Like the account of Mary Godfrey almost two decades later, Eunice Barber’s 1818 account of a Creek-Seminole attack on white settlers was produced as a “print commodity created for consumers of popular narratives” (Williams 300). But unlike the Godfrey account, the voice is consistently presented as that of Barber’s, and the text more clearly serves as a subsequent justification and explanation of General Andrew Jackson’s cross-border incursions perpetrated in 1816 to attack communities of Indians and escaped blacks he contended harbored American property as well as British insurgents.

Like the account of Mary Godfrey almost two decades later, Eunice Barber’s 1818 account of a Creek-Seminole attack on white settlers was produced as a “print commodity created for consumers of popular narratives” (Williams 300). But unlike the Godfrey account, the voice is consistently presented as that of Barber’s, and the text more clearly serves as a subsequent justification and explanation of General Andrew Jackson’s cross-border incursions perpetrated in 1816 to attack communities of Indians and escaped blacks he contended harbored American property as well as British insurgents.

The experience of Eunice Barber, who may be a representation of the peaceful settler captive, mirrors other fictional accounts in important ways, and the insight her incredible fortune leads her to provide allows the reader to experience the sensation of special perspective on the war preparations of the Creeks and Seminoles. The country at this time was thirsty for information about these battles of expansion, and supporters of Jackson, and proponents of continental conquest, gladly fed the fire of nationalism with the recurrent specters of the scalping knife and tomahawk. While attacks on white settlements placed conspicuously in disputed territory doubtlessly occurred, and were also encouraged by British agents for a time, the bloodthirsty “savages,” of these accounts commit specific offenses, such as women and children participating in torture and acts of war, that could further justify the genocidal spirit Jacksonian expansionism required.

Edited by Keith Lewis Simmons, University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Further Reading

Williams, Daniel E. and Christina R. Brown (eds.). Liberty‘s Captives: Narratives of Confinement in the Print Culture of the Early Republic. Athens: U Georgia P, 2006.

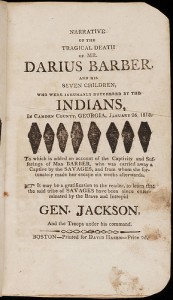

Barber, Eunice. NARRATIVE of the TRAGICAL DEATH of Mr. DARIUS BARBER AND HIS SEVEN CHILDREN, WHO WERE INHUMANLY BUTCHERED BY THE INDIANS, IN CAMDEN COUNTY, GEORGIA, JANUARY 26TH, 1818. Boston: David Hazen, 1818.

To which is added and account of the Captivity and Sufferings of Mrs. BARBER, who was carried away a Captive by the SAVAGES, and from whom she fortunately made her escape six weeks afterwards.

It may be a gratification to the reader, to learn that the said tribe of SAVAGES have been since exterminated by the Brave and Intrepid GEN. JACKSON, And the Troops under his command.

In the evening of the 26th of January last, my husband (Darius Barber, who resided near the line, in Camden county) having imprudently retired to bed, without taking the precaution to secure the doors of the house as usual, about eleven at night we were awakened by the horrid yell of savages who to the number of thirty or forty, to our inexpressible horror, we saw standing over us with uplifted tomahawks!–Mr. Barber jumped instantly out of bed and attempted to reach an extreme corner of the room, where his fire arms were deposited, but a dozen tomahawks aimed at him at once, brought him lifeless to the floor—they then seized me by my hair and drew me from the bed, brandishing their knives before me with frightening grimaces and a terrible shout, as if about to dispatch me—others tomahawked and scalped my poor children, as they lay in their bed unconscious of harm, in a room adjoining—a hired man who lodged in the chamber, and who attempted to make his escape by jumping out of the window, suffered a similar fate. Having completed their bloody work thus far, they led me nearly naked to a spot a little distance from the house, from which they bid me not to move on peril of my life. The Savage monsters now proceeded to pillage the house of every thing valuable, and in their researches, they discovered my only surviving child, my daughter of ten years of age, who during the awful butchery of my other children, had unperceived crept from her bed and secreted herself behind a desk—observing herself discovered, she broke through the savages and succeeded in reaching the door, when espying me at a little distance, she ran up to me and with the most plaintive accents, begged that I would intercede for her, and implore the savages to spare her life!—she was closely pursued by one of the blood thirsty monsters, of whom I begged that he would spare the life of my only surviving child! but my entreaties and lementations were of no avail, my poor child was tomahawked in my arms!!—heaven only knows what were my feelings at this moment.

