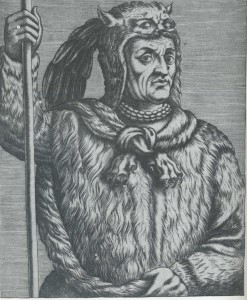

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues (1533-1588), illustrator and cartographer, accompanied Rene de Laudonniere’s ill-fated attempt to colonize Florida in 1564. The first European artist to reach Florida, Le Moyne charted the St. John’s Bluff region, now Jacksonville, and sketched scenes from the lives of the Timucua Indians. Le Moyne lost most of his work during the 1565 Spanish attack on Fort Caroline. One of the few French survivors returning to France in 1566, he redrew his sketches and recounted his Florida  experience to the King of France, Charles IX. Le Moyne’s illustrations and narrative are of vital historical importance, being some of the earliest visual evidence to accompany a narrative of the sixteenth-century Florida expeditions.

experience to the King of France, Charles IX. Le Moyne’s illustrations and narrative are of vital historical importance, being some of the earliest visual evidence to accompany a narrative of the sixteenth-century Florida expeditions.

Despite the historical significance, controversy surrounds Le Moyne’s work. Original details may have been lost, or scenes may have been embellished, since Le Moyne redrew most of his images from memory. In 1591, Theodor de Bry made 42 engravings from Le Moyne’s drawings compiling these images and Le Moyne’s narrative into a book. Scholars today question the authenticity of the engravings. Many details do not match Indian culture artists later sketched in the New World, fauna indigenous to Florida or artifacts archaeologists found in regional excavations suggesting either Le Moyne or de Bry had incorporated details known from other parts of the world such as South America. Only one of Le Moyne’s original paintings, in the New York Public Library, survives today. This remaining piece is also in question as scholars debate whether this painting is a Le Moyne original or also a replica.

Edited by Valerie Lanham, University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Further Reading

Birch, Sally. “Through an Artist’s Eye: Observations on Aspects of Copying in Two Groups of Work by John White c. 1585-90.” European Visions: American Voices. London: British Museum Press, 2009. 85-96.

Fishman, Laura. “Old World Images Encounter New World Reality: Rene Laudonniere and the Timucuans of Florida.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 26: 3 (Autumn 1995): 547-559. Print.

Lorant, Stefan (ed.). The New World: The First Pictures of America.New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1946. Print.

Harvey, Miles. Painter in a Savage Land: The Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America. New York: Random House 2008.

Le Moyne de Morgues, Jacques. John H. Levine Collection, New York Public Library Digital Gallery:New York. “Laudonnierus et rex athore ante columnam a praefecto prima navigatione locatam quamque venerantur floridenses”

Milanich, Jerald. “The Devil in the Details — Jacques LeMoyne, Images of the Engravings.” Archaeology. May-June 2005. 27–31.

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues. Narrative of Le Moyne, An Artist who Accompanied the French Expedition to Florida under Laudonnière, 1564. Transl. Transl. Fred B. Perkins. (Boston: Osgood, 1875).

Charles IX, King of France, having been notified by the Admiral de Châtillon that there was too much delay in sending forward the reinforcements needed by the small body of French whom Jean Ribaud had left to maintain the French dominion in Florida, gave orders to the admiral to fit out such a fleet as was required for the purpose. The admiral, in the meanwhile, recommended to the king a nobleman of the name of Renaud de Laudonnière; a person well known at court, and of varied abilities, though experienced not so much in military as in naval affairs. The king accordingly appointed him his own lieutenant, and appropriated for the expedition the sum of a hundred thousand francs. The admiral, who was a man endowed with all the virtues, and eminent for Christian piety, was so zealous for the faithful doing of the king’s business, as to give special instructions to Laudonnière, exhorting him in particular to use all manner of diligence in doing his duty, and first of all, since he professed to be a religious man, to select the right sort of men, and such as feared God, to be of his company. He would do well, in the next place, to engage as many skilled mechanics of all kinds as possible. In order to give him better facilities for these purposes he received a royal commission, bearing the king’s seal.

Laudonnière accordingly repaired to Havre de Grace, where he proceeded to get his ships ready, and, according to his orders, with the greatest diligence sought out good men all over the kingdom; so that I can safely assert that men of remarkable skill in all sorts of mechanical employments resorted to him. There also assembled a number of nobles, youths of ancient families, drawn only by the desire of viewing foreign countries; for they asked no pay, volunteering for the expedition at their own cost and charges. The soldiers were chosen veterans, every man competent to act as an officer in time of battle. From Dieppe were obtained the two best navigators of our times, Michael le Vasseur and his brother Thomas le Vasseur, both of whom were employed in the king’s naval service. I also received orders to join the expedition, and to report to M. de Laudonnière.

All who came he received with courtesy and with magnificent promises. As, however, I was not unaware that the gentlemen of the court are, in the habit of being liberal with their promises, I asked for some positive statements of his own views, and of the particular object which the king desired to obtain in commanding my services. Upon this he promised that no services except honorable ones should be required of me; and he informed me that my special duty, when we should reach the Indies, would be to map the seacoast, and lay down the position of towns, the depth and course of rivers, and the harbors; and to represent also the dwellings of the natives, and whatever in the province might seem worthy of observation: all of which I performed to the best of my ability, as I showed his majesty, when, after having escaped from the remarkable perfidies and atrocious cruelties of the Spaniards, I returned to France.

On the 20th April, 1564, our three ships set sail from Havre de Grace, and steered direct for the Fortunate Islands, or, as seafaring men call them, the Canaries. Sailing thence, on the tropic we made the Antilles Islands, at one of which, called Dominica, we watered, losing, however, two men. Making sail again, we reached the coast of Florida, or New France as it is called, on Thursday, 22d June.

M. de Laudonnière having reconnoitered the stream named by Ribaud the River of May, and finding it of easy navigation for ships, and offering a suitable place for a fort, set promptly about preparing to erect one, and sent back to France his largest ship, the Elizabeth of Honfleur, commanded by Jean Lucas. Meanwhile all the seashore was occupied by immense numbers of men and women, who kept up fires, and against whom we naturally thought it necessary to be much on our guard. Gradually, however, it appeared that to injure us was the last thing in their thoughts: on the other hand, they showed numerous testimonies of friendship and liking, being seized with great admiration at finding our flesh so different from theirs in softness and tenderness, and our garments so different from their own. The commodities which we received from these new dealers were in great part such things as they value most, being for the support of life or the protection of the body. Such were grains of maize roasted, or ground into flour, or whole ears of it; smoked lizards or other wild animals, such as they consider great delicacies; and various kinds of roots, some for food, and some for medicine. When they found out after a time that the French were more desirous of metals and minerals, some brought them. M. de Laudonnière, who soon perceived that our men were acting avariciously in their dealing, now forbade, on pain of death, any trading or exchange with the Indians for gold, silver, or minerals, unless all such should be put into a common stock for the benefit of all.

