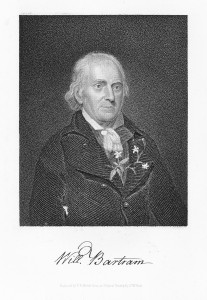

From his early years, William Bartram (1739-1823) was steeped in the complexities and finer points of plants, as his father John cultivated an extensive garden at his Pennsylvania home, still open for visitation today. William was free to roam the gardens, and honed a talent for illustrating plants and birds. Upon being appointed botanist to the King in 1765, John Bartram headed an expedition to the newly acquired southeastern colonies, taking William with him. The younger Bartram, then twenty-six, already had an encyclopedic knowledge of the field. He would return to explore Georgia and Florida less than a decade later as part of a trading expedition, against his father’s wishes, but in pursuit of his own desires to capture Florida through vivid descriptions and lively illustrations.

From his early years, William Bartram (1739-1823) was steeped in the complexities and finer points of plants, as his father John cultivated an extensive garden at his Pennsylvania home, still open for visitation today. William was free to roam the gardens, and honed a talent for illustrating plants and birds. Upon being appointed botanist to the King in 1765, John Bartram headed an expedition to the newly acquired southeastern colonies, taking William with him. The younger Bartram, then twenty-six, already had an encyclopedic knowledge of the field. He would return to explore Georgia and Florida less than a decade later as part of a trading expedition, against his father’s wishes, but in pursuit of his own desires to capture Florida through vivid descriptions and lively illustrations.

Commissioned by the London physician John Fothergill to survey the land and catalog the flora and fauna, Bartram rambled through the southeastern colonies of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Alabama from 1774-1777. He filled the pages of journals with notes about the landscape, encounters with its inhabitants, and his reflections on what moved him most. He sketched quirky birds and sinuous plants. The result of his journals and letters was a book known as Travels, published in 1791, and circulated widely in the US and Europe.

William Bartram often pauses in his Travels to list the variety of plants and animals that grace the landscape, and these moments can read as some private aside for the science-minded or botanically savvy. Just beyond the foreign cadence of Latin, we meander alongside Bartram as, in this selection, he describes the peaceful Alachua Savanna (Paynes Prairie State Preserve, near present-day Gainesville), its inhabitants, its lush fringes and phases and songs. His interactions with the Indians living in Cuscowilla (present-day Micanopy) reveal to him their resourcefulness and deep appreciation of their natural surroundings, and he is especially sensitive to their presence as conflicts between the natives and the English had erupted during this particular trip. In this selection, and throughout his work, he often portrays the natives with sympathy and dignity. But his most profound points reflect on what individuals can learn while exploring the mysteries of the landscape. Bartram had been trained in the microcosm of his father’s garden; his venture into the wider world gives him a deeper understanding, as it does for any true traveler. His aim to survey the flora and fauna led to moments of peril and unutterable beauty.

Edited by Shelbey Rosengarten, Assistant Professor, St. Petersburg College and PhD Student, University of South Florida-Tampa

Suggested Reading

Bartram Trail Conference [website].

Bartram, William. Travels through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws. Philadelphia: James & Johnson, 1791.

From Travels (Part 2, Chapter 6)

WE soon entered a level, grassy plain, interspersed with low, spreading, three leaved Pine trees, large patches of low shrubs, consisting of Prinos glaber, low Myrica, Kalmia glauca, Andromedas of several species, and many other shrubs, with patches of Palmetto. We continued travelling through this savanna or bay-gale, near two miles, when the land ascends a little; we then entered a hommock or dark grove, consisting of various kinds of trees, as the Magnolia grandiflora, Corypha palma, Citrus Aurantium, Quercus sempervirens, Morus rubra, Ulmus sylvatica, Tilia, Juglans cinerea, Æsculus pavia, Liquid-amber, Laurus Borbonia, Hopea tinctoria, Cercis, Cornus Florida, Halesia diptera, Halesia tetraptera, Olea Americana, Callicarpa, Andromeda arborea, Sideroxilon sericium, Sid. tenax, Vitis labrusca, Hedera arborea, Hedera quinquifolia, Rhamnus volubilis, Prunus Caroliniana (pr. flor. racemosis, foliis sempervirentibus, lato-lanceolatis, accumunatis, serratis) Fagus sylvatica, Zanthoxilon clava Herculis, Acer rubrum, Acer negundo, Fraxinus excelsior, with many others already mentioned. The land still gently rising, the soil fertile, loose, loamy and of a dark brown colour. This continues near a mile, when at once opens to view, the most sudden transition from darkness to light, that can possibly be exhibited in a natural landscape.

