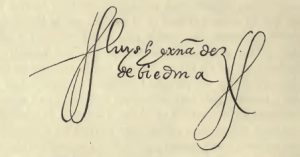

Biedma’s is the only complete account whose original document survives, and is personally signed by Biedma.

The final account is that of Hernandez de Biedma, the factor of the De Soto expedition and follows the expedition from Arkansas to Texas and then back again. His account is the most brief as well as the only holograph manuscript written by an eyewitness. The original report, twenty folios in length, was titled flatly “Account of the events of the journey of Captain Soto and the character of the land.” Biedma’s account was written relatively impartially, as he omits any direct opinion, unlike the previous excerpts, as he simply tells the facts, describes the natives, conflicts, and travel time. Biedma’s focus was not to condemn the Natives or De Soto but rather to report back to the King what had occurred. This excerpt is taken from the end of the account and will wrap up the De Soto expedition by recounting how the troops escaped La Florida on the Mississippi River after De Soto’s death.

Edited by Amelia Zimmerman, University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Suggested Reading

Galloway, Patricia (ed.). The Hernando De Soto Expedition. U Nebraska P, 1997.

Clayton, Lawrence A., Vernon J. Knight, and Edward C. Moore (eds.). The De Soto Chronicles: the Expedition of Hernando De Soto to North America in 1539-1543. Tuscaloosa: U Alabama P, 1995. Print.

Luys Hernández de Biedma. “Relacíon de la Isla de Florida.” Transl. John E. Worth. In The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernandeo de Soto to North America, 1539-1543. Tuscaloosa: U Alabama P, 1993.

…. We turned again to where the Indians guided us and we went to some scattered villages that were called Tatilcoya. Here we found a large river, and afterward we saw that it flowed into the great river [the Mississippi]. We had information that on this river upstream was a great province called Cayas. We went to it and found that it was all scattered population, though heavy, and several excursions were made. The land is very rugged with mountains. An excursion was made in which the cacique and many people were apprehended. When we asked for news of the land, they told us that if we went upriver, we would come upon a well-provisioned province that was called Tula. The governor wished to go see if it was a place where the people could winter, and he went with twenty on horseback. He left all the rest in this province of Cayas.

Before arriving at the province of Tula, we crossed some rugged mountains and arrived at the town without their having heard anything of us. We began to apprehend some Indians, and they began to call to arms and make war on us. They wounded that day nine or ten horses and seven or eight Spaniards, and such was their ferocity that they joined together, eight by eight and ten by ten, and came at us like wounded dogs. We killed about thirty or forty Indians. It seemed to the Governor that it was not good to halt there that night, because he led very few people, and he returned by the road on which we had come to a clearing in a lowland that the river made, having crossed a bad pass of the mountain range because there was fear that the Indians might take us at that pass.

The next day he arrived where his people were, and there were none of those Indians we had brought, nor did he find in that province Indians who could understand the  interpreter. He commanded that all should prepare to travel to that province [of Tula]. We then went there. The day after we arrived, three very large squadrons of Indians came upon us at dawn, on three sides. We came forth to them and routed them and did them some damage, as a result of which they attacked us no more.

interpreter. He commanded that all should prepare to travel to that province [of Tula]. We then went there. The day after we arrived, three very large squadrons of Indians came upon us at dawn, on three sides. We came forth to them and routed them and did them some damage, as a result of which they attacked us no more.

After two or three days, they sent the messengers as if in peace. Although we did not understand one thing for lack of the interpreter, through signs we told them that they should bring us interpreters for those [Indians] behind us, and they brought us five or six Indians who understood the interpreters that we brought. They asked us what people we were and what we were looking for. We asked them about some large provinces where there would be much food, because already the cold of the winter was greatly menacing us. They told us that the way that we were going, they knew of not one large village. They pointed out to us that if we wanted to turn east and southeast or northwest we would find large villages.

Having seen that we did not have any other choice, we turned again southeast and went to a province called Quipana, which is at the foot of some very rugged mountains, and here we went east and traversed these mountains and descended to some plains, where we found a village suited for our purpose, because there was a town nearby that had much food, and it was on a large river that ended at the great river by which we left. This province was called Viranque.

Here we spent the winter. There were such great snows and cold weather that we thought we were dead men. In this town died the Christian who had been one of Narváez’s men, whom we had found in the land and taken along as interpreter. We left from here at the beginning of March, since it appeared to us that the fury of the cold weather had abated, and we traveled downstream along that river, where we found other well-populated provinces with a quantity of supplies, until we arrived at a province that seemed to us to be one of the best that we had come upon in all the land, which is called Anicoyanque. Here another cacique, who was named Guachoyanque, came to us in peace. He has his village on the large river and wages much war with this other [province] where we were. The Governor departed then for this other town of Guachoyanque and took the cacique with him. It was a good town, well palisaded and strong. It had little food, because the Indians had hidden it all.

Here the Governor was already determined, if he were to find the sea, to make brigantines in order to send word to Cuba that we were alive, so that they might provide us with some horses and the things that we had need of. He sent the captain south to see if he could discover some road to go to look for the sea, because from the account of the Indians nothing could be found out about what there might be, and he returned saying that he did not find a road nor a way to cross the large swamps along the great river. The Governor, from seeing himself cut off and seeing that not one thing could be done according to his purpose, was afflicted with sickness and died.