In the meantime several chiefs visited our commander, and signified to him that they were under the authority of a certain king named Saturioua, within the limits of whose dominions we were, whose dwelling was near us, and who could muster a force of some thousands of men. This information was thought good reason for hastening the completion of our fort. King Saturioua himself, on his part, like a prudent commander, sent out his scouts from day to day, to see what we were about; and being advised by them that we had marked out a triangle by stretching cords, and were digging up the earth on the lines of it, he became desirous of seeing for himself. He sent forward, however, some two hours in advance of his own appearance, an officer with a company of a hundred and twenty able-bodied men, armed with bows, arrows, clubs, and darts, and adorned, after the Indian manner, with their riches; such as feathers of different kinds, necklaces of a select sort of shells, bracelets of fishes’ teeth, girdles of silver-colored balls, some round and some oblong; and having many pearls fastened on their legs. Many of them had also hanging to their legs round flat plates of gold, silver, or brass, so that in walking they tinkled like little bells. This officer, having made his announcement, proceeded to cause shelter to be erected on a small height nearby, of branches of palms, laurels, mastics, and other odoriferous trees, for the accommodation of the king. From this point the king could see whatever was going on within our lines, and a few tents and military supplies and baggage, which we had not yet found time to get under cover; as our first business was to get our fort completed, rather than to put up huts, which could be easily erected more at leisure afterwards.

M. de Laudonnière, upon receiving the message of the officer, so disposed his force as to be prepared for a stout resistance in case of attack, although they had no ammunition on shore for their defense. In the next place, as he had himself while with Ribaud on a former occasion stopped here, and seen this same chief, had learned a few words of his language, and knew the ceremonial with which he expected to be received; and as one of his men, an intelligent and active person, who had also been here with Ribaud, and was now a captain, possessed the same information, — M. de Laudonnière decided that it would be best for none to approach the king’s presence except himself, M. d’Ottigny his second in command, and Capt. La Caille just referred to.

The king was accompanied by seven or eight hundred men, handsome, strong, well-made, and active fellows, the best-trained and swiftest of his force, all under arms as if on a military expedition. Before him marched fifty youths with javelins or spears; and behind these, and next to himself, were twenty pipers, who produced a wild noise, without musical harmony or regularity, but only blowing away with all their might, each trying to be the loudest. Their instruments were nothing but a thick sort of reeds, or canes, with two openings; one at the top to blow into, and the other at the other end for the wind to come out of, like organ-pipes or whistles. On his right hand limped his soothsayer, and on the left was his chief counselor; without which two personages he never proceeded on any matter whatever. He entered the place prepared for him alone, and sat down in it after the Indian manner; that is, by squatting on the ground like an ape or any other animal. Then having looked all around, and having observed our little force drawn up in line of battle, he ordered MM. de Laudonnière and D’Ottigny to be invited into his tabernacle, where he delivered to them a long oration, which they understood only in part. He did, however, inquire who we were, why we had landed on his territory rather than elsewhere, and what was our purpose. M. de Laudonnière replied by the mouth of Capt. La Caille, who, as was mentioned, had some knowledge of the language, that he was sent by a most powerful king, called the King of France, to offer a treaty by which he should become a friend to the king here, and to his allies, and an enemy to their enemies; an announcement which the chief received with much pleasure. Gifts were then exchanged in pledge of perpetual friendship and alliance. This done, the king approached nearer to our force, and greatly admired our arms, particularly the arquebuses. Upon coming up to the ditch of our fort, he took measurements both within and without; and perceiving that the earth was being taken from the ditch, and laid into a rampart, he asked what was the use of the operation. He was told in reply that we were going to put up a building that would hold all of us, and that many small houses were to be erected inside of it; at which he expressed admiration, and a desire to see it completed as soon as possible. To this end, he was therefore asked to give us the help of some of his followers in the work. He consented, and sent us eighty of his stoutest men, most used to labor, who were of great assistance to us, and much hastened the completion both of our fort and cabins. Having given his orders about this, he himself went away.

While all this was going on, every man of our force—noblemen, soldiers, artificers, sailors, and all—was hard at work to get our post in a state of defense against an enemy, and to get up a shelter from the weather; and every man was making sure, from the amount of the gifts and trading so far, that he would quickly become rich.

The fort being now completed, and a residence for himself, as well as a large building to contain the provisions and other indispensable military supplies, M. de Laudonnière proceeded to shorten the allowance of food and drink: so that, after three weeks, only one glass of spirit and water, half and half, was given out daily per man; and as for provisions, which it had been hoped would be abundant in this New World, none at all were found; and, unless the natives had furnished us from their own stores from day to day, some of us must assuredly have perished from starvation, especially such as did not know how to use fire-arms in hunting.

In the mean while M. de Laudonnière ordered his chief artificer, Jean des Hayes of Dieppe, to build two shallops, to be, according to my recollection, of thirty-five or forty feet keel, for exploring in the upper waters of the river, and along the seacoast; which were in good season nearly completed.

But by this time the noblemen who had come from France to the New World from ambitious motives only, and with splendid outfits, began to be greatly dissatisfied at finding that they realized none of the advantages which they had imagined, and promised themselves; and complaints began daily to be made by many of them. On the other part M. de Laudonnière himself, who was a man too easily influenced by others, evidently fell into the hands of three or four parasites, and treated with contempt the soldiers, who were just those whom he should have most considered. And, what is far worse, indignation began to be felt by many who professed the desire of living according to the doctrine of the reformed gospel, for the reason that they found themselves without a minister of God’s word.

But, to return to King Saturioua. This chief sent messengers to M. de Laudonnière, not only to confirm the league which had been made, but also to procure the performance of its conditions, namely, that the latter was to be the friend of the king’s friends, and the enemy of his enemies; as he was now organizing an expedition against them. M. de Laudonnière gave an ambiguous reply to these ambassadors; for we had learned, in the course of an extended voyage up the main stream of the River of May, that the enemy of our neighbor King Saturioua was far more powerful than he; and that, more-over, his friendship was indispensable to, us for the reason that the road to the Apalatcy Mountains (which we were desirous of reaching, because we were informed that most of the gold and silver which we had received in trade was brought thence) lay through his dominions. Besides, some of our people were already with him, who had already sent to the fort a good deal of gold and silver, and were negotiating with him; for M. de Laudonnière had orders to treat with this great king, Outina, on the same terms as above mentioned.

King Saturioua, having received this cold answer, now came to the fort, which was called Fort Carolina, with some twelve or fifteen hundred men; but finding, to his surprise, that things were greatly changed, that he could no longer get across the ditch, but that there was only one entrance to the post, and that a very narrow one, he came thither, and found Capt. La Caille; who announced to him, that, for the purpose of an interview, he would not be admitted into the fort unless without his men, or at most with not more than twenty of such as he might select. In astonishment at this information, he, however, dissimulated, and entered the fort with twenty of his followers, when everything was exhibited to him. He was terribly frightened himself at the sound of the drums and trumpets, and at the reports of the brass cannon which were fired in his presence; and, when he was told that all his force had run away, he readily believed it, as he would gladly have been farther off himself. This, indeed, made our name great through all those parts; and, in fact, much more than the reality was believed of us. He did, however, after all, notify M. de Laudonnière that his faith was pledged, that his own (King Saturioua’s) forces were ready, that his supplies were at hand, and that his own subordinate chiefs were assembled. Failing, however, to obtain what he wished, he set out on his expedition with his own men.