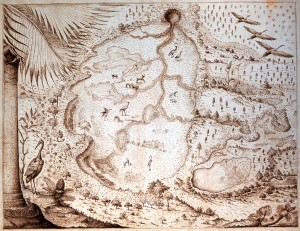

THE extensive Alachua savanna is a level, green plain, above fifteen miles over, fifty miles in circumference, and scarcely a tree or bush of any kind to be seen on it. It is encircled with high, sloping hills, covered with waving forests and fragrant Orange groves, rising from an exuberantly fertile soil. The towering Magnolia grandiflora and transcendent Palm, stand conspicuous amongst them. At the same time are seen innumerable droves of cattle; the lordly bull, lowing cow and sleek capricious heifer. The hills and groves re-echo their cheerful, social voices. Herds of sprightly deer, squadrons of the beautiful, fleet Siminole horse, flocks of turkeys, civilized communities of the sonorous, watchful crane, mix together, appearing happy and contented in the enjoyment of peace, ’till disturbed and affrighted by the warrior man. Behold yonder, coming upon them through the darkened groves, sneakingly and unawares, the naked red warrior, invading the Elysian fields and green plains of Alachua. At the terrible appearance of the painted, fearless, uncontrouled and free Siminole, the peaceful, innocent nations are at once thrown into disorder and dismay. See the different tribes and bands, how they draw towards each other! as it were deliberating upon the general good. Suddenly they speed off with their young in the centre; but the roebuck fears him not: here he lays himself down, bathes and flounces in the cool flood. The red warrior, whose plumed head flashes lightning; whoops in vain; his proud, ambitious horse strains and pants; the earth glides from under his feet, his flowing main whistles in the wind, as he comes up full of vain hopes. The bounding roe views his rapid approaches, rises up, lifts aloft his antled head, erects the white flag, and fetching a shrill whistle, says to his fleet and free associates, “follow;” he bounds off, and in a few minutes distances his foe a mile; suddenly he stops, turns about, and laughing says, “how vain, go chase meteors in the azure plains above, or hunt butterflies in the fields about your towns.”

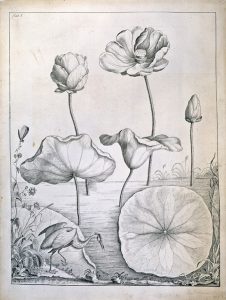

“Nymphea nilumbo” or water lilies drawn by William Bartram (Courtesy, Natural History Museum)

WE approached the savanna at the South end, by a narrow isthmus of level ground, open to the light of day, and clear of trees or bushes, and not greatly elevated above the common level, having on our right a spacious meadow, embellished with a little lake, one verge of which was not very distant from us; its shore is a moderately high, circular bank, partly encircling a cove of the pond, in the form of a half moon; the water is clear and deep, and at the distance of some hundred yards, was a large floating field (if I may so express myself) of the Nymphea nilumbo, with their golden blossoms waving to and fro on their lofty stems. Beyond these fields of Nymphea were spacious plains, encompassed by dark groves, opening to extensive Pine forests, other plains still appearing beyond them.

THIS little lake and surrounding meadows, would have been alone sufficient to surprise and delight the traveller, but being placed so near the great savanna, the attention is quickly drawn off, and wholly engaged in the contemplation of the unlimited, varied, and truly astonishing native wild scenes of landscape and perspective, there exhibited: how is the mind agitated and bewildered, at being thus, as it were, placed on the borders of a new world! On the first view of such an amazing display of the wisdom and power of the supreme author of nature, the mind for a moment seems suspended, and impressed with awe.

THIS isthmus being the common avenue or road of Indian travellers, we pitched our camp at a small distance from it, on a rising knoll near the verge of the savanna, under some spreading Live Oaks: this situation was open and airy, and gave us an unbounded prospect over the adjacent plains. Dewy evening now comes on, the animating breezes, which cooled and tempered the meridian hours of this sultry season, now gently cease; the glorious sovereign of day, calling in his bright beaming emanations, leaves us in his absence to the milder government and protection of the silver queen of night, attended by millions of brilliant luminaries. The thundering alligator has ended his horrifying roar; the silver plumed ganet and stork, the sage and solitary pelican of the wilderness, have already retired to their silent nocturnal habitations, in the neighbouring forests; the sonorous savanna crane, in well disciplined squadrons, now rising from the earth, mount aloft in spiral circles, far above the dense atmosphere of the humid plain; they again view the glorious sun, and the light of day still gleaming on their polished feathers, they sing their evening hymn, then in a strait line majestically descend, and alight on the towering Palms or lofty Pines, their secure and peaceful lodging places. All around being still and silent, we repair to rest.

