Alonso Gregorio de Escobedo, a Franciscan hailing from Andalucía, arrived in St. Augustine on October 7, 1587. Little is known about his life, except for what he included in his epic poem “La Florida.” Penned sometime between 1598 and 1615, this massive composite work was modeled after the metrically elegant style of the octava real, the preferred poetic structure in Spanish letters at his time. Written as a poem, rather than a historical document, “La Florida” is read today for its anthropologically significant information, such as the description of Indian fishing practices found in Canto 27. The complete manuscript, housed in the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, was published as a 1993 dissertation by Alexandra Elizabeth Sununu, and has appeared piecemeal in English, but has never been fully or adequately translated.

In its entirety, the poem covers multiple themes including but not limited to the life of a model Christian named San Diego de Alcala, the Guale Rebellion, the experiences of the first Spaniards to travel to the Western Hemisphere, and pláticas (or sermons) with Biblical topics. The following selections include Cantos 27 and 28. In Canto 27, Escobedo judges the natives according to the customs of which he has knowledge, and he details their fishing practices. In Canto 28, he describes how the Indian leaders maintain the loyalty of their people, how the Indians play their ball game, how they bet on foot races, and how they bury their dead.

Edited by Mikaela Perron, University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Further Reading

Covington, James W. (ed.). Pirates, Indians and Spaniards: Father Escobedo’s La Florida. St. Petersburg, FL: Great Outdoors, 1963. Print.

Escobedo, Alonso Gregorio De. La Florida. Ed. Alexandra Elizabeth Sununu. New York: Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Espanola, 2015.

Owre, J. Riis. “Alonso De Escobedo and “La Florida”” Hispania 47.2 (1964). 242-50. Print.

Sununu, Alexandra Elizabeth. Estudio Y Edición Anotada De “La Florida”: De Alonso Gregorio De Escobedo O.F.M. Diss. City University of New York, 1993. Print.

Alonso Gregorio de Escobedo, O.F.M. La Florida [ca. 1590-1610]. Draft translation by Thomas Hallock. Copyrighted; please do not reproduce without permission.

Canto 27: This canto contains the way in which Indian witch doctors play with fire, how other Indians fish, and the various ways in which they hunt.

(Folio 334r)

Just as the great craftsman divines

the most perfect gold in stone,

in temptation, all-powerful God tests

the most faithful to see if he is worthy;

and when those tested prove victorious,

God grants a thousand everlasting Mercies,

God grants promised pardons and good fortune,

that one should not die in misfortune.

The perfect stone was the previous canto,

which had as its theme the finest gold:

the virtue of the sanctimonious man,

whose bravery was tested by infidels;

and if he felt some fear, perhaps,

witness how God gave him strength

which was vanquished with the strong arm,

that banishes everlasting Death from death.

(334v)

With God leaving us in this desert land,

and amongst cruel people, as I have said,

that we should always stay on guard,

being in the towns of our enemies, the infidels,

even as we open to them the true door

of divine baptism, which offers shelter,

to those gentiles[1] for them to receive

the Catholic faith upon their death.

A true and righteous road is shown

even to those with fear in their hearts,

who need to be as strong as diamonds,

who seek to advance divine grace, God:

He, who punishes the wealthy, arrogant lord

and who rewards the humble sinners,

providing these pagans would put their lives

in His hands, and become faithful Christians.

Our short life is not much to sacrifice,

for He gave his life on the Cross for my sins,

and for those lost, idolators souls

who dwell in those far western reaches.

If they were to murder their vices[2]

and adore sweet Jesus everlasting,

they would rise to Heaven, victorious,

glorious in their everlasting rest.

(335r)

Oh great Father, I plead to you and pray,

give enough sweetness to my words,

so that the Indian who is most lost

knows the errors of his winding ways,

so that those who have offended may come,

that they can see light through the dark clouds

which that the treacherous deceiver,

Lucifer, the cruel liar, cast before them.

For those who serve the Indians of this land,

then, clear the space in their souls,

surround their spirit with eternal flame,

warm them with a holy peace,

bring them eternal fire in this brutal war against

those who pretend to follow sanctified principle,

those who had never sought your forgiveness,

who are not only sinful, but who sin over sin.

Of witch doctors, there are many,

who choose to enter into battles

juggling the hot flames of their fires,

made for this purpose in their huts.

Those who can handle the fire are

customarily given sacred titles and laurels,

while those who burn themselves lose

their fame and force, their position and place.

(335v)

I was witness to a pitiful case where

a western Indian (indio pontentino) burned himself;

so he could no longer walk, he lost his status and seat,

his knowledge failed, he became wretched and poor.

On the contrary, another was seen as powerful and wise,

coming away from the fire showing dexterity and skill,

having handed the flames without burning himself,

with such skill that the mob took him for a holy man.