While these affairs were in progress, M. de Laudonnière sent his second ship, commanded by Pierre Capitaine [Petrus Centurio], to France. And now let the reader be pleased to observe how many were those who sought to return home. Among others, one young nobleman, De Marillac by name, was so earnestly desirous of going, that he promised M. de Laudonnière, if the latter would send him back in charge of dispatches, to reveal to him matters of the utmost importance touching his life and good name; on condition, however, that the papers containing these revelations should not be opened until after he (Marillac) had embarked. M. de Laudonnière too credulously agreed to this proposition.

On the very day when the ship was to sail, a certain nobleman of the name of M. de Gièvre, of a good family, of the rank of count, one who feared God, and was liked by all, received warning, five or six hours before the time at which the information promised was to be put into the hands of M. de Laudonnière, that he would do well to escape, for that Marillac had laid a plot against him. He accordingly took refuge in the woods to shun the wrath of M. de Laudonnière, to whom Marillac had delivered some infamous libels written, as he asserted, in the hand of M. de Gièvre. Their purport was, that Laudonnière had made a wrongful use of the hundred thousand francs given him by the king, since he had brought no supply of provisions over with him; that he had not brought over, as the admiral directed him to do, a minister of God’s word; that he bestowed too much of his favor on tattlers and praters, but despised those of real merit; and many other things which I do not now remember.

This exile of M. de Gièvre was unwelcome to many good men, who, however, all kept silence. Gradually, however, some began to be dissatisfied with the bad provision of food, and others with the excess of labor required, and with its severity; particularly certain of the nobles, who considered that they should have been treated with more respect. After various interchange of opinions between individuals, secret consultations began to be held, at first by five or six persons only, but by more and more, until as many as thirty were engaged. But among the first who thus began to consult was one especial favorite of M. de Laudonnière; and it is absolutely certain that it was the very best of the soldiers and noblemen who were engaged in these consultations, and that these influenced the rest; passing over those whom they despised as deficient in shrewdness, and whom, therefore, they did not admit into their counsels.

At a proper time, they addressed themselves to Capt. La Caille, to whom the plan had so far not been revealed, because all knew him to be a man of integrity himself, and who would require the utmost loyalty in all matters of duty from others. Him they now besought, that, as he was the senior captain, he would interest himself in this matter, which concerned all, and that he would consent to deliver to M. de Laudonnière their written statement of their grievances. La Caille promised his assistance; and, as they had selected him to take charge of the matter, he resolved to communicate it to M. de Laudonnière in their name, even though the commander should choose to be displeased, and even though he should risk his own life in consequence; since he believed their petition a proper one. On the next day, which was the Lord’s Day, he went early to M. de Laudonnière’s house, and requested him, in the name of all the company, to come to the place of public assembly, where he (La Caille) wished to communicate to him a certain matter. All being assembled, M. de Laudonnière appeared with his second in command, M. d’Ottigny; and, silence being proclaimed, Capt. La Caille proceeded to speak as follows: —

“Sir, we all, who are here, in the first place protest that we recognize you as the lieutenant of the king, our supreme lord in this province, where our present settlement has been founded in his name; and that we will obey your orders in this very honorable expedition, even though for his majesty’s sake our lives shall be poured out before you, as you have already known by experiment in the case of great part of those who are here present, among whom are many of noble rank, who to the neglect of their own advantage have followed you as volunteers at their own expense. In the next place, they would now with all due respect remind you, that, before leaving France, pledges were given to each of them that provisions sufficient for one whole year should be brought over, and that additional supplies should be at hand before those were exhausted; while so far was this from being the case the provisions brought were scarcely one month’s supply.

“The Indians, after a time, began to be slow in bringing in supplies, because they found that most of us had no longer anything to give for them; and it is not unknown to you that these savages do not give anything without getting something for it. When after this they found that no commodities at all were forthcoming from any of us, and when the soldiers undertook to extort supplies from them by blows (as some of them began to do, to the great grief of the wiser among them), they deserted the whole neighborhood; so that we lost even those sources of supply which we had, and even with the continued aid of which we had nothing better to expect than the extremity of hunger. In order, there-fore, to remedy these difficulties, those present most urgently beseech you to cause the third of the ships which brought us from France, now lying in the river, to be repaired and fitted out; to man her with such persons as you may see fit; and to send her to New Spain, which is not far from this province, to obtain supplies by purchase or otherwise; not doubting that this measure will relieve us. Or, if any better measures shall be suggested, they are ready to acquiesce in them.” This was the substance of the address at this assembly.

M. de Laudonnière’s reply was brief: that they had no title to require an account from him of his actions; that, as to supplies, he would provide for them, as he still had several casks full of merchandise which he would put into the common stock in order that they might trade with the Indians for provisions; that, as to sending to New Spain, he never would do it; but that instead he would let them take the two shallops that had been begun, for coasting-voyages within two or three hundred miles, by which they would be able to collect provisions enough and to spare. With this reply, the assembly was dismissed.

M. de Laudonnière had been sending out men to explore the remoter parts of the country, more particularly those in the vicinity of the great King Outina, the enemy of our own neighbor, and from whom, by the channel of some of our Frenchmen who had got into relations with him, a good deal of gold and silver had been sent to the fort, as well as pearls, and other valuable articles. But this duty was not allotted to everybody; and, as those employed on it were supposed to be growing rich very fast, many began to be envious of them; and, although M. de Laudonnière promised that everything should be distributed equally to all, many were dissatisfied. For there was one La Roche Ferrière, who being a talkative person, and pretending to know every thing, had become so influential with M. de Laudonnière, as to be considered by him almost an oracle. I do not deny that he was a man of ability, and eminently useful in establishing this new acquisition of ours, or that it was due to his continued influence with the King Outina that the commodities referred to were sent into the fort. In return, five or six arquebusiers were sent to him, to be employed in one direction or another, as the occasions or necessities of himself or Outina might require. But, in brief, his operations resulted in Outina’s making peace with some enemies of his near the mountains. With reference to this matter, he wrote to M. de Laudonnière to send someone to take his place, as he had various important affairs to communicate touching the king’s service, and the honor and advantage of all.

Upon this, M. dc Laudonnière at once sent out a person to take the place of La. Roche Ferrière; who returned to the fort reporting that he had certain information that all the gold and silver which had been sent to it came from the Apalatcy Mountains, and that the Indians from whom he obtained it knew of no other place to get it, since they had got all they had had so far in warring with three chiefs, named Potanou, Onatheaqua, and Oustaca, who had been preventing the great chief Outina from taking possession of these mountains. Moreover, La Roche Ferrière brought with him a piece of rock mined in those mountains, containing a sufficiently good display of gold and brass. He therefore requested permission of M. de Laudonnière to undertake the long journey by which he hoped he could reach these three chiefs, and examine the state of things about them. Having accordingly received permission, he set out.