SOON after sun-rise, a party of Indians on horseback, appeared upon the savanna, to collect together several herds of cattle which they drove along near our camp, towards the town. One of the party came up and informed us the cattle belonged to the chief of Cuscowilla, that he had ordered some of the best steers of his droves to be slaughtered for a general feast for the whole town, in compliment of our arrival, and pacific negotiations.

THE cattle were as large and fat as those of the rich grazing pastures of Moyomensing in Pennsylvania. The Indians drove off the lowing herds, and we soon followed them to town, in order to be at council at the appointed hours, leaving two young men of our party to protect our camp.

UPON our arrival we repaired to the public square or council-house, where the chiefs and senators were already convened, the warriors and young men assembled soon after, the business being transacted in public. As it was no more than a ratification of the late treaty of St. Augustine, with some particular commercial stipulations, with respect to the citizens of Alachua, the negociations soon terminated to the satisfaction of both parties.

THE banquet succeeds; the ribs and choisest fat pieces of the bullocks, excellently well barbecued, are brought into the apartment of the public square, constructed and appointed for feasting; bowls and kettles of stewed flesh and broth are brought in for the next course, and with it a very singular dish, the traders call it tripe soup; it is made of the belly or paunch of the beef, not overcleansed of its contents, cut and minced pretty fine, and then made into a thin soup, seasoned well with salt and aromatic herbs; but the seasoning not quite strong enough to extinguish its original savour and scent. This dish is greatly esteemed by the Indians, but is, in my judgment, the least agreeable they have amongst them.

THE town of Cuscowilla, which is the capital of the Alachua tribe contains about thirty habitations, each of which consists of two houses nearly the same size, about thirty feet in length, twelve feet wide, and about the same in height; the door is placed midway on one side or in the front; this house is divided equally, across, into two apartments, one of which is the cook room and common hall, and the other their lodging room. The other house is nearly of the same dimensions, standing about twenty yards from the dwelling house, its end fronting the door; this building is two stories high, and constructed in a different manner, it is divided transversely, as the other, but the end next the dwelling house is open on three sides, supported by posts or pillars, it has an open loft or platform, the ascent to which, is by a portable stairs or ladder; this is a pleasant, cool, airy situation, and here the master or chief of the family, retires to repose in the hot seasons, and receives his guests or visitors: the other half of this building is closed on all sides by notched logs; the lowest or ground part is a potato house, and the upper story over it a granary for corn and other provisions. Their houses are constructed of a kind of frame; in the first place, strong corner pillars are fixed in the ground, with others somewhat less, ranging on a line between; these are strengthened by cross pieces of timber, and the whole with the roof is covered close with the bark of the Cypress tree. This dwelling stands near the middle of a square yard, encompassed by a low bank, formed with the earth taken out of the yard, which is always carefully swept. Their towns are clean, the inhabitants being particular in laying their filth at a proper distance from their dwellings, which undoubtedly contributes to the healthiness of their habitations.

THE town stands on the most pleasant situation, that could be well imagined or desired, in an inland country; upon a high swelling ridge of sand hills, within three or four hundred yards of a large and beautiful lake, the circular shore of which continually washes a sandy beach, under a moderately high sloping bank, terminated on one side by extensive forests, consisting of Orange groves, overtopped with grand Magnolias, Palms, Poplar, Tilia, Live Oaks and others already noticed; and the opposite point of the crescent, gradually retires with hommocky projecting points, indenting the grassy marshes, and lastly terminates in infinite green plains and meadows, united with the skies and waters of the lake; such a natural landscape, such a rural scene, is not to be imitated by the united ingenuity and labour of man. At present the ground betwixt the town and the lake is adorned by an open grove of very tall Pine trees, which standing at a considerable distance from each other, admit a delightful prospect of the sparkling waters. The lake abounds with various excellent fish and wild fowl; there are incredible numbers of the latter, especially in the winter season, when they arrive here from the North to winter.

THE Indians abdicated the ancient Alachua town on the borders of the savanna, and built here, calling the new town Cuscowilla; their reasons for removing their habitation were on account of its unhealthiness, occasioned, as they say, by the stench of the putrid fish and reptiles in the summer and autumn, driven on shore by the alligators, and the exhalations from marshes of the savanna, together with the persecution of the musquitoes.