So go the deceptions used by the enemy

in the expansive provincias[4] of Florida,

should one of them choose to challenge

the intentions of another one.[5]

These are the tricks ordinarily used

by these murderous (homocida) Indians,

bringing about death death in their blindness,

to the town with their vile promises.

They are a miserable and sinful people.

A people without justice (gobierno) or truth.

A people who worship vile demons.

A people who are all doomed to hell.

A people wicked to the Virgin Mary.

A people without sweet everlasting Jesus.

A people without their natural reason.

A people not like rational human beings.

(336r)

These people live on the beach by the sea,

naked, lacking any kind of clothing,

dressed only by morning rays from the East,

whose warmth gives them all their peace;

but without God, their minds are impoverished,

and lacking the reason given to man,

they dress as they please, jumping in

to swim with the fish at any new test.

It is a fearless nation, and made as such

that with great strength and swiftness,

they swim from the river to the sea,

without showing any sign of fatigue.

In what they have, they do not make

small gifts; in virtue only are they lacking,

and while they are great fishermen

they are not righteous themselves.

When the tide is coming in,

a number of the skillful Indians

enter into the water to start their fishing;

and as the sun sends its light to the earth,

armed with spears, they form a living bridge

that reaches from one side to the other,

and as the water rushes back to the sea,

the fish are left there on the dry flats.

(336v)

Clearly, as experience shows us,

fish out of water quickly die, these are

the laws of He who gives sentence;

the Indians who want to eat seafood

show great diligence in their fishing,

and with the use of handwoven weirs,

that are made just high enough

to keep the fish from jumping out.

The number (copia) of fish is so great,

that the Indians take with their skill,

that I must praise them for their efforts.

It is one of the best things I have seen

to show a proper instrument against vile vice,

to occupy themselves in fishing, for those who

choose not to atone for idleness upon their death.

The ponentinos[6] have another method,

where they take the net in each each hand,

taking in their catch with a continual motion,

trawling through the salty, brackish flats.

Wandering like pilgrims in this way,

the fish cannot escape because

of the dry spot in the narrow gate

they have built in the shallow pools.

(337r)

In the afternoons the generous fishermen

they share their catch amongst the poor.

In so doing, none of them are cowardly,

none of them act misers to the poor.

The beloved nobleman burns with a flame

that rescues and redeems those in need,

because he feels the hunger of those afar,

and the suffering of another is his own.

It is as they had objects of faith,

these lost souls would then be found,[7]

but because the vile devil awaits them,

they will find themselves nestled in eternal fire.

Were they to convert to the Roman faith

the wages of the sin they have committed

would be absolved by true penance,

and their souls cleansed from sorrow.

It is so that these traitorous infidels

who have been kept in shadowy darkness,

with the delight that my soul adores,

may be brought to the light of justice.

Can a town that treasures idolatry,

and that is always lined up for war,

in the soverign God find solace?

With baptism and the Christian faith: Yes.

(337v)

The lord of the vineyard arrived at daybreak,

and again at tercia, between sesta and nons,[8]

to gather laborers. And while some careless

late arrivers put themselves ahead of the others,

ahead of those who gave less time than the others,

the first were paid just as the last were paid,

leading the workers who had come earlier

to complain and plead their case to the Lord.

The Lord Said: “Friend, if the money is mine,

well enough for me to pay the last

just as the first; you speak madness

in complaining about your wages.

Take what I, your Lord, have given you

quit this vile plague of jealousy,

I do not pay fairly, or so you judge,

but for those who judge, I pay enough.

The Lord of this vineyard is all powerful God,

which is the Roman Catholic Church.

The worker is the religious community

who professes the blessed Christian law.

The last is the seditious Indian, who

keeps to the infidel’s empty sects;

but if the Indian who is as true as the first

he shall be paid with the palm of truth.

(338r)

Because they often have their arms ready,

they go to dry fields and light them on fire,

where there are herds by the thousands

of small rabbits, which the Indians hunt avidly,

some coming into the the hunter’s arms scorched

others blinded by the steam and smoke;

some meet their end in the high grass,

and others, killed by skillful archers.

Having a tremendous lack of food,

without the care of cattle and hogs,

the Indians and Spanish, to their satsifaction,

kill rabbits, ducks and geese;

and the unfaithful Indians arrive at the seat

of our leaders on the festival days

with the intention to split, hoping to sell

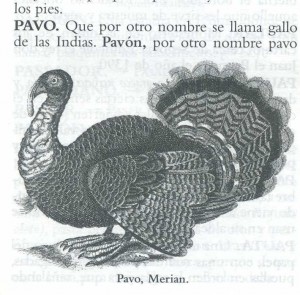

not just their fowl but their pavo real.[9]

They value a bird called “montesino”

(which they raise in abandoned fields,

and is killed with an arrow by the ponentino

or by our loyal soldiers with a bullet)

priced at fifteen and a half reales of fine gold,

for the taste of this fowl is greatly valued;

one bird for one real, or two for the rabbits,

is plenty enough for the man who is famished.