La Roche Ferrière having gone, the thirty who got up the demonstration or supplicatory paper above referred to throw everything into disorder in the fort, of which they determined to take possession in order to effect a change in the conduct of affairs. As the best mode of proceeding, they chose as leaders one M. de Fourneaux, a great hypocrite, and excessively avaricious; one Stephen of Genoa, an Italian; and a third named La Croix: and of the soldiers a captain named Seignore, a Gascon. They then brought over to their way of thinking all the military officers except three: namely, M. d’Ottigny, the second in command; M. d’Arlac, the ensign, a Swiss gentleman; and Capt. La Caille. The rest of the soldiers they so effectually prevailed with, that sixty-six of them, being the best veteran men, joined them. They tried also to corrupt me, through some of my intimate friends, by showing me the list of names of those who had joined, and threatening terrible things against those who should not do the same. I, however, requested them not to trouble me further, as I was against them in this matter. M. de Laudonnière knew that some conspiracy was forming, but he did not know by whom. Some things also had come to the knowledge of M. d’Ottigny, but very obscurely. On the evening of the night during which the conspirators had decided to put their plan into execution, I was informed by a Norman gentleman named De Pompierre that they had resolved that night to cut the throat of Capt. La Caille, whose lodging and mine were the same; and that, if I valued my life, I had better be out of the way. As, however, the time was too short to allow me to make the necessary arrangements, I went home, and told La Caille what I had heard. He at once fled by a rear door, and hid himself in the woods; while I thought it best to recommend myself to the protection of God, and to await the event.

At midnight Fourneaux, the chief of the conspirators, armed with his cuirass, and carrying an arquebuse in his hand, and having twenty arquebusiers along with him, went to M. de Laudonnière’s house, which he commanded to be opened; and, going straight to his bedside, put his weapon to his throat, and, assailing him with the vilest insults, seized the keys of the armory and storehouse, took away all his weapons, and, having put fetters on his feet, ordered him to be confined as a prisoner on the ship which lay in the river opposite the fort, under a guard of two soldiers. At the same time La Croix the other leader, also armed, and with fifteen men, entered the lodging of M. d’Ottigny, whom, however, they did not otherwise injure than to take away his arms, and forbid him, on pain of death, from leaving the house until daylight; which order he promised to obey. The same was done by Stephen the Genoese at the lodgings of the ensign, M. d’Arlac, who was obliged to take a similar oath. At the same time Capt. Seignore, with the rest of the soldiers who had joined the conspiracy, came to Capt. La Caille’s, intending to kill him because he had openly opposed their undertaking after they had informed him of it; but, though they sought everywhere, they could neither find him nor his two brothers. They, however, carried away all their arms, as they also did mine; and an order was given that I should be carried a prisoner to the soldiers’ quarters. At the intercession, however, of several gentlemen of high character, who, without any clear understanding of the affair, had been induced by others to go into it, my weapons were restored to me, on condition, however, that I should not leave the house until daylight; which I promised. He then went to the quarters of those soldiers who had not joined, and took possession of their arms; and thus the control of affairs was completely secured.

M. de Laudonnière being confined in chains as above related, his Lieutenant d’Ottigny, and his Ensign d’Arlac being disarmed and confined at home, Capt. La Caille being a wanderer among the wild beasts in the woods, and the rest of the true men being disarmed, the conspirators proceeded to upset the whole constitution of affairs, abusing, however, the name and authority of M. de Laudonnière, for the easier attaining of their objects. De Fourneaux, the chief of the conspiracy, caused a diploma or license to be drawn out on parchment, in the name of M. de Laudonnière, in which, as lieutenant of the king of France, he authorized the greater part of his force, in consequence of the scarcity of provisions, to proceed to New Spain to obtain supplies, and requesting all governors, captains, and others holding any office under the king of Spain, to aid them in this business. This document, which they themselves drafted, they forced M. de Laudonnière to sign. They then fitted out the two shallops that were before mentioned, taking the requisite armament and provisions from the king’s stores, and selected the pilots and crews for the voyage to New Spain. They made the old man Michael Le Vasseur of Dieppe pilot of one, appointing to the other one Trenchant; and, thus prepared, they set sail from Carolina on the 8th December, calling us cowards and green hands, and threatening that if, on their return from New Spain with the wealth they proposed to acquire, we should refuse to admit them into the fort, they would tread us under foot.

But, while these are in the pursuit of wealth by piracy, let us return to La Roche Ferrière, who, having reached the mountains, succeeded by prudence and assiduity in placing himself on a friendly footing with the three chiefs before mentioned, the most bitter enemies of King Outina. He was astonished at their civilization and opulence, and sent to M. de Laudonnière at the fort many gifts which they bestowed upon him. Among these were circular plates of gold and silver, as large as a moderate-sized platter, such as they are accustomed to wear to protect the back and breast in war; much gold alloyed with brass, and silver not thoroughly smelted. He sent also some quivers covered with very choice skins, with golden heads to all the arrows; and many pieces of a stuff made of feathers, and most skillfully ornamented with rushes of different colors; also green and blue stones, which some thought to be emeralds and sapphires, in the form of wedges, and which they used instead of axes, for cutting wood. M. de Laudonnière sent in return such commodities as he had, such as some thick rough cloths, a few axes and saws, and other cheap Parisian goods, with which they were perfectly satisfied.

By these dealings M. la Roche Ferrière brought himself into the worst possible odor with King Outina, and still more among his subordinate chiefs, who conceived such a hatred for him that they would not even call him by name, saying always, instead, “Timogua,” that is, Enemy. As long, however, as La Roche Ferrière preserved the friendship of the three chiefs, he was able to go to and from the fort by other roads, as there are many small streams which empty into the River of May for fifteen or sixteen miles below the territory of King Outina.

I believe I shall not depart too far from my story if I mention a certain soldier who was emulous of the example of La Roche Ferrière, and therefore demanded permission from M. de Laudonnière to trade in another quarter. He was given it, but was warned to consider well what he was about, as it was not impossible that his attempt to open a trade would cost him his life; which, indeed, is what actually happened. This soldier was named Pierre Gamble, and was a young, strong, and active man, who had from early youth been brought up in the home of the Admiral de Châtillon. Having received his permission, he departed alone, without any servant, from the fort, laden with a parcel of cheap goods, and with his arquebuse, and began to trade up and down the country. He was so successful in his management, that he even came to exercise a sort of authority over the natives, whom he used to make bring his messages to us. At length, having visited a certain inferior chief called Adelano, who lived on a small island in the river, he became so friendly with him, and so great a favorite, that the chief gave him his daughter to wife. Although thus honored, he continued his pursuit of gain. In the chief’s absence, he exercised authority in his stead, and did it so tyrannically, requiring the Indians to obtain for him things quite out of their power, that he made himself hated by all of them. But, as he was beloved by the chief, none ventured to complain. It happened at length, that he asked leave of the chief to make a visit to the fort, as he had not seen his friends there for twelve months. He received permission, but on condition that he should return in a few days. Having got together all his wealth, and embarked it in a canoe or skiff which was furnished him for the purpose, and with two Indians to paddle, he took leave of the chief. While on the journey, one of his companions recalled to mind that he had been, on a former occasion, beaten with sticks by this soldier; and, the booty now offering being an additional temptation, he concluded that so eligible an opportunity of securing at once revenge and plunder must not be missed. Accordingly, while the soldier was bending over a fire in complete security, the Indian seized an axe which lay next his victim, and split open his head. Then, seizing the goods, he and his companion fled.