THEY plant but little here about the town, only a small garden spot at each habitation, consisting of a little Corn, Beans, Tobacco Citruls, &c. their plantations which supply them with the chief of their vegetable provisions, such as Zea, Convolvulus batata, Cucurbita citrulus, Cuc. laginaria, Cuc. pepo, Cuc. melopepo, Cuc. verrucosa, Dolichos varieties, &c. lies on the rich prolific lands bordering on the great Alachua savanna, about two miles distance, which plantation is one common inclosure, and is worked and tended by the whole community; yet every family has its particular part, according to its own appointment, marked off when planted, and this portion receives the common labour and assistance until ripe, when each family gathers and deposits in its granary its own proper share, setting apart a small gift or contribution for the public granary, which stands in the centre of the plantation.

THE youth, under the supervisal of some of their ancient people, are daily stationed in their fields, who are continually whooping and hallooing, to chase away crows, jackdaws, black-birds and such predatory animals, and the lads are armed with bows and arrows, who, being trained up to it from their early youth, are sure at a mark, and in the course of the day load themselves with squirrels, birds, &c. The men in turn patrole the Corn fields at night, to protect their provisions from the depredations of night rovers, as bears, raccoons and deer; the two former being immoderately fond of young Corn, when the grain is filled with a rich milk, as sweet and nourishing as cream, and the deer are as fond of the Potatoe vines.

AFTER the feast was over, we returned to our encampment on the great savanna, towards the evening. Our companions, whom we left at the camp, were impatient for our return, having been out horse hunting in the plains and groves during our absence. They soon left us, on a visit to the town, having there some female friends, with whom they were anxious to renew their acquaintance. The Siminole girls are by no means destitute of charms to please the rougher sex: the white traders, are fully sensible how greatly it is for their advantage to gain their affections and friendship in matters of trade and commerce; and if their love and esteem for each other is sincere, and upon principles of reciprocity, there are but few instances of their neglecting or betraying the interests and views of their temporary husbands; they labour and watch constantly to promote their private interests, and detect and prevent any plots or evil designs which may threaten their persons, or operate against their trade or business.

IN the cool of the evening I embraced the opportunity of making a solitary excursion round the adjacent lawns: taking my fuzee with me, I soon came up to a little clump of shrubs, upon a swelling green knoll, where I observed several large snakes entwined together; I stepped up near them, they appeared to be innocent and peaceable, having no inclination to strike at any thing, though I endeavoured to irritate them, in order to discover their disposition, nor were they anxious to escape from me. This snake is about four feet in length and as thick as a man’s wrist; the upper side of a dirty, ash colour; the squamae large, ridged and pointed; the belly or under side of a reddish, dull flesh colour; the tail part not long but slender like most other innocent snakes. They prey on rats, land frogs, young rabbits, birds, &c. I left them, continuing my progress and researches, delighted with the ample prospects around and over the savanna.

STOPPING again at a natural shrubbery, when turning my eyes to some flowering shrubs, I observed near my feet, the surprising glass snake (anguis fragilis;) they seem as innocent and harmless as worms. They are, when full grown, two feet and an half in length, and three fourths of an inch in thickness; the abdomen or body part is remarkably short, and they seem to be all tail, which, though long, gradually attenuates to its extremity, yet not small and slender as in switch snakes; the colour and texture of the whole animal is so exactly like bluish green glass, which, together with its fragility, almost persuades a stranger that they are in reality of that brittle substance: but it is only the tail part that breaks off, which it does like glass, by a very gentle stroke from a slender switch. Tho’ they are quick and nimble in twisting about, yet they cannot run fast from one, but quickly secrete themselves at the bottom of the grass or under leaves. It is a vulgar fable, that they are able to repair themselves after being broke into several pieces; which pieces, common report says, by a power or faculty in the animal, voluntarily approach each other, join and heal again. The sun now low, shoots the pointed shadows of the projecting promontories far on the skirts of the lucid green plain, flocks of turkeys calling upon their strolling associates, circumspectly march onward to the groves and high forests, their nocturnal retreats. Dewy eve now arrived; I turned about and regained our encampment in good time.