(338v)

They often tear through the hills (montes),

skillfully, following the most narrow paths.

The speed of the light-footed dear

avails little against the far swifter arrow;

it flies straight through the life-giving heart.

The fleet deer proves to be no match,

and with the second shot it dies,

taken down by the hunter’s homicide.[10]

They take great quantities of game,

which is esteemed by all soldiers,

and the skins (gamuzas[11]) are of better quality

than what is made in the land of venison.

The Spanish gentleman, of noble race,

hunts them in the remote hills,

leaving behind the ease and the luxury of court

to suffer from rains, from wind and the storms,

They make a morish boot, the famed

borcequí, which I have seen for myself

as worn (calzar) by noble gentlemen,

who shoulder it like a great cape;

in this way, it was worn by the admirable

Pedro Menéndez, general and friend,

a prudent man, a worthy man, haughty

when led to be and calm when at ease.

(339r)

In La Florida, doublets customarily sell

for three ounces of Mexican silver;

and these are cut at half the length

of the doublets worn by Spaniards;

with these the Spaniards do not lose their life

to the lost idolators, infidels and pagans,

for without them, the Indians would kill

even the fiercest, rugged and strong Spaniard.

And upon my word, I write the truth:

that these doublets cannot be

pierced by poison arrows, even

when launched by a powerful hand,

the skins are folded over eleven times,

so that the Spaniards goes bravely

into battle against the Indians, who

strike, always, with a steady hand.

When the arrows strike a soldier

in the chest, he breaks them,

giving repayment with bullets,

not letting their arrows be used again.

From this the Indian feels a rabid disgust,

he is consumed with burning rage,

he is no longer to bring about their death,

because his arrows have been broken in half.

(339v)

Were they not broken, they would hurt our friend.

The unruly Indian (cimmarón), our enemy,

would make use of the unbroken ones,

gathering up the sharp arrowheads.

If they gathered them, I am faithful witness,

they would restock their empty quivers,

and return again to the field of battle

against our soldiers who dress in mail.

That is why our soldiers our soldiers

break them, as I carefully explained;

by doing so, they break the thread

of intent of the swift Indians,

who always sharpens the arrow points;

to bring death to our faithful soldiers,

with those arrows that fly straight

to their eyes or head, chest or neck.

An Indian from this fierce nation, full of vice,

will sometimes kill the faithful Christians

by burying his entire body in a field,

making a great[12] sepulcre in the sand.

With the bow and flying arrow

in his hand, he waits for the sound

of footsteps of some poor traveler,

who by his bad fate, is caught unaware.

(340r)

The Spaniard and the Indian then return,

after the armies have finished their war:

the faithful Christian to his pernicious games,

and the unfaithful to their task of fishing;

and to their idolatries, being blind men;

and to their hundred whorehouses, their squalid vice;

and to all below, which with my pen,

which will be recounted, in brief sum.

Now they kill cranes, geese and ducks;

now the ducks which I called montaraces (turkeys);

now they pull sweet potatos from the soil;

now they harvest the mounds of beans;

now they busily hoe the savannas;

now is the time, between war and peace,

now to sow their maize for food,

which gives them life because of God.

Now they sow melons and squash;

now they water the fields they have sown;

now they gather heaps of watermelons;

now they grind the corn that was toasted;

now they gather great quantities of shrimp;

now they fish for skates (lizas); kill the flounder (lenguado);

and hunt corvinatas[14] with arrows,

in this way, satisfying their hunger.

(340v)

And though it may seem rough,

what I want to say to the Castillan

to not believe me would be quite rude,

so I swear by my faith, as a Christian,

to the truth: of the deed I describe,

there are notarized and sworn witnesses,

whose signatures are there to certify,

for anyone still who is not satisifed:[15]

how they wade into dangerous seas (charco)

to hunt and kill a full-grown whale;

and alone, the brave and strong Indian,

seeking to deprive the whale of its life

dives with great fury on top of it,

until he has worn the whale down;

he holds on, and if luck goes his way,

he brings about the poor whale’s death.

With great speed and agility, he takes

two stakes and, using a club,

drives them into both ears, harpooning

them with obvious courage and skill.

If everything goes according to plan,

and the whale is given furious chase,

others approach in their canoes,

tying up the whale with ropes

from both sides of their canoe.

(341r)

If the stakes stay fixed on their target,

and if they remain stuck in the ears,

the Indians pilot their canoe

as if it were tied to a fortune

It is a lesson learned from their ancestors:.

that if the ears remain covered, in time,

they can make it to the beach,

with no escape for this ferocious beast.

They deprive this whale of its life,

and as I have said, if their luck holds

they share this rustic food along

the sandy shores of the sea,

and it is believed by all that[16]

this food gives strength and life,

and these ponentinos being without bread,

eat this, continually, in its place instead.

It appears that the whale has its home

along these smooth and sandy coasts.

The excrement is turned into ambergris[17]

which refreshes (refrigera) the human nose.