The Governor dead, he left Luis de Moscoso appointed as Governor. We decided that since we could not find a road to the sea, we should head west, and that it could be that we might be able to get out by land to Mexico, if we did not find anything else in the land or any place to halt. We walked seventeen days’ journey until we arrived at a province of Chavete, where the Indians made much salt; we did not find out anything about the west. From here we went to another province that is called Aguacay. We spent another three days’ journey getting there, still going straight west. From here the Indians told us that we could not find more villages, but rather that we should descend southwest and south, because there we would find villages and food, and that going the way that we asked about there were some great stretches of sand [arenales grandes], and neither villages nor any food.

We had to return where the Indians guided us, and we went to a province that is called Nisione, and another that is called Nandacao, and another that is called Lacame, and across land more and more sterile and with less food. We went along asking about a province that they told us was large, which was called Xuacatino. This cacique of Nandacao gave us an Indian to guide us, with the intent of placing us where we could never get out, and so he guided us across rugged land and off road, until finally he told us that he no longer knew where he was leading us, and that his lord had commanded him to lead us where we would die of hunger.

We took another guide who led us to a province that is called Hais, where cows are in the habit of gathering at times, and as the Indians saw us enter through their land, they began to cry out that they should kill the cows that were coming; they came forth to shoot arrows at us and did us some damage. We departed from here and arrived at the province of Xacatin, which was among some dense forests and lacked food. From here the Indians guided us east to other towns, which were small and had little food, saying that they were leading us to where there were other Christians like us. It seemed afterward to be a lie and that they could not have news of any others but us; since we had made so many turns [legs?], in some of these they must have heard of our passing.

We turned south again, with purpose of living or dying or traversing to New Spain, and we walked about six days’ journey south and southwest. There we halted and sent ten men on swift horses to travel eight or nine days, or as many as they were able, to see if they could find some town in order to replenish the corn so we could continue on our way, and they traveled as far as they could and came upon some poor people who did not have houses, but rather some miserable little settlements where they situated themselves, and they neither sowed nor gathered anything but rather maintained themselves only on fish and meat.

They brought three or four of these Indians, we found no one who could understand the interpreter. Having seen that we had lost the interpreter and that we found nothing to eat, that we were now lacking the corn that we had carried on our backs, and that it was [impossible] for so many people to traverse so miserable a land, we decided to return to the town where Governor Soto had died, because there it seemed to us that it was possible to fashion vessels to leave the land. We returned along that same road that we had followed until we arrived at the town where the Governor had died.

Having arrived here, we did not find as good provisions as we thought, because we did not find food in the town, since the Indians had hidden it. We had to look for another town in order to be able to winter and fashion the ships. Thank God we discovered two towns much to our purpose that were on the great river and had a great quantity of corn and were palisaded, and there we halted and built our ships with much labor. We made seven brigantines and spent six months in finishing them. We cast off the brigantines in the river, and it was a thing of mystery that even though they were caulked only with the bark of those mulberry trees and without any pitch, we found them watertight and very good. We towed some canoes downriver with us in which we carried twenty-six horses, so that if at the seacoast we should find some village that could sustain us with food, from there we would send a pair of brigantines to give a message to the Viceroy of New Spain, so that he might provide us ships in which we could leave the land.

The second day that we were going downriver, there came forth to us about forty or fifty very large and swift canoes of Indians, among which there was a canoe that carried eighty Indian warriors, and they began to shoot arrows at us and pursue us, shooting more arrows at us. It seemed to some of those in our ships that it was cowardly not to attack them, and they took four or five small canoes of those that we were towing and went toward the canoes of the Indians, who, as soon as they saw them, encircled them as best they could and would not let them leave from among them. They upset the canoes in the water, and thus they killed this day twelve very honorable men, because we could not aid them, since the current of the river was so great and we had few oars in our ships. With this victory, the Indians came following us downriver, until we arrived at the sea, which took nineteen days’ journey. They did us much damage and wounded many people, because since they saw that we did not have arms with which to do them damage from a distance, for we no longer had either arquebus or crossbow but only some swords and shields, they now had lost their fear and drew very near to shoot arrows at us.[1]

We came forth to the sea through the mouth of the river and went across a bay that the river makes, so large that we navigated three days and three nights with reasonable weather, and in all that time we did not see land. It seemed to us that we were far out at sea, and at the end of these three days and three nights we gathered water as fresh as from the river, which was good to drink. We saw some little islets toward the southwest side, and we went to them, and from there we went along the coast, gathering shellfish and looking for things to eat, until we entered the river of Panuco, where we were very well received by the Christians.

[1] The final section of Biedma’s relation is written in a different hand than the bulk of the manuscript, and using different ink than both the text and the signature immediately below, suggesting that this final section was written by a different scribe (and may have been added after the signature, which is overlapped by this final section). It is possible that Biedma originally intended to terminate the relation here, for he mentioned their departure from the river into the sea in the previous sentence. [Worth’s note]