THE morning cool and pleasant, and the skies serene, we decamped, pursuing our progress round the Alachua savanna. Three of our companions separating from us, went a-head and we soon lost sight of them: they again parting on different excursions, in quest of game and in search of their horses; some enter the surrounding groves and forests, others strike off into the green plains. My companion, the old trader and myself kept together, he being the most intelligent and willing to oblige me; we coasted the green verge of the plain, under the surrounding hills, occasionally penetrating and crossing the projecting promontories, as the pathway or conveniency dictated, to avoid the waters and mud which still continued deep and boggy near the steep hills, in springy places; so that when we came to such places, we found it convenient to ascend and coast round the sides of the hills, or strike out a little into the savanna, to a moderately swelling ridge, where the ground being dry, and a delightful green turf, was pleasant travelling; but then we were under the necessity to ford creeks or rivulets, which are the conduits or drains of the shallow, boggy ponds or morasses just under the hills; this range or chain of morasses continues round the South and South-West border of the savanna, and appeared to me to be fed or occasioned by the great wet bay gale or savanna Pine lands, which lay immediately back of the high, hilly forests on the great savanna, part of which we crossed in coming from Cuscowilla, which bottom is a flat, level, hard sand, lying between the sand ridge of Cuscowilla and these eminences of the great savanna, and is a vast receptacle or reservoir of the rain waters, which being defended from the active and powerful exhalations of the meridian sun, by the shadow of the Pine trees, low shrubs and grass, gradually filtering through the sand, drain through these hills and present themselves in innumerable little meandering rills, at the bases of the shady heights fronting the savanna.

OUR progress this day was extremely pleasant, over the green turf, having in view numerous herds of cattle and deer, and squadrons of horse, peaceably browzing on the tender, sweet grass, or strolling through the cool fragrant groves on the surrounding heights.

BESIDES the continued Orange groves, these heights abound with Palms, Magnolias, Red Bays, Liquid-amber, and Fagus sylvatica of incredible magnitude, their trunks imitating the shafts of vast columns: we observed Cassine, Prunus, Vitis labrusca, Rhamnus volubilis, and delightful groves of Æsculus pavia, Prunus Caroliniana, a most beautiful evergreen, decorated with its racemes of sweet, white blossoms.

PASSING through a great extent of ancient Indian fields, now grown over with forests of stately trees, Orange groves and luxuriant herbage. The old trader, my associate, informed me it was the ancient Alachua, the capital of that famous and powerful tribe, who peopled the hills surrounding the savanna, when, in days of old, they could assemble by thousands at ball play and other juvenile diversions and athletic exercises, over those, then, happy fields and green plains; and there is no reason to doubt of his account being true, as almost every step we take over those fertile heights, discovers remains and traces of ancient human habitations and cultivation. It is the most elevated eminence upon the savanna, and here the hills descend gradually to the savanna, by a range of gentle, grassy banks. Arriving at a swelling green knoll, at some distance in the plains, near the banks of a pond, opposite the old Alachua town, the place appointed for our meeting again together; it being near night our associates soon after joined us, where we lodged. Early next morning we continued our tour; one division of our company directing their course across the plains to the North coast: my old companion, with myself in company, continued our former rout, coasting the savanna W. and N. W. and by agreement we were all to meet again at night, at the E. end of the savanna.

WE continued some miles crossing over, from promontory to promontory, the most enchanting green coves and vistas, scolloping and indenting the high coasts of the vast plain. Observing a company of wolves (lupus niger) under a few trees, about a quarter of a mile from shore, we rode up towards them, they observing our approach, sitting on their hinder parts until we came nearly within shot of them, when they trotted off towards the forests, but stopped again and looked at us, at about two hundred yards distance; we then whooped, and made a feint to pursue them, when they seperated from each other, some stretching off into the plains and others seeking covert in the groves on shore; when we got to the trees we observed they had been feeding on the carcase of a horse. The wolves of Florida are larger than a dog, and are perfectly black, except the females, which have a white spot on the breast, but they are not so large as the wolves of Canada and Pennsylvania, which are of a yellowish brown colour. There were a number of vultures on the trees over the carcase, who, as soon as the wolves ran off, immediately settled down upon it; they were however held in restraint and subordination by the bald eagle (falco leucocephalus.)