Gentleman of great intelligence and skill,

as well as the gallant and courteous lady

appreciate giving off such a scent,

esteemed by kings and gentlemen.

(341v)

These primitive (natural) Indians

carefully search along the shores,

and knowing how precious is the scent

walk back and forth, a thousand times.

They gather great quantities avidly,

for when a ship passes near him,

the passing Castillians give them

beads made of glass as payment.

It is such, the fragrance that spills

from this precious, fine amber

for the genteel, well bred Spaniards,

that when the unworthy Indian[18] brings it,

he burns in ardent, amorous flames

eager to give this gift to his master,

bringing to his lord that treasure

more precious than pearls, gold or silver.

They approach in woven boats (canoíllas)

surrounding the sailors on both sides,

with hopes that the ship strikes a shoal,

bringing death to the faithful soldier.

He is not able to meet the challenge

as the Indian here appears to be calm,

in his false bearing, detestably tame,

while inside, hellishly violent, abominable.

(342r)

Oh, the poor ship that nears the shores!

There, sailors will come to see naked people,

in canoes paddled faster than post horses

by this nation, as blind as it is stupid.

Our men pay dearly on this coast,

and when taken captive, are struck dumb,

amazed by those who practice idolatry,

and are such rabid enemies to Christianity.

But if they could see themselves as inferiors,

then they would come to ask for forgiveness.

We have seen it ourselves from these traitors,

and look away from their beastly dementia.

From the fury they show our gentlemen,

thus, we offer only with gracious resistance;

we do not seek to avenge the deep malice

of those greedy ones who wish us dead.

Dressed as sheep on the outside,

they are blood-thirsty wolves within:

these savage horrible, and fierce infidels

board our boats before we can drop anchor.

Without waiting for the anchor to set,

the captain, pilot and sailors

take what is offered for ambergis

greedily paying the pagan’s price.

What the sailors trade aboard the frigate

does not hold hold the same value,

or worth (fundamento) as the ambergris,

which is coveted more than I can recount.

Neither pearls, nor emeralds, gold or silver

can equal the ambergris in its qualities.

The Indians exchange at one hundred to one,

and leave contented, with no suspicions.

When given something like scissors,

they regard it as the richest treasure,

and likewise for a large spoon, which

they would not barter for pounds of gold,

more than the cutting board of a loom (cortadora);

in greater esteem than the Moor for Allah,

they love a fish hook, whether large or small;

it is more valued than heavenly God above.

It is the fishhook that gives them life,

it is what gives them the greatest joy;

it is what brings food, nourishment,

to the Indians, strong and weak alike;

he, who amongst the faithless,

leaves the bargain without goods;

if the western Indian, most courageous,

is left lacking, he is sad and weeping.

(343v)

They lack maize, having no grain,

for being on the dry, sandy coast,

these pagan barbarians are left

to feel the pain of what they need.

They eat only in Winter and in Summer,

as I have said before, from the whales,

or from what they catch from hook and cane (caña),

in the waters bathed by that golden sun.[19]

Although it is true, what I have declared

in the present canto, there are great quantities

of fish that the Indians take in

the province where I was in attendance.

There are no limits in gathering ambergis

from when the sun gives light to the day,

they fish in coves, with canes and with weirs,

catching many trout and delicious eels.

I can say this, because I was witness:

on the treacherous costa de Carlos,[20] where

I was on one of our own small ships,

one long night, in a dangerous pass,

while coasting the rocky shoreline,

the winds would not come to rest

winds howled from the northwest,

and even the most valiant was afraid.

343(r)

We did not haul in our iron anchor,

and as the sun brought its golden light,

we were grasping two thousand trout

by the neck, with many more dorados;

and lacking salt in these remote regions,

the captain ordered his soldiers to cut open

the fish. They were dried in the breeze.

They gut the fish immediately,

and over fifteen days by my count,

and we went hunting along the shores

of the formidable looking sea,

while a corsair, seeking to make landfall,

was robbing upon the high seas

silver from our faithful Christians.

I was Chaplain for our people,

who professed from their hearts,

upon death to avenge the insolent.

The most cowardly of them showed

great courage, to great satisfaction

And here I will promise to proceed,

continuing tomorrow, on this theme.

Canto 28: This canto contains the manner in which the caciques keep the loyalty of and do well for their vassals, how the Indians play the ballgame with their feet, how they bet on foot races of two leagues, and the manner in which they bury their dead.

(344r)

The moring rope that binds the Jarama bull,

and greedy men to their treasures of gold,

and the lazy to their precious bed,

and the monk to his perfect state,

and the doncella to her reputation,

and the bishop to his blessed bishopry,

and the good word of the well born man,

here the shame of being false to one’s word.

Where there was none, I will describe

in detail the infidel town of Florida,

as I promised to the prudent reader,

the rites and customs of their life,

where you will see how diligently those

from enlightened nation of Spain brought

the mercy of God, the sweet sovereign,

the light of clear faith, and Christian law.