I will now return to the liberation of M. de Laudonnière, and to the account of what took place after the departure of our men; who, by the way, had carried off with them certain half–casks of rich Spanish wine, which, as both M. de Laudonnière and his maid-servant asserted, had been put aside for the use of the sick. Capt. La Caille, who was wandering in the woods, learned from his younger brother, who had been acting as a messenger to keep him supplied with what his friends could furnish, of the departure of the men who had threatened his life, and at once came back to the fort. Here he set about encouraging the rest; exhorted all to take possession of their arms again (those who had gone not having had any use for them); and M. de Laudonnière was brought ashore from the ship, and his Lieutenant D’Ottigny and Ensign d’Arlac were safely let out of their homes. The muster-roll was called; all took oath anew, both of allegiance to the king, and of resistance to the enemy, in whose number those were now reckoned who had treated us so wickedly and contemptuously. Four captains were appointed; the whole company was divided into four companies under them, and so all returned to their regular duties.

While all this was taking place, there came to the fort a young gentleman of Poitiers, named De Groutaut, sent by M. La Roche Ferrière, one of whose companions he had always been, even during his expedition to the three kings near the Apalatcy Mountains. He brought word to M. de Laudonnière, that one of these three chiefs was taken with a great affection for the Christians; that he was powerful and wealthy, having always on foot a military force of four thousand men; and that he had requested M. La Roche Ferrière to signify to M. de Laudonnière that he offered to conclude a perpetual league with him; and that, as he understood that we were searching for gold, he would bind himself by any conditions we might require; that, if a hundred arquebusiers should be supplied him, he would certainly render them victorious masters of the Apalatcy Mountains. La Roche Ferrière, knowing nothing of the troubles at the fort, had promised that this should be arranged; nor is there any doubt that, had we not been so shamefully deserted by the greater part of our men, the experiment would have been tried, on the information of the remarkable liking which this chief had conceived for us. But M. de Laudonnière, considering that if he should send away a hundred men, he would not have force enough left to defend the post, deferred the expedition until reinforcements should arrive from France; and at the same time he did not feel entire confidence in the Indians, particularly since the time when he was cautioned on the subject by the Spaniards. It will not be foreign to my purpose to insert here something on this point, taken from the “History of Florida,” written and published by M. de Laudonnière.

“While” (says he) “the Indians were visiting me, always bringing some gift or other, as fishes, deer, turkeys, leopards, bear’s whelps, and other productions of the country, I, on my part, compensated them with hatchets, knives, glass beads, combs, and mirrors. Two Indians came one day to salute me in the name of their king, Marracon, who lived about forty miles southward from the fort. They informed me that there was living in the family of King Onachaquara a person called The Bearded; and that there was another with King Mathiaca, whose name they did not know, both foreigners. It occurred to me that these men might be Christians; and I therefore sent notice to all the chiefs in the vicinity, that if they had any Christians in their power, if they would bring them: in to me, I would reward them double. Under this inducement, such efforts were made that both, the persons referred to were brought to me at the fort. They were naked, and their hair hung down to their hams, in the Indian fashion. They were Spaniards by birth, but had become so accustomed to the manners of the natives that at first our ways seemed to them like those of foreigners. After talking with them I gave them some clothes, and directed their hair to be cut. This was done; but they kept it, putting it up in cotton cloth, saying that they would carry it back home with thorn as a testimony of the hardships which they had experienced in India. In the hair of one of them was found hidden a bit of gold, worth about twenty-five crowns, which he gave me. On my inquiring about the countries they had traveled through, and how they had made their way to this province, they replied that about fifteen years before, three ships, aboard one of which they were, had been cast away near Calos, on the rocks called The Martyrs; that King Calos had saved and kept for himself the greater part of the riches with, which these ships were laden; that such efforts were made that the greater part of the crew were saved, as were many women, of whom three or four were noble ladies, married, and who with their children were still living with this King Calos. On being asked who this king was, they said he was the handsomest and largest Indian of all that region, and an energetic and powerful ruler. They also reported that he possessed a great store of gold and silver, and that he kept it in a certain village in a pit not less than a man’s height in depth, and as large as a cask; and that, if I could make my way to that place with a hundred arquebusiers, they could put all that wealth into my hands besides what I might obtain from the richer of the natives. They said further, that, when the women met for the purpose of dancing, they wore, hanging at their girdles, flat plates of gold as large as quoits, and in such numbers that the weight fatigued and inconvenienced them in dancing; and that the men were similarly loaded. The greater part of all this wealth, they were of opinion, came from Spanish ships, of which numbers are wrecked in that strait; the rest from the trade between the king and the other chiefs in the neighborhood. That this king was held in great veneration by his subjects, whom he had made to believe that it was owing to his magical incantations that the earth afforded them the necessaries of life. The better to maintain this belief, he was accustomed to shut himself up along with two or three confidential persons in a certain building, where he performed these incantations; and any one inquisitive enough to try to see what was going on was at once killed by the king’s orders. They added, that every year at harvest time, this barbarous king sacrificed a man who had been set apart expressly for this purpose, and who was chosen from among the Spaniards wrecked in the strait. One of them also told how he had for a long time acted as a courier to this chief, and had often been sent by him to a certain chief named Oathkaqua, who lived four or five days’ journey from Calos, and had always been his faithful ally. Midway on his journey there is, in a great freshwater lake called Sarrope, an island about five miles across, abounding in many kinds of fruit, and especially in dates growing on palm-trees, in which there is a “great trade.” There is a still greater one in a certain root of which flour is made, of so good a quality that the most excellent bread is made of it, and furnished to all the country for fifteen miles round. Hence the inhabitants of this island gain great wealth from their neighbors, for they will not sell the root except at a high price. Moreover, they are reckoned the bravest of all that region, as they showed by their actions when, King Calos having allied himself to King Oathkaqua by taking the daughter of the latter in marriage, she was taken prisoner after the betrothal.