The Savages loaded themselves with the most valuable contents of the house, and departed, compelling me to accompany them with a heavy load. They bent their course towards their own settlement, which they reached after a tedious travel of six days, over steep mountains and through almost impenetrable thicket and swamps. At the entrance of their village, they daubed my face and body with black and red paint, and dressed my head with feathers, in imitation of their own leathers, in imitation of their own!—as soon as they had completed thus decorating my person, according to their Indian mode, they all set up a terrible yell, which was probably to announce their approach to their brethren in the village, as they were very soon met by two or three hundred of them to whom they, with an air of triumph, exhibited the bleeding scalps of my poor children which was viewed by the unfeeling wretches with much apparent satisfaction. While the older ones were employed in examining the articles of plunder which their brethren had brought with them! Their children formed a circle around me, and were permitted to insult and torment me in whatever manner they pleased—sometimes presenting to my view the scalps of my poor husband and children, and then would mimic their dying groans!

The Savages having satisfied their curiosity, they conducted me to one of their wigwams, and left me in charge of an old Indian and his squaw—Here I found two more white captives, two lads of the age of 11 and 15—the poor youths informed me that they had been in captivity nearly four weeks; that they were from Camden county, that their house was attacked about midnight by the savages, who killed both their parents and older brother.

While I remained a prisoner with the Indians I was witness of many of their brutal acts, and endured hardships, which it would have been impossible for many females to sustain! Indeed, human imagination can hardly figure to itself a more deplorable situation. I became the property of an old, Savage, and my place of abode was a filthy wigwam unfit for shelter for dumb beasts.—My food was the offal of such wild animals as were destroyed in the chase, and my bedding was no other than a few hemlock branches—with cloathing scarcely sufficient to cover me, and my arms, face and legs gashed with wounds and swollen with bruizes, to have quit the world at this moment, would scarcely have cost a single pang—my thought was ultimately filled on a happier state of existence, beyond the tortures I endured—the bitterness of death, even of that death which is accompanied with the keenest agonies, was, in a manner, past. Nature, with a feeble struggle, seemed inclined to quit its last hold on sublunary things.

My savage master in one of his hunting excursions (unwilling to leave me behind) compelled me to accompany him.—During his rambles, I was frequently on the point of perishing with hunger, to allay which, a little Bear’s meat was given me which I sucked through my teeth. My master having one morning wounded a Buck in such a manner as he supposed it could not escape, left it in my charge but the animal soon recovering his strength and from my very weak state being unable to secure it, it escaped from me. When my master and his two savage companions returned they not only manifested their malevolence for the disappointment, by horrid grimaces and angry gestures, but declared they would roast me! –with this apparent intention they led me to a dark forest, stripped me naked and bound me to a tree, and piled dry brush, with other fuel at a small distance in a small circle round me they accompanied their labour as if for my funeral dirge, with screams and sounds inimitable but by savage voices. I now concluded that my final hour was inevitably come—I summoned all my resolution and composed my mind as far as the circumstance could admit, to bid an eternal farewell to a troublesome world! but at the very moment that I expected that fire would be communicated to the fatal pile, my master approached and unbound me, and giving me a severe blow with the handle of his tomahawk, led me out of the thicket. I was now ordered to wrap an Indian blanket around me, and was loaded with as much of their game as could be piled upon me, strongly pinioned, and my wrists tied as close together as they could be pulled with a cord. After being compelled to march through no pleasant path, in this painful manner, for many a tedious mile, the party (who as well as myself were excessively fatigued) halted to breathe. My hands were now immoderately swelled from the tightness of the ligature, and the pain had become intolerable—my feet were so much scratched that the blood dropped fast from them—exhausted with bearing a burden above my strength, and frantic with torments exquisite beyond endurance, I implored of my savage master to unbind me or to dispatch me at once and take my scalp!