ON our rout near a long projected point of the coast, we observed a large flock of turkeys; at our approach they hastened to the groves; we soon gained the promontory; on the ascending hills were vestiges of an ancient Indian town, now overshadowed with groves of the Orange, loaded with both green and ripe fruit, and embellished with their fragrant bloom, gratifying the taste, the sight and the smell at the same instant. Leaving this delightful retreat, we soon came to the verge of the groves, when presented to view, a vast verdant bay of the savanna; we discovered a herd of deer feeding at a small distance, upon the sight of us they ran off, taking shelter in the groves on the opposite point or cape of this spacious meadow. My companions being old expert hunters, quickly concerted a plan for their destruction; one of our company immediately struck off, obliquely crossing the meadow for the opposite groves, in order to intercept them, is they should continue their course up the forest, to the main; and we crossed strait over to the point, if possible to keep them in sight, and watch their motions, knowing that they would make a stand thereabouts, before they would attempt their last escape: on drawing near the point, we slackened our gate, and cautiously entered the groves, when we beheld them thoughtless and secure, flouncing in a sparkling pond, in a green meadow or cove beyond the point; some were lying down on their sides in the cool waters, whilst others were prancing like young kids; the young bucks in playsome sport, with their sharp horns hooking and spurring the others, urging them to splash the water.

I ENDEAVOURED to plead for their lives, but my old friend though he was a sensible, rational and good sort of man, would not yield to my philosophy; he requested me to mind our horses, while he made his approaches, cautiously gaining ground on them, from tree to tree, when they all suddenly sprang up and herded together; a princely buck who headed the party, whistled and bounded off, his retinue followed, but unfortunately for their chief, he led them with prodigious speed out towards the savanna very near us, and when passing by, the lucky old hunter fired and laid him prostrate upon the green turf, but a few yards from us; his affrighted followers at the instant, sprang off in every direction, streaming away like meteors or phantoms, and we quickly lost sight of them: he opened his body, took out the entrails and placed the carcase in the fork of a tree, casting his frock or hunting shirt over to protect it from the vultures and crows, who follow the hunter as regularly as his own shade.

OUR companions soon arrived, we set forward again, enjoying the like scenes we had already past; observed parties of Siminole horses coursing over the plains, and frequently saw deer, turkeys and wolves, but they knew their safety here, keeping far enough out of our reach. The wary, sharp sighted crane, circumspectly observing our progress. We saw a female of them sitting on her nest, and the male, her mate, watchfully traversing backwards and forwards, at a small distance; they suffered us to approach near them before they arose, when they spread their wings, running and tipping the ground with their feet some time, and then mounted aloft, soaring round and round over the nest; they set upon only two eggs at a time, which are very large, long and pointed at one end, of a pale ash colour, powdered or speckled with brown. The manner of forming their nests and setting is very singular; choosing a tussock and there forming a rude heap of dry grass, or such like materials, near as high as their body is from the ground, when standing upon their feet; on the summit of this they form the nest of fine soft dry grass, when she covers her eggs to hatch them, she stands over them, bearing her body and wings over the eggs.

WE again came up to a long projecting point of the high forests, beyond which opened to view an extensive grassy cove of the savanna, several miles in circuit; we crossed strait over from this promontory to the opposite coast, and on the way were constrained to wade a mile or more through the water, though at a little distance from us it appeared as a delightful meadow, the grass growing through the water, the middle of which, however, when we came up, proved to be a large space of clear water almost deep enough to swim our horses; it being a large branch of the main creek which drains the savanna; after getting through this morass, we arrived on a delightful, level, green meadow as usual, which continued about a mile, when we reached the firm land; and then gradually ascending, we alighted on a hard sandy beach, which exhibited evident signs of being washed by the waves of the savanna, when in the winter season it is all under water, and then presents the appearance of a large lake. The coast here is much lower than the opposite side, which we had left behind us, and rises from the meadows with a gradual sloping ascent, covered scatteringly with low spreading Live Oaks, short Palms, Zanthoxilon, Laurus Borbonia, Cassine, Sideroxilon, Quercus nigra, Q. sinuata and others; all leaning from the bleak winds that oppress them. About one hundred yards back of this beach, the sand hills gradually rise, and the open Pine forests appear; we coasted a mile or two along the beach, then doubled a promontory of high forests, and soon after came to a swift running brook of clear water, rolling over gravel and white sand, which being brought along with it, in its descent down the steeper sandy beach, formed an easy swelling bank or bar; the waters spread greatly at this place, exhibiting a shallow glittering sheet of clear water, but just sufficient continually to cover the clear gravelly bed, and seemed to be sunk a little below the common surface of the beach; this stream however is soon separated into a number of rivulets, by small sandy and gravelly ridges, and the waters are finally stole away from the sight, by a charming green meadow, which, again secretly uniting under the tall grass, forms a little creek, meandering through the turfy plain, marking its course by reeds and rushes, which spring up from its banks, joining the main creek that runs through the savanna, and at length delivers the water into the Great Sink. Proceeding about a mile farther we came up to, and crossed another brook larger than the former, which exhibited the like delightful appearance. We next passed over a level green lawn, a cove of the savanna, and arrived at a hilly grove. We alighted in a pleasant vista, turning our horses to graze while we amused ourselves with exploring the borders of the Great Sink. In this place a group of rocky hills almost surround a large bason, which is the general receptacle of the water, draining from every part of the vast savanna, by lateral conduits, winding about, and one after another joining the main creek or general conductor, which at length delivers them into this sink; where they descend by slow degrees, through rocky caverns, into the bowels of the earth, whence they are carried by secret subterraneous channels into other receptacles and basons.