(344v)

If God should want the same Mercy for

the Indian, as the worthy Spanish has,

granting the light of Faith, I believe he would live

by our same sanctified Christian law;

for while he wanders blindly without light,

he pacifies by loving his neighbor,

and he freely gives what is asked of him,

and with good words, begs well of others.

There are signs to indicate what I claim,

that he would choose to serve God

with care, even if he is presently

God’s enemy, dying in sin as idolator;

and it is my opinion, I can testify,

that the cacique is respected by all

that he proves with his works, quite clearly,

what I am saying to the wise reader.

Around his house, he sows a field

more than a league wide and long.

From this field comes his own sustenance,

and by those in his house or under his care,

no thief violates what is his possessions,

not a grain is stolen from his fields

until he who is lord and author (autor)

gives license for the town to enter.

(345r)

As Apollo unfurls the warm rays of the sun,

the town cryer sends out a high shout,

“To all people, come gather the maíz,

from the first Indian to the last,

that the cacique, your beloved lord,

consents to share with all, I demand of you,

when I cry out again, grab ye your pitchfork,[21]

from he who gives, come, gather your corn.”

And so the Indians leave their homes,

with great agility, as you would think,

they follow deer trails and well worn paths

to go and reap the grain. Carried from hunger,

they people are delivered from hunger,

they are given good sustenance,

and as this maize serves to survive,

so their their lord gives to them life.

Watch how these villainous rustics eat,

stop, look at them, and consider:

how they take the maize in both hands

and swallow the entire cobs whole.

There is no hound, mastiff nor bulldog,

Nor bear, nor carnivorous lion

that devours so greedily, unchecked,

like skeletons who have lost self-respect.[22]

(345v)

With great rejoicing, with great smiles,

they take, until the second cry sounds,

signaling in their mother tongue, that if

they take any more, they will face great penalites.

They do not leave the corn fields until

a cry is heard, but then, with serene faces,

they go, though each of them to recognize

that the mountain of maize is much smaller sized.

What can be carried, they take home

to eat little by little, although here

I misspeak, for scarcely a cup is left;

these crazy Indians know no moderation,

they lack reason, do not save for leaner times.

What I say impinges their honor,

how these poor men suffer in misery,

because they do not plan more carefully.

For that unfortunate occasion that

tomorrow brings, he will not consider,

as would the more prudent, cautious,

wise, discerning or careful man;

He cares for the present, impertinent,

regardless of what tomorrow will bring;

the varón, who want to live, avoids deprivation

while the Indian often dies of starvation.

(346r)

I am in admiration of the compassion

that burns in the Pagan’s breast.

If brought to the Christian faith,

tt would be a tremendous blessing.

Oh, how many in the lap of the Church

that give alms, but with bitterness.

Here we see, in the cacique, documented

how one gives with the greatest contentment.

But because they lack the true Church,

they are inferior to the Faithful,

and in misery, impoverished, lost,

on par with all who are impoverished.

What an extraordinarily happy turn of luck,

were they to turn from the error of their ways,

and to come to know all-powerful God

and come to follow, these people, his Laws.

They play a ballgame, that if I can give,

a proper account, it would be a pleasure:

Twenty on twenty, on opposing sides,

each with great athleticism and force,

the person carrying the ball stays sharp,

and plays with such poise. There are

no rules on the field, and come evening,

one can see not where the loose ball is going.[23]

(346v)

They skillfully fix a pine tree in the ground,

more than ten estados (fifty feet)[24] in height,

and on the very top of which, with dexterity,

they place a figure in a kind of straw cradle.

All forty of the players take, with great skill,

to the field, where they prove their madness

where, by the rules of this sad game,

they inflict on others unceasing pain.

The game usually last an entire month,

although they return to play everyday.

The one who serves the ball, merrily

tries to move about in various ways,

while his strong opponent move swiftly

to block him with a tackle (porfías),

shoving his hands out in front of him

because his feet does not leave the ground.

While those two go free, as I am saying,

the other thirty eight make war;

each one choosing his enemy and with

strong arms, throwing him to the ground.

If one of them helps his friend

by grabbing the ball in his right hand,

the others complain to the chief,

and he must leave, and never return to, the game.

(347r)

The two valiant squadrons carry on,

fighting as if they were in battle,

subjecting one another to the capture

of their enemy, until the fighting stops.

The armaments of these arrogant Indians,

which are their steel breastplace and finest mail,

are their own formidably strong limbs,

who (on the other side) they want to crush.

While in Castilla they compete with their hands,

the Indians gallantly play with their feet,

with the ball following the right way

of the player with the strongest, quickest feet;

and when the goal is signaled, regardless of time,[25]

fifteen points are made, no argument or complaint;

and then they come to have a hundred,

the game ends, the points are all scored.