Early one morning we fell in with nine more Indians (warriors) of the same tribe, who were in pursuit of a company of their Indian enemies, who a few days previous had surprised and plundered a number of their wigwams. It was soon agreed by both parties that we should join them in the pursuit; that I might be enabled to keep pace with them, my hands were unbound, and a pair of moccasins were allowed me, and I was permitted to march without any pack, or receiving any insult.

After a rapid march of three days over steep and ragged mountains, and through thick and pathless swamps, we came up with the objects of our pursuit—they were just the number of my conductors, and well armed; a warm contest was therefore to be expected. A tomahawk was put into my hands by my master, who ordered me to dispatch such of the wounded of the enemy as during the action I should discover attempting to make their escape (rather would I have sunk it into the head of this, the murderer of my dear husband and children.)

In a few moments a bloody conflict commenced, accompanied with frightful whoops, and horrid yells both parties were armed with muskets, knives and tomahawks, and both seemed determined on death or conquest. The action, though principally fought between man and man, soon grew intensely warm—it would be as difficult as useless to describe their irregular and ferocious mode of fighting; some times they fought aggregately in open view, and sometimes individually under cover; taking aim from behind the bodies of trees, and acting in a manner independent of each other.

Among the rest my master received a severe wound and fell, but raising himself upon his hands and knees, he was just enabled to creep unperceived by the enemy, into a thicket—not until this moment did it occur to me for what purpose the hatchet had been put into my hands it was to dispatch a wounded enemy; and could I look upon greater, than be who in the most barbarous manner deprived me of my innocent husband and children; for a moment I surveyed the instrument yet crimsoned with the blood of the unhappy victims, and hastened to retaliate upon the wretch who was deaf to their entreaties for mercy! As I approached him as if sensible of my determination, he raised himself upon his knees in a supplicating attitude; but as I well knew that he who would not shew mercy to the defenceless, could not expect to receive it from others, I instantly aimed a blow at his head, and continued to repeat them until I was sure that he was quite dead—this I accomplished without being discovered by any of his brethren, who were too warmly engaged with their enemies to notice which of their party were slain.

After a bloody conflict of near two hours continuance, victory decided in favour of my captors, who having destroyed seven and wounded two of the enemy, put the others to flight. After the engagement, in numbering their own living, it was discovered that four had been slain and three wounded—my master was found in the thicket in the situation in which I left him, nor did they dream of his having fallen by any other hand than that of his Indian enemies. Their own killed they buried after their Indian mode on the spot, and scalped those of their enemies and suffered their bodies to lie above ground.

Having constructed an Indian litter, for the conveyance of their wounded, and of their prisoners, they set out on their return to their village, which they reached four days after—at the entrance, the prisoners were decorated with fine feathers, vermillion &c. as usual, and ordered to sing a death song—in a very few moments they were met by many hundreds of villagers, men, women, and children, who caused by the way of savage triumph, caused the woods to resound with the whoops and yells-but, as soon as they were made acquainted with the number of their friends slain, their exulting airs and vociferations were changed & the most dreadful howlings and bitter lementations now rent the air; nor did they fail to reek their vengeance on their unfortunate prisoners, whom they pelted with clubs and stones, so that they were hardly enabled to walk.

The conquering savages having lost three of their number killed, the fate of the two wounded prisoners was very soon determined; they were sentenced (in retaliation for the deaths of their friends) to be tortured after their Indian mode. The dreadful sentence was no sooner passed then the whole village set up the death-cry, preparatory to their rioting in the most diabolical cruelty.—The unhappy captives were first stripped, and bound to three posts that had been erected for the purpose, their bodies were next stuck from their necks to their waists with a small pitch pine splinters, the blood gushing out at every puncture; all this the unfortunate victims sustained without a complaint!—in this situation they were compelled to remain for more than one, hour, while the men, women and children of the whole village, were permitted and encouraged to torture them, in whatever manner they pleased each striving to exceed the other in cruelty—the small splinters were then set on fire, which very soon placed the miserable sufferers beyond the reach of savage torture!