WE ascended a collection of eminences, covered with dark groves, which is one point of the crescent that partly encircles the sink or bason, open only on the side next the savanna, where it is joined to the great channel or general conductor of the waters; from this point over to the opposite point of the crescent (which is a similar high rocky promontory) is about one hundred yards, forming a vast semicircular cove or bason, the hills encircling it rising very steep fifty or sixty feet, high, rocky, perpendicular and bare of earth next the waters of the bason. These hills, from the top of the perpendicular, fluted, excavated, walls of rocks, slant off moderately up to their summits, and are covered with a very fertile, loose, black earth, which nourishes and supports a dark grove of very large trees, varieties of shrubs and herbacious plants. These high forest trees surrounding the bason, by their great height and spread, so effectually shade the waters, that coming suddenly from the open plains, we seem at once shut up in darkness, and the waters appear black, yet are clear; when we ascend the top of the hills, we perceive the ground to be uneven, by round swelling points and corresponding hollows, overspread with gloomy shade, occasioned by the tall and spreading trees, such as Live Oak, Morus rubra, Zanthoxilon, Sapindus, Liquid-amber, Tilia, Laurus Borbonia, Quercus dentata, Juglans cinerea, and others, together with Orange trees of remarkable magnitude and very fruitful. But that which is most singular and to me unaccountable, is the infundibuliform cavities, even on the top of these high hills, some twenty, thirty and forty yards across, at their superficial rims exactly circular, as if struck with a compass, sloping gradually inwards to a point at bottom, forming an inverted cone, or like the upper wide part of a funnel; the perpendicular depth of them from the common surface is various, some descending twenty feet deep, others almost to the bed of rocks, which forms the foundation or nucleus of the hills, and indeed of the whole country of East Florida; some of them seem to be nearly filled up with earth, swept in from the common surface, but retain the same uniformity; though sometimes so close together as to be broken one into another. But as I shall have occasion to speak further of these sinks in the earth hereafter, I turn my observation to other objects in view round about me. In and about the Great Sink, are to be seen incredible numbers of crocodiles, some of which are of an enormous size, and view the passenger with incredible impudence and avidity; and at this time they are so abundant, that, if permitted by them, I could walk over any part of the bason and the river upon their heads, which slowly float and turn about like knotty chuncks or logs of wood, except when they plunge or shoot forward to beat off their associates, pressing too close to each other, or taking up fish, which continually croud in upon them from the river and creeks, draining from the savanna, especially the great trout, mudfish, catfish and the various species of bream; the gar are rather too hard for their jaws and rough for their throats, especially here where they have a superfluous plenty and variety of those that are every way preferable; besides the gar being like themselves, a warlike voracious creature, they seem to be in league or confederacy together, to enslave and devour the numerous defenceless tribes.

IT is astonishing and incredible, perhaps, I may say, to relate what unspeakable numbers of fish repair to this fatal fountain or receptacle, during the latter summer season and autumn, when the powerful sunbeams have evaporated the waters off the savanna, where those who are so fortunate as to effect a retreat into the conductor, and escape the devouring jaws of the fearful alligator and armed gar, descend into the earth, through the wells and cavities or vast perforations of the rocks, and from thence are conducted and carried away, by secret subterranean conduits and gloomy vaults, to other distant lakes and rivers; and it does not appear improbable, but that in some future day this vast savanna or lake of waters, in the winter season will be discovered to be in a great measure filled with its finny inhabitants, who are strangers or adventurers, from other lakes, ponds and rivers, by subterraneous rivulets and communications to this rocky, dark door or outlet, whence they ascend to its surface, spread over and people the winter lake, where they breed, increase and continue as long as it is under water, or during pleasure, for they are at all seasons to be seen ascending and descending through the rocks; but towards the autumn, when the waters have almost left the plains, they then croud to the sink in such multitudes, as at times to be seen pressing on in great banks into the bason, being urged by pursuing bands of alligators and gar, and when entering the great bason or sink, are suddenly fallen upon by another army of the same devouring enemy, lying in wait for them; thousands are driven on shore, where they perish and rot in banks, which was evident at the time I was there, the stench being intollerable, although then early in the summer. There are three great doors or vent holes through the rocks in the sink, two near the centre and the other one near the rim, much higher up than the other two, which was conspicuous through the clear water. The beds of rocks lay in horizontal thick strata or laminae, one over the other, where the sink-holes or outlets are. These rocks are perforated by perpendicular wells or tubes, four, five and six feet in diameter, exactly circular as the tube of a cannon or walled well; many of these are broken into one another, forming a great ragged orifice, appearing fluted by alternate jambs and semicircular perpendicular niches or excavations.

