain in a few years might purchase here, with her own manufacturers, a sufficient supply of as good wines as she buys from her dangerous rival France, at a great disadvantage of trade, or even from Portugal….

I am well acquainted with near two thousand miles along the American continent, and have frequently been in the remote woods; but the quantity of fertile lands, in all that vast space, exclusive of what ought to be added to East and West-Florida, seems to bear only a small proportion to those between the Mississippi and Mobille-river, with its N. W. branches, which run about thirty miles north of the Chikkasah country, and intermix with pleasant branches of the great Cheerake river. In settling the two Floridas, and the Mississippi-lands, administration should not suffer them to be monopolized—nor the people to be classed and treated as slaves—Let them have a constitutional form of government, the inhabitants will be cheerful, and every thing will be prosperous. The country promises to yield as plentiful harvests of the most valuable productions as can be wished.

[1] Medicine person or magician.

[2] The terminology of discovery is original to the text. The editor acknowledges that indigenous persons populated the North American continent, including the area of the Mississippi River, for thousands of years prior to Colonel Wood’s arrival.