What is very extraordinary, not a groan, nor a sigh, nor a distortion of counternance escaped the victims during their torments—there indeed seemed during the whole distressing scene a contest between them, and their tormentors, which should out do the other, they in inflicting the most horrid pains, or the prisoners in enduring them!

During my captivity I almost daily saw hordes of savages returning from their expeditions against the white settlements, loaded with human scalps, and draging into captivity more or less of their defenceless inhabitants.—Among these unfeeling monsters I found too a number of wretched beings who had been much longer in captivity than myself—among these I became acquainted with one of my own sex, a Mrs. White, who had been nearly two years a prisoner among them, and whose history I am certain could not be read without emotion , if it could be written in the same affecting manner, in which she related it to me. She was still young and handsome as the troubles which she had experienced had taken somewhat form the original redundancy of her bloom, and added a softening paleness to her cheeks, rendered her appearance the more engaging. Her face, that seemed to have been formed for the assemblage of dimples and smiles, was clouded with care. The natural sweetness was not, however, soured by despondency and petulance; but chastened by the humility and resignation. This unhappy woman looked as if she had known the day of prosperity, when serenity and gladness of soul were the inmates of her bosom. That day was past, and the once lively features, now assumed a tender melancholy, which witnessed her irreparable loss. She wedded not the customary weeds of mourning, or the fallacious pageantry of woe to prove her widowed state. Everything conspired to confirm and to make her story interesting.—Her father was killed by the Indians at the time of St. Clair’s defeat—her mother and two of her sisters were taken captives by the savages soon after, and was never after heard of—her husband and three of her children were inhumanly butchered by the Indians on the night of the 10th of May, 1815, and herself and the remainder of her children (five in number) led away into captivity! She was for some months held a prisoner by the clan of Savages who first took her, and during their rambles was often subjected to the hardships seemingly intolerable to one of so delicate a frame. The Indians at length separated, and carried off four of her youngest children into different tribes!—of no avail where the entreaties of their tender mother—a mother desolated by the loss of children, who were torn from her fond embraces, and removed many hundred miles from each other into the utmost recesses of the wild wilderness!

With them (could they have been kept together) she would most willingly have wandered to the extremities of the world, and accepted as a desirable portion the cruel lot of the slavery for life. But, she was precluded from the sweet hope of ever beholding them again. The insufferable pangs of parting, and the idea of eternal separation planted the sorrows of despair deep in her soul. This unfortunate woman begged of me, if I should ever be so fortunate first to gain my liberty and should be again restored to the arms of my Christian friends, that I would beseech them to take measures to liberate her and her unfortunate children from cruel bondage—this I promised her I would do, nor have I failed to keep my promise—soon after my fortunate escape, I represented to the proper Authority the situation of this wretched woman, who, with the aid of government, are about to adopt measure to resque the fair prisoner from the hands of the barbarians.

As I observed, while I was held prisoner by the savages, parties from 10 to 20 were almost constantly employed in expeditions against the Christian settlements—their return to the village was always announced by whoops and yells, when the whole inhabitants of the village who had power to use their legs, hastened to meet them, and if their expedition had been a successful one, on their meeting, they united their voices with those of the captors, in their ejaculations of triumph.—But if they had experienced a reverse of fortune, it was announced by dismal howls, and great lamentation by those whose friends had been slain.—If a single prisoner was brought in, those who had lost a friend in the expedition, had the power to determine his fate, either to adopt him in the place of the deceased, or to doom him to savage torture—if they were disposed to save his life he was unbound, taken by the hands, led to the cabin of the person into whose family he was to be adopted, and received with all imaginable marks of kindness. He was then treated as a friend and a brother, and they appeared soon to love him with the same tenderness as if he stood in the place of their deceased friend. In short, he had no other marks of captivity, but his not being suffered to return to his own nation, for should he have attempted this, he would have been punished with death,–But, if the sentence be death, how different their conduct! these people, who behave with such disinterested affection to each other, with such tenderness to those whom they adopt, here show that they are truly savages; the dreadful sentence is no sooner passed, than the whole village set up the death-cry; and, as there was no medium between the most generous friendship and the most inhuman cruelty; for the execution of him whom they had just before decided upon admitting to their tribe, is no longer deferred, than whilst they can make the necessary preparations for rioting in the most diabolical cruelty! preparations to destroy life by torture!—