To return now to our gentlemen and soldiers who set out for New Spain after provisions. They went to Cuba, where they captured some vessels, in some cases with little difficulty, and laden with supplies of all kinds, such as cassava, olive-oil, and Spanish wine; and they took possession of these ships for their own purposes, leaving their own vessels. Not contented with this booty, they made descents upon several points in the island, carrying off enough plunder, as they reckoned, to come to two thousand crowns apiece. Afterwards they took, though not until after a fight; a swift vessel with great wealth on board, and with her the governor of a certain port in that island called La Havana. This official offered a great sum of money as a ransom for himself and his two children. The amount was agreed on, but there were required in addition four or six monkeys of the sort called saguins, which are very beautiful, and as many parrots, of which choice ones are found in that island; and the governor was to remain a prisoner on board the ship until the ransom should be paid. To all this he agreed, and suggested that it would be the quickest way to send one of his children to his wife with a letter explaining the terms. Our Frenchmen read this letter when he had written it, and, not seeing anything wrong in it, sent it to Havana, as suggested, in the boat of the ship. But, astute and cautious as they thought themselves, they had not heard a few words which the governor managed to whisper into his son’s ear; to wit, that his wife was not to do at all as was set forth in the letter, but was to send post-riders to every port in the island, to summon assistance. So effectively did the lady obey these orders that at daybreak next morning our ferocious Frenchmen found themselves beset by two large men-of-war, whose broadsides were ready to be opened upon them on either side, and another large vessel besides. Finding themselves thus trapped, as the entrance to the harbor where they lay was narrow, they were greatly cast down; but six and twenty of them threw themselves into a small fast-sailing vessel that was in the place, as she was less likely to be hit by the balls; and, cutting her cable, fought their way out through the enemy. All the rest, however, who remained on board the ship with the governor, were taken, and, except five or six who were killed in the affair, were carried off to the mainland, and thrown into prison. Part of them were afterwards sold as slaves, and taken to other places, even as far as to Spain and Portugal.

Among those who escaped, were the three chiefs of the conspiracy, Fourneaux, Stephen the Genoese, and La Croix. Trenchant the pilot, who had been forced to accompany them, was also in this party, with five or six sailors. These finding their craft without provisions, and that there was no way of getting any, agreed with each other to take the vessel back to Florida while the rest were asleep, which they did. The military men, when they awoke, were very indignant, for they were afraid of M. de Laudonnière: however, they concluded that it was best to put in at the mouth of the River of May for provisions, as they knew many Indians from whom they could get supplies; after which they could put to sea again, and try their fortune, unknown to the garrison at the fort, having accordingly reached the mouth of the river, they cast anchor, and began to search for provisions, when one of the Indians brought the news to M. de Laudonnière. On this, he was about to send them orders to bring the ship up opposite the fort, and appear before him; but Capt. La Caille begged him to proceed cautiously, as they might probably take to flight, instead of obeying, in which case the opportunity of making an example of them would be lost. ” Well,” said M. de Laudonnière, ” what do you advise, then?” — “I beg you,” answered La Caille, “to give me twenty-five arquebusiers, whom I will stow in one of the shallops, and cover with her sail, and get up to their vessel at daybreak. If they see only two or three of us, and a couple of hands managing the shallop, they will not object to our coming alongside; and, when we are close to them, my men shall spring up, and board them.” This plan was agreed to: the soldiers went on board; and when, next morning before daylight, the watch on board the other ship got sight of the boat, they called all hands. When, however, they recognized at some distance, on board the boat, only La Caille and a couple of men, they allowed them to come alongside without preparing to defend themselves. As soon as the boat was made fast to the vessel, however, our men sprang suddenly up, and boarded her. Surprised, they called out to fire on them, and ran to arms. But it was too late: they were quickly deprived of their weapons, and told that they were to be brought before the king’s lieutenant; which put them into consternation enough, as they felt that their lives were in the greatest danger. They were taken to the fort, and the three principal conspirators were regularly tried, condemned, and punished, while the rest being, however, discharged from the service, were pardoned; and there were no further seditions.

After this affair was settled, there was a great scarcity with us, because for various reasons the Indians, both those nearby and those farther off, all broke off their intercourse with us. One of these reasons was, that they obtained nothing from us in exchange for their provisions; another, that they suffered much violence from our men in their expeditions after supplies. Some were even senseless, not to say malignant, enough to burn their houses, with the notion that by so doing we should be more promptly supplied. But the difficulty daily increased, until we had to go three or four miles before we could meet a single Indian. Then there took place, moreover, a campaign against the powerful chief Outina, which I need not narrate, as an account of it is given in M. de Laudonnière’s work. In short, a detailed description of the condition of want to which we were reduced would be pitiful; but the plan of my work requires me to be very summary in my accounts.

After, however, some of us had actually perished of hunger, and all the rest were starved until our skin cleaved to our bones, M. de Laudonnière at last gave up hopes of receiving reinforcements from France, for which he had now been waiting eighteen months, and called a general council to deliberate on the means of returning to France. It was herein finally concluded to refit as well as possible the third of our ships, and to raise her sides with plank so as to enlarge her capacity; and, while the artificers were employed on this work, the soldiers were set to collect provisions along the coast.

While we were busily employed in this matter, however, a certain English commander named Hawkins, who was returning home from a long voyage, came up to our fort in his boat; and, on observing our miserable condition, offered us any assistance in his power, and proceeded at once to make his offers good, for he sold to M. de Laudonnière one of his ships at a very moderate price, together with some casks of flour which we baked into biscuits. He also gave us several casks of beans and peas, and accepted as part payment in advance some of our brass cannon, and then proceeded on his voyage.

We were rejoiced enough at thus getting possession of another vessel besides our own, which was being repaired, and of sufficient provisions for our return; and on consultation it was decided that before our departure the fort should be destroyed: in the first place, to prevent its being made, serviceable against the French, in case of their ever returning into those parts, by the Spaniards, who as we knew were desirous of establishing themselves there; and, secondly, to prevent Saturioua from occupying it. So we destroyed the works. After, however, we were quite ready for the voyage, and when we had been for three weeks only waiting for a fair wind to depart from the province, there unexpectedly arrived a fleet of seven ships, commanded by the famous Jean de Ribaud, well known for his great merits, and who was sent out to succeed M. de Laudonnière, and for the carrying-on of the king’s designs. This arrival, so wholly unexpected, filled us all with joy. M. de Ribaud landed with a number of his officers and many gentlemen and others. They all thanked God, while they were administering to our necessities, that they found us alive, for they had been informed that we had all perished; and so, after the long affliction which we had endured, God sent us happiness. All the new-comers individually were liberal in imparting food and whatever else they had brought, and tried in every way to be serviceable each to such friends or kinsmen or fellow-countrymen as he met with among us: so all the place was filled with happiness. But this joy was brief, as we quickly found.

M. de Ribaud desiring to land his treasure, provisions, and military supplies, had the mouth of the river sounded; but, finding too little water for his larger vessels, he ordered the three smaller ones only into the river. One of these, ” The Pearl” was commanded by his son Jacques de Ribaud, to whom Capt. Vallard of Dieppe acted as lieutenant; Capt. Maillard, also of Dieppe, commanded the second; and the captain of the third was a gentleman named Machonville. The four larger ships remained at anchor a mile from the shore, as the water was shallow there, and were unloaded by canoes and boats.