The Indian, who by fate finds the ball

in the hands of his posession,

generates such hostility with his play,

people go like blind and crazy men;

on the opposing side, full of malice,

struggling to deprive him of his poise;

his purpose being, thus, to jam

the moves that his opponent plans.

(347v)

The teammates of the player with the ball

battle mightily against their opponents.

The fight, heedless of family,

without respect to brother on brother,

nor father on son, it makes no difference.

One player may try and help, but in vain,

interfering, as the player attacks his opponent,

trying to break up the scrum, and in this way,

he seeks vengeance against his enemy.

If one player slides off to one side,

the opponent darts across and grabs him,

blocking him, in this ballgame, in the same

manner in which the Indians make war;

and as he sees the time running short and (vario?),

the player with the ball in his hand

raises his naked foot from the ground,

hollers the signal for goal from far off.

And when the Indian sounds the signal,

his friends holler shouts of joy;

by hitting the target, valliantly,

their team claims the victory.

The other players, furiously mad,

refuse to lift their eyes all day,

upon seeing that their game was lost,

they feel, in their soul, tremendous loss.

(348r)

Those who play,[26] use what they have

for currency, some fish bones (oserzuelos),

but are valued in Castilla at a filthy cornado[27]

but for them are the principal treasure.

For this scant change, the most renowned

and valorous Indians dance about:

for he who has won receives great graces,

and how is the loser valued? Disgrace.[28]

As the darkness of night begins to fall,

The people split apart, without sanity or law,

trading blows, fighting, with one another,

sometimes they crack open bloody noses.

Others crying, with thousands of pains,

showing the certain, the obvious signs

that they are feeling great discontent,

so great is the pain they hold inside.

They return home, flush with emotion

but empty handed, without gifts,

such is their sad and miserable state,

so being bad and poor people;

some fear for their own death

and cry out, without pause or intervals,

against the pain by which they are oppressed,

that strangles them, which they must suppress.

(348v)

Some of those Indians, miserable are they are,

seek to prove their fame on occasion and

will by their own choice and pleasure,

imitate those brave cimarrones, the Timucuan,

whose courage and spirit they use in their play

with clubs (macanas), or to say heavy sticks,

so that, when an enemy should come about,

he is not ignorant of the way out.

Others shoot arrows at their mark,

and hitting their target at one hundred paces,

they give such a great shout and cry,

that it carries across the brisk breeze.

They show contentedness, joy and pleasure

on seeing an opponent (traidor) to their touch,

because if the Spaniards make themselves merry

they lose their force, or if not, recover it.

Some fight each other, chest to chest,

to demonstrate their fortitude and strength,

so much do the Indians esteem their own strength.

and speak very highly of his own skills,

If the strength of a soldier is worthy,

the Indian will brag about those vile deeds

but in the point that reason sends him,

his life he will take, from the demand.

(349r)

Others, with great force in their arms,

throw great pieces of iron (barra) stones;

others rip apart the knot in a pine tree

to see who can tear their way to the center;

others, with no regrets or obstacles,

climb the shoots of a grape vine;

others spear birds in mid-flight,

and later, eat these birds with delight.

Others run a distance of two leagues

without stopping in fields nor in plains,

and while the victory brings little gain,

less than a real for each run;

it is plenty, what they gain in bragging rights,

the members of this valiant, sinful and fierce nation:

a wonderful crown of palms and laurels

is won, and placed upon the winner’s head.

The poor Indian runners come,

covered in sweat, and they cry out,

in a thousand shouts and cries, as the

fatigue presses them, showing in their faces.

Their bodies are racked by a thousand pains;

to reach the end, they had prepared themselves

with a remedy that they use, but are lucky,

because this remedy could cause their death.

(349v)

And while it would seem to be bad for them,

the runners are kept healthy in this manner,

how they ordinarily care for them

would typically kill their runners;

this extraordinary (potísimo) remedy

is what the runner appears to wait for,

although it strikes me to be one

that the whole world would laugh at it.

The women wait right until

their gallent hero’s return, then they

drench the sweating athlete in water,

the water cooling the runner’s passions.

The women do this, showering the runner,

who wears a white shirt and lies on his mattress,

and here they remain, bold and content,

valient, undaunted, and strong.

And when the sweat has been washed off,

the fleet Indian takes on a new wager:

he will run with the most agile warrior,

even thought is it the middle of siesta.

He is given sea water,

brisk, invigorating and strong —

the winner make merry with his children and wife,

finding contentment, always, in his skill.

(350r)

If the principle cacique comes to their home,

a cacique with great fame and tribute,

some Indians will seek out the dainty nuts[29]

the same used to fatten a bristly and suckling pig.

and make gacha, a prized dish

that they can serve without shame;

they make it beforehand, so they have some

to feed the cacique when he comes.

They make great quantities of the dish,

which is not only small but bitter,

they gather up acorns (bellota),

carefully removing the bitter shells;

although they grind the acorns for a long time,

the labor does not bother them,

they eat this dish with great gusto.