Among those who held me in captivity there appeared to be many of the Creek Nation, who harboured great inveteracy against the American troops for depriving them of their lands, particularly their Commander in Chief, Gen. JACKSON, whom (as all the neighboring tribes had engaged to join them in the War against the whites) they vainly hoped soon to have in their power—so confident did they appear to be of this, that they had really held meetings of consultation to devise means how, and in what way they should inflict the most excruciating torture upon him—his heart, it was pretty generally agreed should be divided into as many detached pieces as there should be tribes engaged in the war, and a piece presented each, while his scalp, was to be property of Francis, their distinguished leader! thus had they agreed to dispose of their much dreaded enemy, General JACKSON!—little thinking then, that this distinguished Commander was so soon to march fearlessly into the very heart of their village, lay their wigwams in ashes, and compel them to sue for peace, which he has actually since done!

A few weeks after I was taken prisoner, the Indians held a Council of War, at which my Indian master permitted me to be present—the Council was composed of the chiefs and heads of families, whose capacity had raised them to the same degree of consideration.—When they had assembled, the Chief Sachem first arose and taking up a tomahawk which lay by his side, with a stern voice enquired “Who among you will go and fight the white men?” “Who among you will bring captives from their settlements to replace our deceased friends, that our wrongs may be revenged and our name and our honour maintained, as long as the rivers flow, the grass grows, or the sun and moon shall endure? upon which one of the principal warriors arose, and harangued the whole assembly, and afterwards addressed himself to the young men, enquiring who among them would go along with him, and fight the white people; who thereupon all generally arose one after another, and fell in behind him, while he walked around the circle.

Their feast, which always attends their Council of War, now began on this occasion—there was a whole deer roasted, from which each, as they consented to go to war, cut off a piece, and eating it, said, “Thus will I devour our white enemies!” This ceremony being performed, the war-dance began, each singing the war-song, which related to their intended expedition, and conquest, and to their own skill and dexterity in fighting, and the manner in which they would vanquish their enemies! Their expressions were strong and pathetic, attended with a tone that could not fail to inspire terror in the timid female.

The next week the warriors assembled to set out upon their intended expedition—their military appearance was odd and terrible—they cut off all their hair, except a spot on the crown of their head, and plucked out their eye-brows the lock which they left upon their heads, they divided into several parcels, each of which they stiffened and intermixed with beads and feathers of various shapes and colors, twisting and connecting the whole together. They painted themselves with red pigment, down to the eye-brows, which they sprinkled over with white down. They slit the gristle of their ears almost quite round, and hung them with ornaments that generally had the figure of some bird or beast, drawn upon them—their noses (which were bored) were likewise hung with beads, and their faces painted with various colors—on their breasts they wore a gorget or medal of brass or copper, and by a string around their necks was suspended that horrid weapon the scalping knife!

Thus equipped, they proceeded for the white settlements, singing their war-song until they lost sight of the village—they were attended by many of their squaws, who assisted them in carrying their baggage—they were to the number of nearly one hundred in the whole; but, it gave me inexpressible satisfaction to see but once half this number return 10 or 12 days afterward—the rest having been slain by the whites. While I inwardly exulted at their bad success, they seemed anxious to discover some object on whom they could retaliate, nor was I with out my fears that I should myself be selected as a victim on whom they might reek their vengeance—they did not however appear disposed to exercise more cruelty towards me than what they had previously done.

During the six weeks of my captivity, I am confident there were more than 50 prisoners (men, women, and children) brought in by the Savages, beside many horses and other property to a very great amount. The particulars of many of the instances of barbarity exercised upon the prisoners of different ages, and sexes, and to which I was eyewitness, are of too shocking a nature to be presented to the public—it is sufficient here to observe that the scalping knife and tomahawk, were the mildest instruments of death—that in many cases torture by fire, and other execrable means were used.