HAVING satisfied my curiosity in viewing this extraordinary place and very wonderful work of nature, we repaired to our resting place, where we found our horses and mounted again. One of the company parting from us for the buck that we had shot and left in the fork of the tree. My friend, the old trader, led the shortest way across the plain, after repassing the wet morass which had almost swam our horses in the morning. At evening we arrived at the place of our destination, where our associates soon after rejoined us with some Indians, who were merry, agreeable guests as long as they staid; they were in full dress and painted, but before dark they mounted their horses, which were of the true Siminole breed, set spurs to them, uttering all at once a shrill whoop, and went off for Cuscowilla.

THOUGH the horned cattle and horses bred in these meadows are large, sleek, sprightly and as fat as can be in general, yet they are subject to mortal diseases. I observed several of them dreadfully mortified, their thighs and haunches ulcerated, raw and bleeding, which, like a mortification or slow cancer, at length puts an end to their miserable existence. The traders and Indians call this disease the water-rot or scald, and say it is occasioned by the warm waters of the savanna, during the heats of summer and autumn, when these creatures wade deep to feed on the water-grass, which they are immoderately fond of; whereas the cattle which only feed and range in the high forests and Pine savannas are clear of this disorder. A sacrifice to intemperance and luxury.

WE had heavy rains during the night, and though very warm yet no thunder and very little wind. It cleared away in the morning and the day very pleasant. Sat off for the East end of the savanna, collecting by the way and driving before us, parties of horse, the property of the traders; and next morning sat off on our return to the lower store on St. John’s, coasting the savanna yet a few miles, in expectation of finding the remainder of their horses, though disappointed.

WE at last bid adieu to the magnificent plains of Alachua, entered the Pine forests, and soon fell into the old Spanish highway, from St. Augustine across the isthmus of Florida, to St. Mark’s in the bay of Apalache. Its course and distance from E. to W. is, from St. Augustine to Fort Picolata on the river St. Juan, twenty-seven miles; thence across the river to the Poopoa Fort, three miles; thence to the Alachua Savanna, forty-five miles; thence to Talahasochte on the river Little St. Juan, seventy-five miles; thence down this river to St. Mark’s, thirty miles; the whole distance from St. Augustine to St. Mark’s, one hundred and eighty miles. But that road having been unfrequented for many years past, since the Creeks subdued the remnant tribes of the ancient Floridans, and drove the Spaniards from their settlements in East Florida into St. Augustine, which effectually cut off their communication between that garrison and St. Mark’s; this ancient highway is grown up in many places with trees and shrubs, but yet has left so deep a track on the surface of the earth, that it may be traced for ages yet to come.

LEAVING the highway on our left hand, we ascend a sandy ridge, thinly planted by nature with stately Pines and Oaks, of the latter genera, particularly Q. sinuata, S. flamule, Q. nigra, Q. rubra. Passed by an Indian village situated on this high, airy sand ridge, consisting of four or five habitations; none of the people were at home, they were out at their hunting camps; we observed plenty of corn in their cribs. Following a hunting path eight or nine miles, through a vast Pine forest and grassy savanna, well timbered, the ground covered with a charming carpet of various flowering plants, came to a large creek of excellent water, and here we found the encampment of the Indians, the inhabitants of the little town we had passed; we saw their women and children, the men being out hunting. The women presented themselves to our view as we came up, at the door of their tents, veiled in their mantle, modestly shewing their faces when we saluted them. Towards the evening we fell into the old trading path, and before night came to camp at the Halfway Pond. Next morning, after collecting together the horses, some of which had strolled away at a great distance, we pursued our journey and in the evening arrived at the trading house on St. Juan’s, from a successful and pleasant tour.