They make a hillock (sepultura) for

the ground acorns, burying them while

the most ardent rays of the lovely sun

come from the East, at about noon,

and because the coldness damages them,

they simmer the dish in hot water;

it is cooked this way, in the soil,

that the torta de gacha comes out whole.

(350v)

The soil and water give a flavor

to the acorns (fruta) to which I refer,

so they eat with no small relish (sin disgusto);

the principal caciques of Florida sends

some to the most strong and robust laborers,

typically giving them some to eat,

because this gacha, dedicated to the chief,

is by all Indians most highly esteemed.

The principle Indian is so poised

that one will never, ever see him

eat too much, or with mouth open,

like the more gluttunous will eat;

even as hunger has fatigued him,

discretion keeps his passions in check;

he gives no signs of showing weakness

but shows how he is strong and courteous.

Other Indians walk for ten days,

carrying only toasted corn flour,

crossing high and remote mountains

with a steady and speedy step,

only to bring back valuable leaves

from the tree, as I have said,

which is called cacina in the West,

brewed and valued by all as the best..

(351r)

Far more than the finest gold

do they value this precious little tree;

the principle chief, the nobility,

brew it in their homes always,

and they drink it, with relish, like wine

because the tea has a marvelous flavor

and gives strength to those without vigor

even when they are weakened by hunger.

Also, they make with the ashes

a very tasty corn dish, gachuela,

which they leave out until midday,

for all to eat who come to their home.

There the brave fighters before disputes,

these attentive, vile rustic townspeople

they go the food that has been prepared;

against their vile enemies, off to make war.

And the moment they enter the house,

they sound a horrible, ferocious yell,

that pierces all the senses, so that

no one dares look upon them,

but without delay or skimpy hand;

they help themselves and do not rest

until they have taken in the middle

of the house this smooth, valued dish.

(351v)

Eating the gacha, shellfish and good fish,

the brave soldiers satisfy their hunger,

tribute is always made from the heart

in rations, to which soldiers are due.

It is an ancient, age-old rite

to give sustenance to those Indians

among them, who are leaving for battle,

against our own, who are wearing mail.

These valiant soldiers wear the scalps[30]

of the Spaniards whom they have stripped of life;

the heads of the honorable Christians

hang from their legs as from a garter.

They are the Guale Indians, a ferocious nation,

unlike others that have been seen in Florida,

they are different: their faces are lined

with tattoos, showing their ferocity and force.

Those most fortunate, the most valient,

whose faces are etched with designs,

parade through the plaza with all

people present, to have respects paid;

and those who wear their garters amongst

these people are the most celebrated,

the most courageous race in their land;

they are chosen to war against Spain.

(352r)

When the Indian is asked, “tell me, poor soul,

why do you not want to become a Christian?”

The poor ponentino (westerner) responds:

“Because the devil smacks me with his hand,

and says to me, “traitor, miserable whelp,

do not believe what the Castilian says.

Accept my deceptions, because if you do,

great favors, if you believe, will come to you.”

And when some of them were baptized,

and as they tore off their vestments,

they returned to their corrupted rituals,

leaving what brings glory and peace,

And if someone says: “Damned souls,

why not use your gift of reason —

and why not forget Jesus, sweet Lord,

and love instead the tyrant Lucifer?”

They respond as such: “if we accepted

the law of God, the cause was the clothes.

But later, señor, we tore off the clothes,

putting your rites out of our heads.

We returned to our old ways, finding

contentment in what we were born with,

and we stopped cutting our hair.”

Indian customs, so evil and fierce!

(352v)

Upon dying, passing from this life,

the Indians are placed in a sepulchre cave,

and in that cave, they leave food,

so their dead may have plenty.

Being so united with the devil,

death takes an even uglier form:

these barbarians are absolutely certain

that the dead sinner still feels hunger.

The possessions of the deceased

are buried in a deep cave with him.

No one would dare touch his things,

instead all pay respects to the grave.

They mourn, they mark the death,

in the coutryside, mountain, fields and plains,

where tears are shed for the poor decased,

without missing even a single day.

Each morning for an entire year,

they cry to the sinful ponentino,

and as a custom, as their ritual and rite,

they cover themselves with ashes continually.

The Devil, being a great teller of tales,

whispers words sweet on the surface,

enters into the cadaver and consoles them,

revealing four thousand lies to them.

(353r)

And the laments stop when mourning finishes,

and by choice, they return to their homes,

and they grind the corn for sustenance

that was toasted over the coals,

and they eat gladly, with the ashes,

or by another recipe, the women mix

the dough with warm water to feed them,

which like our bread, gives sustenance.

And it gives great strength and vigor

to those who eat it, as I have said,

that the pure white bread made from dough

by the woman who are friendly to our side,

although the method always straightens up

the health of the cruel enemy,

by bringing so much blood to the human body,

that thousands of tumors born by summer.

In particular, the bread does harm to

our Spanish people, who are used to

eating wheat bread that has been leavened,

although there is great poverty at home.