Seven or eight days after Ribaud’s arrival, while all the gentlemen, soldiers, and sailors, except a few men left in charge of the four larger ships, were on shore, and occupied about putting up houses, and rebuilding the fort, about four o’clock in the afternoon some soldiers who were walking on the seashore saw six ships steering towards our four which were at anchor. They instantly sent information to Ribaud; and upon his coming up, rather late, they told him that these six large ships had cast anchor near ours, which had at once cut their cables, and gone to sea under all sail; that the six had thereupon weighed anchor, and sailed in pursuit. Ribaud, indeed, and many others with him, were in season to see this chase with their own eyes. Our ships, however, being faster than the others, were quickly out of sight, and within a quarter of an hour the pursuers had also disappeared. This made us uneasy enough all the following night, during which Ribaud ordered all the small craft to be made ready, and stationed five or six hundred arquebusiers on the shore, in readiness to embark if needed. “Thus the night passed away, and the next day until about noon, when the largest of our four ships, “The Trinity,” came in sight, steering directly for us. Soon we saw the second, under Capt. Cossette, then the third, and a little afterwards the fourth; and they signaled us to come on board. But Ribaud fearing that the enemy might have taken the ships, and were trying to trap us would not risk his men, eager though they were to go aboard. As the wind was adverse, and the ships could not come in close, Capt. Cossette wrote a letter to Ribaud, which one of his sailors took, and, jumping into the sea at the imminent risk of his life, swam for shore. After swimming a long distance, he was seen from the land, and a boat put out, picked him up, and brought him to Ribaud. The letter was as follows:

“M. DE RIBAUD, —Yesterday at four, p.m., a Spanish fleet of eight ships hove in sight, six of which cast anchor near us. Seeing that they were Spaniards, we cut cables, and made sail; and they immediately made sail in chase, and pursued us all night, firing many guns at us. Finding, however, that they could not come up with us, they have made a landing five or six miles below, putting on shore; a great number of Negroes with spades and mattocks. On this state of facts, please to act as you shall see fit.”

On reading this letter, Ribaud at once called a council of his chief subordinates, including nearly thirty military officers, besides gentlemen, commissaries, and other civilians. The more prudent part of this assembly would have preferred to complete the erection and arming of the fort as soon as possible, while Laudonnière’s men, who knew the country, should be sent against the Spaniards; a plan which, God willing, would, they thought, quickly settle matters, since the locality was not within the Spanish jurisdiction, whose limits, indeed, were three or four hundred miles distant. Ribaud, however, after perceiving this plan to be generally acceptable, said, “Gentlemen, I have heard your views, and desire now to state my own. First, however, you should be informed that, a little before our leaving France, I received a letter from the admiral, at the end of which he had written with his own hand as follows: ‘M. de Ribaud, we have advices that the Spaniard means to attack you. Do not yield a particle to him, and you will do right.’ I must therefore declare plainly to you that it may result from your plan that the Spaniards will not await an assault from our brave men, but will at once escape aboard ship, by which we should lose our opportunity of destroying those who are seeking to destroy us. The better plan seems to me to be, to put all our soldiers on board our four ships now at anchor, and to seize at once upon their ships, while anchored where they have landed. When those are taken they will have no refuge except the works which their slaves have been throwing up; and we can then attack them by land to much better advantage.”

M. de Laudonnière, who was by this time familiar with the climate of the country, now suggested that the weather should be carefully taken into account before putting the men on board ship again; as at that time of year a species of whirlwinds or typhoons, which sailors call “houragans,” from time to time come on suddenly, and inflict terrible damage on the coast. For this reason he favored the former of the proposed plans; the rest, for the same and other reasons, have already been described as of the like mind. Ribaud alone, however, condemning all their reasons, persisted in his own determination, which was no doubt the will of God, who chose this means of punishing his own children, and destroying the wicked. Not satisfied with his own force, M. de Ribaud asked for Laudonnière’s captains and his ensign, whom the latter could not well refuse to send with him; and all Laudonnière’s men, when they saw their standard-bearer going, insisted on going with him. I myself, seeing them all going, went on board with the rest, though lame in one leg, and not yet recovered from a wound I had received in the campaign against Outina.

All the troops being now on board, a fair wind for an hour or two was all that was needed to bring us up with the enemy; but just as the anchors were about to be weighed the wind changed, and blew directly against us, exactly from the point where the enemy were, for two whole days and nights, while we waited for it to become fair. On the third day, as signs of a change appeared, Ribaud ordered all the officers to inspect their men; and M. d’Ottigny finding in his examination Laudonnière’s force, that I was not yet quite cured, had me put into a boat along with another soldier, a tailor by trade, who was at work on some clothes for him against the proposed return to France, and sent us, against our wills, back to the fort. But just as they had weighed anchor, and set sail, there came up all at once so terrible a tempest that the ships had to put out to sea as quickly as possible for their own safety; and, the storm continuing, they were driven to the northward (southward?) some fifty miles from the fort, where they were all wrecked on some rocks, and destroyed. All the ships’ companies were, however, saved except Capt. La Grange, a gentleman of the house of the Admiral de Châtillon, a man of much experience and many excellencies, who was drowned. The Spanish ships were also wrecked and destroyed in the same gale.

As the storm continued, the Spaniards, who were informed of the embarkation of the French forces, suspected, what was not so very far from the truth, that the troops had been cast away and destroyed in it, and fancied that they could easily take our fort. Although the rains, continued as constant and heavy as if the world was to be again overwhelmed with a flood, they set out, and marched all night towards us. On our part, those few who were able to bear arms were that same night on guard; for, out of about a hundred and fifty persons remaining in the fort, there were scarcely twenty in a serviceable condition, since Ribaud, as before mentioned, had carried off with him all the able soldiers except fourteen or fifteen who were sick or mutilated, or wounded in the campaign against Outina. All the rest were either servants or mechanics who had never even heard a gun fired, or king’s commissaries better able to handle a pen than a sword; and, besides, there were some women, whose husbands, most of them, had gone on board the ships. M. de Laudonnière himself was sick in bed.