I remained nearly five weeks in charge of my Indian master, and when being sent very late one evening for some water, I conceived it the most favourable opportunity that I should probably have to escape.—I proceeded without delay to a very thick swamp, where I concealed myself until it was quite dark & then proceeded in search of a tract, that might lead me to some white settlement, without the risk of being lost, and perishing with hunger. Taking a path leading in the direction of the settlement from which I had been taken, as I judged, about the break of day, three or four Indians passed within a few rods of me, without perceiving me!—these I concluded were probably my pursuers, and excited emotions of gratitude and thankfulness to divine providence for my deliverance. Being destitute of every kind of provision, and having no kind of instrument or weapon by which I might procure it, and being nearly as destitute of cloathing, and entirely unacquainted with the method of traveling through a wild wilderness, excited painful sensations-but certain death, either by hunger or wild beast, seemed preferable rather than to be in the power of beings whose awful barbarity was still fresh in my mind. I addressed heaven for protection, & proceeded onward, sometimes penetrating thick and dismal swamps, at other times crossing high and craggy mountains, unmarked with the footsteps of any human being. After travelling four days, my course was obstructed by a river—after proceeding up the same, for several days. I came to a prodigious waterfall, and numerous high craggy cliffs along the water edge; that way seemed impassible, the mountain steep and difficult—however, I concluded that the latter way was the best. I therefore ascended for some time, but coming to a range of inaccessible rocks, I turned my course, towards the foot of the mountain and river side; after getting into a deep gully, and passing over several high steep rocks, I reached the river side, where to my inexpressible affliction, I found that a perpendicular rock, or rather one that hung over, of 15 or 20 feet high, formed the bank. Here a solemn pause took place; I essayed to return, but the height of the steep rocks I had descended over, prevented me. I then returned to the edge of the precipice, and viewed the bottom of it, as the certain spot to end all my troubles, or remain on the top to pine away with hunger, or be devoured by wild beasts. After serious meditation, and devout exercises, I determined on leaping from the height and accordingly jumped off. Although the place I had to alight on, was covered with uneven rocks, not a bone was broken; but, being exceedingly stunned with the fall, I remained unable to proceed for some space of time.

As five days had passed since I had received any other nourishment, but what the roots and bark of trees afforded hunger, fatigue and grief, reduced me to a mere skeleton—as I was apprehensive that I should very soon fall a victim to one or the other, at times, I was ready to reproach myself for having attempted to effect my escape. After crossing the river, I travelled a south-east course for two days, but with as little prospect of reaching a friendly settlement—my spirits as well as strength began to fail me; I conceived myself the most wretched and forlorn of human beings! altho’ until now I had been enabled to support nature by chewing and swallowing the juice of young cane sticks, the roots and bark of sassafrass, &c. my hunger was too great to be any longer endured. About noon of the seventh day from my escape, as I was seated on the summit of a rock, upon a high hill, meditating on my wretched condition, the pleasing sound of the woodman’s ax, (which proceeded from the valley below) met my ear! As I concluded this must be some friendly inhabitant employed in falling timber, I hastened to the spot, and to my inexpressible joy, found myself not mistaken—it was the Christian friend by whom I was yesterday conducted to this village.”

Thus, after remaining six weeks a prisoner among the cruel Savages, in which time I experienced every hardship and cruelty which it was in the power of the inhuman monsters to inflict—by the interference of Divine Providence in my behalf, I was at length rescued from their hands—although bereaved of my kind husband and tender children, who all in one fatal night fell victims to savage barbarity, yet, I feel that I ought not to “charge the Almighty foolishly” I would rather acknowledge it right and just, that I have been saved.—God chastiseth him whom he loveth—it was his will and pleasure that I should be preserved amid the perils and dangers with which I have been surrounded—through his kind interposition was I saved from the tomahawk and scalping knife in the most exasperated moments of the Savages—He was my friend and protector, while a sojourner in the wilderness, and saved me from the ravenous jaws of the wild beasts—miserable must I have been had I been cut off in the midst of my transgressions!—Thanks to Him, who knows the impurity of every heart, that I have been spared yet a little while longer to repent of my manifold sins—may I improve the remaining precious moments of my life in such a way as will insure me permanent and uninterrupted happiness in the world to come.

EUNICE BARBER