But if one is in need, his hands are tied,

he will eat the Indian bread in a pinch,

although he will not devour such food

but eat only so his body will survive.[31]

(353v)

After a while, one will feel sick and

weighted down from eating this heavy bread.

It is such bitter and disgusting food,

making anyone who eats it angry.

If a person does not lighten his veins,

the blood in his body will raise up,

suffering such damage to this health,

that death will come by this instrument.

I promised the previous day to provide

an account of a certain war that

the true and valient Spaniards waged

against the French who came to their country,

who came to Florida with such insolence,

intending to be thieves, as from my quill

in another canto, recounted here still.[32]

[1] gentil: “The idolator that had no knowledge of a true God, and worshipped false idols” (Sebastían de Covarrubias Horozco, Tesoro de la lengua castellano o española, 1611).

[2] homicida: a favorite end rhyme for Escobedo, implying spiritual death. Covarubbias quotes John 8:44, “Ille homicida erat ab initio ….”

[3] Hechizar: Use image, “hombre hechizado,” from “Hechizar” in Covarrubias.

[4] provincias de la gran Florida: by “provincias” Escobedo would mean “colony,” and by la gran Florida a tremendous expanse, stretching from Key West as far as (by some maps) Nova Scotia.

[5] “si manifiesta de unos ser contrario / a otros de favor en esta vida”.

[6] “Poniente“: “The part of the the sky from where the sun darkens in the other hemisphere, beyond the horizon … another part of the world” (Covarrubias); Escobedo means tose from the far side of a sunset, or “westerners.” With the usage, a favorite of his, Escobedo also anticipates the following homily from Matthew 20:16, “he who is first shall later be last. ”

[7] “Si como tienen obras fe tuvieran / fueran de lost llamados y escogidos ….”

[8] tercia: the third part of the day in canonical hours, between the sixth hour (sesta, midday) and the ninth (nons) hour, or 3:00 pm.

[9] “pavo real“: turkey, as illustrated by Covarrubias, although the real following pavo also puns on the Spanish currency (un real). The discussion of the turkey, or “montesino” (thing of the woods) continues in the next stanza.

[10] Again, Escobedo puns on “homicida”: “ … pues al segundo salto de la vida / al indio cazador que es su homicida”.

[11] gamuza: “a type of mountain goat … whose skin is tanned to make breeches and “jubones” (vest?) (Covarrubías).

[12] gran: “great,” by common usage, but possibly ironic. Covarrubías defines “grande” as not only the “opposite of small” but a “title of great honor.”

[13] boniatos: note on sweet potatos?

[14] corvinatas: perhaps sea bass; Falcones has mullet.

[15] Following Escobedo’s concession, Sununu includes corroborating accounts by Nicolás Monardes Alfaro, Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (1565) and from José de Acosta, Historia natural y oral de las Indias (1590). Covington and Falcones speculate that the Indians wrestled pilot whales or (less plausibly) manatees (153n).

[16] “Y es tenida de todos por tan buena ….”

[17] In a long discussion of the subject, Covarrubías also asserts the belief that ambar, a “paste with extremely smooth odor,” was made from the “excrement” of a whale.

[18] Escobedo puns, in line 8, on “indigno” to also suggest “Indio.”

[19] On the availability of food, Escobedo contradicts other stanzas (Sununu 2:896n).

[20] Probably the coast of Fort Myers (Sununu 897n).

[21] “porné en la horca”: porné being an antiquated form of pondré, or take.

[22] Sununu has “porque a razón perdieron el respeto”; the manuscript, she notes, reads “arrazón” (2:903 taken here for “armazón,” or skeleton.

[23] “ … su pelota va siendo arrojada”: more literally, the ball goes about unpredictably and with force.

[24] Estado: measuring roughly the height of one man (Covarrubias).

[25] “dando en la señal, tarde o temprano.”

[26] “Los que juegan”: perhaps, “those who gamble on the game?”

[27] Cornado: fifteenth century coin, valued at one tenth of a maravedí; Covington and Falcones have “copper coin” (149).

[28]In the stanzas closing couplet, , Escobedo uses his favorite tropes of chiasmus and repetition: ” … por ganar, que quien gana, gana honra, / y gana el que perdió, suma deshonra.

[29] frutilla: probably acorns, although Sununu defines gacha (below) as a dish made from corn and honey, or what would be like the traditional softee.

[30] “Estos valientes traen la caballera / que al español quitaron con la vida ….”: Covington and Falcones translate this stanza to “These men wear on their legs, as if they were garters, the hear from some Spaniard who they have killed (151).

[31] Escobedo puns again on a favorite word, “homicidia”: que no va largando a tal comida, / por no ser de su cuerop el homicidia” (2:923) .

[32] Canto 29 recounts the efforts of French Huguenots to settle in Florida and the orders by Felipe II to Pedro Menendez de Aviles to attack the French.