When the day broke, nobody being seen about the fort, M. de la Vigne, who was the officer of the guard, pitying the drenched and exhausted condition of the men, who were worn out with long watching, permitted them to take a little rest; but they had scarcely had time to go to their quarters, and lay aside their arms, when the Spaniards, guided by a Frenchman named François Jean, who had seduced some of his messmates along with him, attacked the fort at the double quick in three places at once, penetrated the works without resistance, and, getting possession of the place of arms, drew up their force there. Then parties searched the soldiers’ quarters, killing all whom they found, so that awful outcries and groans arose from those who were being slaughtered. For my own part, whenever I call to mind the great wonder that God, to whom truly nothing is impossible, brought to pass in my case, I cannot be enough astonished at it, and am, as it were, stunned with the recollection. On coming in from my watch, I laid down my arquebuse; and, all wet through as I was, I threw myself into a hammock which I had slung up after the Brazilian fashion, hoping to get a little sleep. But on hearing the outcries, the noise of weapons, and the sound of blows, I jumped up again, and was going out of the house to see what was the matter, when I met in the very doorway two Spaniards with their swords drawn, who passed on into the house without accosting me, although I brushed against them. When, however, I saw that nothing was visible except slaughter, and that the place of arms itself was held by the Spaniards, I turned back at once, and made for one of the embrasures, where I knew I could get out. At the very place I found five or six of my fellow-soldiers lying dead, among whom were two that I recognized, La Gaule and Jean du Den. I leaped down into the ditch, crossed it, and went on alone for some distance over rising ground into a piece of woods, until, having reached higher part of the hill, it was as if God gave me back my consciousness; for it is certain that the things that had happened since my leaving the house were as though I had been out of my wits. I now prayed to God for his guidance in my actions, in this so extreme danger; and, at a suggestion from his Spirit, went forward into the woods, whose paths, by frequent use of them, I well knew. I had gone but a little way when, to my great joy, I came upon four other Frenchmen; and, after condoling with each other, we consulted on what to do next. Part of us advised to stay where we were until next day, when perhaps the fury of the Spaniards would be appeased; and then to return, and surrender ourselves to them, rather than risk being devoured by wild beasts where we were, or perishing by hunger of which we had already endured so much. Some of the rest, not liking these suggestions, thought it a better plan to make our way to some distant Indian settlement, where we might live until God should open some way for us. But I said, “Brothers, I like neither of these suggestions. If you will be guided by me, we will make for the seashore through the woods, and try if we cannot discover something of the two small vessels which Ribaud sent into the river to be used in disembarking the provisions he brought from France.” But,this appearing to them perfectly impracticable, they set off to find the Indians, leaving me alone. But God, taking pity on my distress, sent me another companion, being Grandchemin, that very soldier whom M. d’Ottigny sent back with me to the fort to work on some clothes for him. I suggested to him the same as to the others, that is, to endeavor to find the two small craft at the seashore. He thought well of this, and we were all that day on the road before we got through the woods. Before we could reach the shore, how-ever, we had extensive swamps to pass, all thickly grown with large reeds, very hard to get through. With all this toil we were pretty well exhausted when night fell, and a steady rain began also to come down upon us. The tide likewise rose in the swamp until the water there among the reeds was over our waists; and we spent the whole night in working our way onward under these difficulties. When the daylight came, and we could see nothing in the direction of the sea, the soldier, losing his patience, said it would be better to surrender ourselves to the enemy, and that we might as well return to them; that, when they found that we were artificers, they would spare our lives; and, even if they should not, was it not better to let them kill us than to remain any longer in such a miserable condition? I sought to dissuade him, but in vain; and, as I saw that he was about to leave me, I finally promised to go back with him to the Spaniards. We therefore made our way back through the woods, and were even in sight of the fort, when I heard the uproar and rejoicing which the Spaniards were making, and was deeply moved by it, and said to the soldier, “Friend and companion, I pray you, let us not go thither: let us stay away yet a little while; God will open some way of safety to us, for he has many of which we know nothing, and will save us out of all these dangers.” But he embraced me, saying, “I will go: so farewell.” In order to see what should happen to him, I got up a height nearby, and watched. As he came down from the high ground, the Spaniards saw him, and sent out a party. As they came up to him, he fell on his knees to beg for his life. They, however, in a fury cut him to pieces, and carried off the dismembered fragments of his body on the points of their spears and pikes. I hid myself again in the woods, where, having gone about a mile, I came upon a Frenchman of Rotten, La Crete by name, a Belgian called Elie des Planques, and M. de Laudonnière’s maid-servant, who had been wounded in the breast. We made our way towards the open meadows along the seashore; but, before getting through the woods, we found M. de Laudonnière himself, and another man named Bartholomew, who had received a deep sword-cut in the neck; and after a time we picked up others, until there were fourteen or fifteen of us in all. As, however, a Carpenter called Le Chaleux, who was one of us, has given a brief account of this part of our calamities, I will say nothing more except that we traveled in water more than waist-deep for two days and two nights through swamps and reeds; M. de Laudonnière, who was a skillful swimmer, and the young man from Rouen, swimming three large rivers on the way, before we could get sight of the two vessels. On the third day, by the blessing of God, and with the help of the sailors, we got safe on board.

I have already mentioned, that, as Ribaud found that there was not water enough at the mouth of the river to admit his four largest vessels, he had sent in his three smaller ones, which he purposed to use in discharging the others; his son Jacques de Ribaud being in command of the largest of the three. He had taken his vessel up to the fort, and lay there at anchor while the Spaniards were perpetrating their butchery; nor, although he had cannon, did he once fire upon them. All that day the wind was contrary, and prevented him from getting the ship out of the river. The Spaniards in the meantime offered him good terms and amnesty if he would surrender, to which he made no reply. When they saw that he was trying persistently to get his ship out to sea, they took a small boat which was used at the fort, and sent her on board of him with a trumpeter, and that same traitor, François Jean, who had guided the Spaniards into the fort, to request a parley to arrange terms of agreement. And, although this traitor was reckless enough to even venture himself aboard of the ship of Jacques de Ribaud, the latter was so imbecile and timid as not to venture to detain him, but let him go safe back again, although he had on board, besides his crew, more than sixty soldiers. But, on the other hand, neither did the Spaniards, although they had abundance of small boats, dare to make any attacks upon him.

On the next day, however, Jacques got his ship to the mouth of the river, where he found the other two smaller vessels nearly emptied of men; for the greater and better part of them had gone with Jean de Ribaud. Laudonnière therefore decided to fit out and man one of the two with the armament and crews of both; and then advised with Jacques what they should do, and whether they ought not to search for his father; to which the latter made answer that he wanted to go back to France, which was in the end resolved upon. First, however, as there was no provision except biscuit in the smaller vessel, and she was without water, Laudonnière had some empty casks filled with water, and Jacques did the like. In this, and in obtaining some other necessary supplies, two days were consumed, during all which time the ships were kept close side by side, for fear the Spaniards might attack us, as their boats reconnoitered us from time to time, not, however, venturing within gunshot distance. Certainly, as we knew what actions they had perpetrated upon our friends, we were prepared to make a desperate defense.

Before sailing, Laudonnière asked Jacques de Ribaud to accommodate him with one of his four pilots, as he had no skillful navigator on board, but was refused. He then further observed that it would be well to sink our vessels left at the mouth of the river, lest the Spaniards should get possession of them, and use them to prevent Jean de Ribaud from entering the river, should he return and wish to do so (for we were ignorant of his shipwreck); but Jacques would consent to nothing. Laudonnière, finding him so obstinate, sent his own ship-carpenter, who scuttled and sunk the ships in question; namely, one which we had brought from France, one which we had bought of the English commander Hawkins, and one the smallest of M. de Ribaud’s fleet; and, this done, we set sail from Florida, ill manned and ill provisioned. But God, however, gave us so fortunate a voyage, although attended with a good deal of suffering, that we made the land in that arm of the sea bordering on England which is called St. George’s Channel.

This is what I have thought it proper to relate of the things which I witnessed on this voyage; from which it appears that victory is not of man, but of God, who does all things righteously according to his own will. For, according to all human judgment, fifty of the worst of Ribaud’s soldiers could have destroyed all the Spanish force, of whom many were beggars and the dregs of the people; while Ribaud had more than eight hundred brave veteran arquebusiers, with gilded armor. But, when such things are God’s pleasure, it is for us to say, Blessed be the name of God everlasting!